The oppressive summer heat beat down on the dried grass in Baisley Pond Park in the far outer edge of Queens on July 17 as Evie Litwok looked around at assorted tables, chairs, and people milling about. Just a few feet from her, folks were sampling mac & cheese from Just Soul Catering, eating cupcakes from Chef Fresh Antwoin Gutierrez, or listening to Die Jim Crow records. Others were sitting under tents, taking shelter from the heat or filling out voting registration cards. Oppressive as the weather was, the day was filled with music, laughter, and conversation.

“What is it going to take for someone to say, ‘What can I do?’” Litwok asked as she surveyed the scene. “How do we get the LGBT community to care about us? We don’t have money. We can’t get their dollars. We can’t frequent their spots. We live in a different world. And I’m here. We should be their brothers and sisters. So, I know they should care about what happens to so many in their population.”

The “us” Litwok was referring to are the formerly incarcerated, including those like herself who identify as LGBTQ and have been released from prison, only to find little chance of a livelihood on return to society. It’s why she founded the organization Witness to Mass Incarceration in 2016.

No country has a larger prison population than the United States, with around two million people currently incarcerated. A disproportionate number are people of color. Litwok wanted to remind the broader LGBTQ community that beyond ethnicity and race, sexual minorities are also among the incarcerated.

Litwok mentioned statistics from the Williams Institute indicating up to 43% of women prisoners and 10% of men prisoners identify as sexual minorities in some way.

Her experience, she said, brought those numbers alive.

“I went to prison and I saw a whole lot of lesbians,” Litwok said. While LGBTQ issues are portrayed by Laverne Cox, Lea DeLaria, Uzo Adaba, and others in the memoir-based Netflix show “Orange is the New Black,” Litwok added, “I was the only idiot that came out though. Everybody else looks like a stone butch but didn’t come out there,” creating a situation where “they punish me for coming out,” which she detailed in an essay on Medium.

Beyond the personal side, however, Litwok wanted to make clear that “there’s an intersection of the LGBT community with criminal justice that the larger LGBT community just doesn’t pay as much attention to. So many of their people are in jail or they’re sex workers. We need to decriminalize that. We need to not criminalize HIV. So, it was right in front of me. We are a huge target audience, and given the laws that are being passed, we are likely to go to prison more.”

Coming out of prison in 2015 opened Litwok’s eyes in other ways, too. She tried applying for jobs and highlighted her managerial experience and other skills, but received no responses. The lack of opportunities led Litwork to struggle.

“We do hold people too accountable for things from a long time ago,” said Litwok, who added that the issue is also rife among those who had their convictions overturned like she did. “If you really care about giving us a second chance, buying something allows us to pay our rent and if we are paying our rent we are not going to prison.” This thought inspired her to look more closely at how to help the formerly incarcerated with small businesses.

