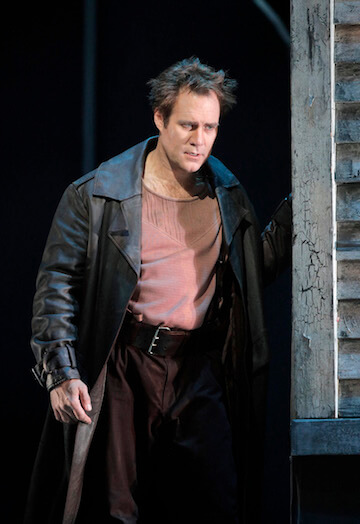

Dimitrij Clay Hilley and Olga Tolkmit were doomed lovers in Antonín DvoÅ™ák’s “Dimitrij,” presented by Bard Summerscape. | CORY WEAVER

The Bard Summerscape 2017 Festival presented Antonín Dvorák’s “Dimitrij,” the plot of which functions as an operatic sequel to Modest Mussorgsky’s “Boris Godunov.” Both operas are set during the early 17th century period of Russia’s “Time of Troubles” when the pretender False Dmitri usurped the czar’s crown from Feodor II, Gudonov’s heir. The final scene of Mussorgsky’s “Boris Gudonov” depicts the False Dmitri marching his troops through the Kromy Forest on his way to Moscow.

The first scene of Dvorák’s “Dimitrij” reveals the pretender Dimitrij arriving in Moscow hoping to be recognized as the true son and heir of Ivan the Terrible by his “mother,” Ivan’s widow dowager Czarina Marfa. Whereas Mussorgsky’s False Dmitri/ Grigori Otrepyev is a patent fraud and political opportunist, Dvorák’s Dimitrij is a nobly misguided political pawn who has been raised from early childhood to believe he really is the czarevich, brought up in secret in a monastery. Married to the Polish Princess Marina Mniszech, Dimitrij becomes the protector and lover of Boris Gudonov’s persecuted daughter Xenia. This ill-fated love affair precipitates a tragic series of events where Marina’s jealousy and the opposition of Prince Shuisky combine to destroy both Dimitrij and Xenia.

Dvorák’s score for “Dimitrij” was revised several times between 1881 and 1895 — it shows the influence of French grand opera but the later revisions brought it more in line with Wagnerian compositional forms. The four-act score is certainly Wagnerian in length; the Bard performance lasted just under four hours. Dvorák’s musical style here does not evoke Mussorgsky — “Boris Godunov” was not known outside Russia at the time — but sounds typically Czech, resembling the serious works of Bedrich Smetana with folk-like sprung rhythms. In common with Russian opera, French grand opera, and Wagnerian music-drama, Dvorák’s score is filled with large choral sections — either somber hymns or warlike marches depending on the situation. The vocal solos are generally declamatory and free form in Wagnerian style. The extended love duets between Dimitrij and Xenia provide the lyrical high points of the score. The opera could use judicious cutting, and several scenes in Marie Cervinková-Riegrová’s libretto are theatrically static, including the entire first act.

Bard Summerscape’s “Dimitrij” shines musically; On Site can’t save “La mère coupable

Anne Bogart’s updated production combined dreary visuals with dramatically abstruse staging that set the action somewhere in Central or Eastern Europe at the end of the 20th century. The ugly unit set by David Zinn consisted of a distressed assembly hall/ gymnasium with blue brick walls and bare wood floors. Painted on the back wall in Cyrillic is the slogan “Victory Begins Here.” This depressing space was unconvincingly adapted into the crypt of Ivan the Terrible, a royal banquet hall, and the czar’s chambers in the Kremlin by extras wheeling in cheap-looking props and furniture. Constance Hoffman’s costumes consisted of ill-fitting jeans and polyester print ensembles for the people of Russia and shabby suits and gowns for the nobility. A little blond boy in denim wandered alone onstage during the prelude and later revealed himself as the ghost of the murdered czarevich presiding over the final tableau.

Musically things were much better. The voices were for the most part strong and powerful if not consistently beautiful. In the title role, Clay Hilley sounded like a Lohengrin in the making, sustaining the long, demanding high declamation with his brightly projected youthful heroic tenor. Hilley is still awkward as an actor, and Bogart’s direction and Hoffman’s costumes did not help him. Melissa Citro as the haughtily cynical Marina had the resting bitch face and contemptuous attitude down cold while modeling Slavic nouveau riche fashions. Her brilliant Wagner-Strauss soprano occasionally took on a hollow quality and cutting edge that actually suited the character. As Xenia, soprano Olga Tolkmit (Electra in Bard’s production of Sergei Taneyev’s “Oresteia”) projected a vibrant house-filling sound that surprisingly emanated from a waif-like frame. A few unsettled tones also proved dramatically suitable to her sensitive portrayal of a desperate girl. I was impressed by the dusky richness of Nora Sourouzian’s mezzo-soprano tone as Marfa and Peixin Chen’s imposing bass as the Patriarch. Baritone Levi Hernandez lacked vocal charisma as Shuisky but sang and acted with energy.