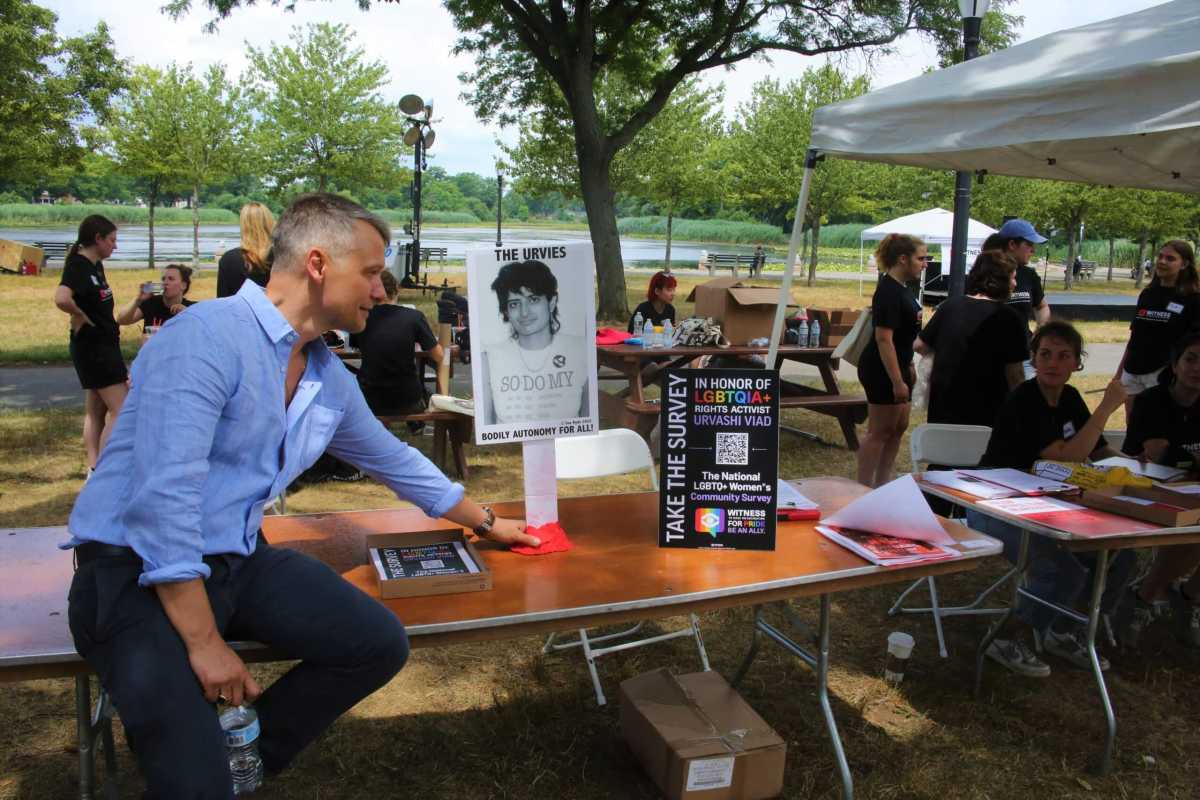

In essence, Litwok is paying forward the kindness she received from an old friend, Urvashi Vaid, the LGBTQ rights activist who died of cancer in May of this year. Vaid found Litwok a low-cost apartment and gave her $1,000 a month to supplement social security and support the creation of the non-profit Witness to Mass Incarceration, for which she is the founder and executive director.

“When I walked into that studio apartment and turned the key, it was the freest, safest I felt in 20 years,” Litwok said.

This led to the creation of the MAP Project, listing businesses owned by the formerly incarcerated. The list now totals about 1,000 businesses, including 110 in New York City. Litwok said they range from cupcake bakers to dress makers to opticians and more. In some ways, the MAP Project acts like a Damron’s or a Green Book, building a community that finds safety through each other, as well as providing a way to support former prisoners with meaningful work and financially viable lives.

“Number one, our greatest enemy is poverty,” she said. “There’s one thing I can tell you with absolute confidence, which is if we have economic stability, we will have no recidivism, period.”

Yet beyond greeting people coming out of prison and creating lists of businesses, Litwok realized she had to connect former prisoners with former prisoners. Still, something else was missing. “The next level of support is the public,” she said. “I needed to launch an outdoor event.”

And thus, Suitcase Sunday was born.

The event’s setup included a stage where LGBTQ acts were part of the entertainment, like Nikki Sweet, a singer and sex-positive activist who is part of VOW, Vibing Over Whorisms. The duo Sandy and Sawyer, known as The Dilators, also performed.

The stage was also the setting for politicians and activists, some of whom had been formerly incarcerated.

Among them included Ceyenne Doroshow, who leads the non-profit Gays and Lesbians Living in a Transgender Society, or GLITS.

“30 days in jail changed my life,” Dorowshow said. “When I got out, I wrote a cookbook. And from that, I began the work of helping my community. One Black trans woman raised millions of dollars independently from communities to buy housing.”

Doroshow added: “When you get out of jail, you often don’t have resources. This is what this is about. Being Black and being trans is hard enough, but being Black and not supported and being an ex-con not supported is really hard. I want you to stand up for this program and stand up for what Evie is doing.”

Doroshow also used her time on stage to point out racial inequity and how those with white privilege could do more. Her words were echoed by others, including Democratic District Leader Melissa Sklarz.

“Evie did her time,” Sklarz said. “She could have walked away, just another white, Jewish lesbian in New York. There are thousands of them. And what she has done is taken her time or essence or energy, to fight for justice for others.”

Sklarz spoke to the audience about her own struggles and said many people might think it is unbelievable that someone like her is where she is today.

“I’m transgender. I transitioned. I was also homeless. I was also a drug addict,” Sklarz said. “And yet, how does a homeless drug addict, who’s white and trans, end up here and in politics when we have thousands and thousands of people struggling with reentry? Reentry is about racism, just like whether it’s health care, just like housing, just like access to food. Reentry is just another aspect to racism in our culture.”

Sklarz went on to remind the audience that “white people manage. They get along. White people always get a second chance. They always get that opportunity. And yet, for people of color, everything is a struggle.” It is for this reason, she said, that “queer people need to stand up. LGBT people need to stand up” to help those re-entering after prison, regardless of orientation or racial background.

After finishing her speech, Sklarz told Gay City News, “Reentry falls onto the fact that people of color struggle to get basic services here in New York. What our LGBT community could do is make more awareness and become, rather than allies, become fighters for anti-racism. I’m here as a white transgender elected official, who was formerly homeless, with substance abuse. And I was able to get back on my feet with the support of a caring community. I hope that people of color that are looking for reentry get the same love and support that I did, when I was able to reenter and become authentic in my life.”

The event’s highest profile political persona was former Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger, a New York liberal icon who lost against Rudy Giuliani in a bid for Mayor in 1997. In her speech, Messinger reflected on the broad inequalities and injustices in New York City, saying, “We are in the richest city in the richest country in the world. We have a society that does almost nothing to keep people out of jail. Almost nothing to work with people in their communities.”

She explained it is difficult “to take off in the business community or in the nonprofit community. And if it’s not easy to do that, it’s triply hard to do that if you have been in prison, and have to carry that with you. And so, the focus now on helping formerly incarcerated persons to start their businesses, run their businesses, do business with each other, and get all of us to give those businesses our business because that’s how you work to turn a society around and add some elements of justice to a criminal injustice system, which is what we’re still saddled with.”

She added it is an “embarrassment to our society that in 2022, we do not have a criminal justice system that deserves the name. The system we have is very good on the criminal side. And very bad on the justice side.”

From the stage, she pointed out the dozens of interns who were part of creating that day’s event, many of them university journalism students. They were tasked with posting short videos on the organization’s Instagram page to highlight former prisoners and their businesses. Messinger also mentioned how Witness to Mass Incarceration owes its existence to “Urvashi Vaid, several of us knew, who was an extraordinary leader in the LGBTI Community.”

After her speech, Messinger told Gay City News, “the worst thing here is that there is a system, it’s just a negative system.” She added that young people receive little guidance when things go wrong to prevent them from entering the prison system, with little “to help them when they leave. So that’s a system designed to create a very high jail population, which is what we have. And I think Evie is precisely the opposite. That she did what she did after she got out and the place she came from.”

Another political supporter of Litwok’s work is New York City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams, represented at the event by Cheryl Watts, her constituent liaison. Watts read a statement calling Witness to Mass Incarceration, “an incredible organization that empowers formerly incarcerated people and gives them life and opportunities to survive. It is vital to support New Yorkers who face tremendous barriers in their lives, particularly women and LGBTQ+ individuals who are returning home from past justice involvement.” She added the organization “is connecting formerly incarcerated people with networks to help meet their needs and build safe, healthy and economically empowered lives.”

The main on-stage tribute to Urvashi Vaid came from Fabrice Houdart, who is also Witness to Incarceration’s board president. Houdart explained that the “reason why we are remembering her today is that Urvashi and the history of Witness to Mass Incarceration interconnect.” He used a story by Masha Gessen in the New Yorker, called “The Prolific Activism of Urvashi Vaid,” which details the 2016 CBST meeting to preface his tribute.

“If it wasn’t for Urvashi, maybe Evie would not have had the courage to start this wonderful organization,” Houdart told the audience, adding that is “the reason why we are marking today as being the Urvashi Suitcase Sunday. Because Urvashi was that kind of person.”