Dr. Leon Botstein excels in this type of densely orchestrated late 19th century/ early 20th century Central European score. He and his strong musical team made a strong case for Dvorák’s highly melodic — if sprawling and dramatically unfocused — historical opera. Critics have asserted that Dvorák lacked the talent for operatic composition. “Rusalka” and, to a lesser degree, “Dimitrij” prove them wrong.

The US premiere presentation on June 20 of Darius Milhaud’s 1966 operatic sequel “La mère coupable” (“The Guilty Mother”) revealed a composer with no idea how to set a vocal line or create theater with music. This was the final installment of On Site Opera’s “Figaro Project,” which previously presented Paisiello’s “Il Barbiere di Siviglia” and Marcos Portugal’s “Il Matrimonio di Figaro.” The French-language libretto of “La mère coupable” was adapted by Milhaud’s wife Madeleine from the final play in Pierre Beaumarchais’ “Figaro” trilogy. This least popular and performed of the three comedies features the same characters from the earlier “Figaro” plays — older but no wiser in dealing with the fallout from their youthful follies and indiscretions.

Jennifer Black and Amy Owens were highpoints in On Site Opera’s earnest effort to salvage Darius Milhaud’s “La mère coupable.” | FAY FOX

Set 20 years after the events in “The Marriage of Figaro” (and also after the French Revolution), the play and opera center on themes of forgiveness and reconciliation. The Count and Countess Almaviva have each had an illegitimate child outside of their marriage — the Countess bore Léon after a brief liaison with Cherubino and the Count’s ward Florestine is the fruit of one of his many extramarital affairs. The Countess is being blackmailed by the Irish blackguard Bégearss, who has stolen a hidden letter revealing her shameful secret. Bégearss, “another Tartuffe,” has hoodwinked the Count into disinheriting Léon and bestowing his diminished fortune on his ward Florestine, whom Bégearss schemes to marry for her inheritance. Florestine loves Léon but fears they may be half-brother and sister. Figaro and Susanna plot to foil Bégearss and set all to rights, reconciling the suspicious Count with the repentant Countess and freeing the young lovers to wed. Beaumarchais’ final “Figaro” play contains less wit and farcical situations than the earlier comedies — the sentimental story concentrates on the personal over the political.

Milhaud’s orchestration is dense, mildly dissonant, and busy. There is not an ounce of lightness or wit in the score — one would never guess from the music alone that this is a comic or tragicomic opera. The churning angst-ridden orchestral noise plods on for over two hours with no variation of mood or color in response to character or situation. Vocal lines consist of accompanied recitative, blustering vocal declamation, or tuneless arioso, with the Countess getting most of the vocal opportunities such as they are.

The singers did what they could with this unrewarding material. The undervalued soprano Jennifer Black sang with rich tone and emotive generosity, giving tragic weight to the Countess’ life of regrets. Mezzo Marie Lenormand sang Suzanne with real French style and verbal acuity. Youthful coloratura Amy Owens was a sunny beam of light in sight and sound as Florestine. Adam Cannedy as the Count, Marcus DeLoach as Figaro, and Matthew Burns as Bégearss worked hard but without success attempting to create characters out of music that lacked character of any kind. Tenor Andrew Owens as Léon created a vivid character onstage but severe allergies reduced him to declaiming his vocal lines without tone or music. I suspect little was lost.

The site-specific performance space On Site Opera chose for Milhaud’s opera was the Garage in Hell’s Kitchen — a large windowless white brick loft space as nondescript and empty as Milhaud’s score. Eric Einhorn’s serviceable modernized production placed the various settings in three corners of the huge open, characterless space with the orchestra placed in the middle (surtitles were awkwardly projected on the side walls causing spectators to constantly look left or right rather than directly at the stage). The scene settings of Cameron Anderson and costumes by Beth Goldenberg stressed the reduced circumstances of the Almaviva family in exile in Paris.

Geoffrey McDonald led the well-prepared International Contemporary Ensemble in an energetic reading of the score. The well-intentioned failure of this enterprise must be blamed on the deceased composer. On Site Opera, as usual, approached the piece thoughtfully, employing gifted performers, but all that talent went to waste.