Houdart further explained that a “huge segment” of people who are incarcerated are LGBTQ in large part because many people in the community are living on the margin of society.

“Chances are that you’re going to get your finger caught in the machine of criminal justice in the United States,” Houdart said. “And we all know that in the US, if you get your finger caught, they are going to take the entire arm and the body with it. And so, what I loved about Urvashi was that she paid attention to the communities within the LGBTQ+ community that we’re a part of.”

Though he did not give specific examples, Houdart’s words were a reminder of the many ways in which the LGBTQ community is caught within the system.

These include the late Layleen Xtravaganza Cubilette-Polanco, a trans woman of color who died in solitary confinement on Rikers Island in June 2019 while in need of medical attention, to seemingly 1950’s style sting operations that continued until recently, falsely entrapping gay men in public bathrooms in New York City. Some HIV-positive members of the LGBTQ community, like Michael Johnson, have been jailed for non-disclosure of their status during sexual interactions.

Prison rape is also a major concern for those who identify as LGBTQ. One infamous case was that of adult actor Milan Gamiani who was repeatedly raped after he was jailed for refusing to testify in a trial against a former partner, leading to suicide attempts.

Litwok’s group prepared a report for the Prison Rape Elimination Act Resource Center on the issues for incarcerated LGBTQ people.

Early in her life, Litwok also saw how communities help each other, even after experiencing perhaps the worst possible trauma. She is the American-born daughter of Holocaust survivors — her mother had been in Auschwitz. Raised in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, where thousands of European Jewish refugees resettled during the Holocaust period, she developed a deep understanding of how trauma pervades every aspect of life and that communities must also help each other when no one else will.

“They adopted each other as a huge family,” she said of the displaced community, “and they helped build each other’s businesses in time. So, I remembered how powerfully important it was to help each other.”

For the LGBTQ community, Litwok’s view is that the problem of mass incarceration is too big to ignore, even if other issues, including marriage rights, tend to get the spotlight and are the focus of glamorous galas. “You look at the dollars we get funded, you have to say why is it not such an unimportant issue to a community, where maybe 40% of the women in prison are a sexual minority? How do you not put that together? And how do you not convene panels to know the extent of the problem?”

Looking out at the participants in the Suitcase Sunday program — about 30 of the 60 stalls were used — Litwok estimated about half identified along the LGBTQ spectrum. Importantly, she said, “the formerly incarcerated people who are not LGBT are more supportive of the formerly incarcerated LGBT than the LGBT population is because we have a shared experience. And that shared experience allows us to know how hard it is to rebuild our lives.” She added that “we need especially our white LGBTQ people to come to a space and be willing to support different businesses be willing to buy from different businesses.”

Others pointed out how the bonds among those in the stalls transcended racial and sexual identity, specifically because those differences were used against them in prison. Justine Moore, who goes by the name Taz, was staffing the booth for the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls.

Moore, who identifies as bisexual, spoke of how prisoners are dehumanized by staff. “I think that people are distinguishing LGBTQ, non-conforming, etc, etc, people from men and women. Like they are separating the two instead of looking at them as human beings. So, I think that plays a big part in how the media sees people, that plays a big part, and people not respecting them as humans when they go inside of a prison.” She added that sometimes it comes down to how “they want to be named and carry themselves and their pronouns, people dehumanize them.”

Pointing to themes of intersectionality, Moore had a strong message for those who do not know what it is like to be in prison, asking them to rethink how they view anyone who has been incarcerated, regardless of sexuality and race.

“You have Black people, you have white people, and as people in general, we all know that Black and brown people and poor people are oppressed in this country. LGBTQ people all fall right under that same Black, brown, LGBTQ, poor people. We are all oppressed, and the people of this society and of this government, they love to keep us oppressed and they love to keep our foot their foot on our neck, so we can’t prosper,” she said, giving a vivid visual of often inflicted police brutality as a larger social metaphor.

“I would like people to judge people for who they are, to know people’s struggle and where they came from in order to get to where they are. And know that we are human beings, whether we are LGBTQ, non-conforming, male, female. We are human, and stop trying to dehumanize us.”