BY DAVID KENNERLEY | If “Dada Woof Papa Hot” is one of the most cryptic titles of the theater season, it’s also one of the most brilliant.

Peter Parnell’s of-the-moment comic drama, now in previews at the Mitzi Newhouse Theater at Lincoln Center, considers the minefields inherent in becoming new parents, particularly when those parents happen to be a gay male couple.

“Dada Woof Papa Hot” refers to the first four words uttered by the daughter of Alan (John Benjamin Hickey) and Rob (Patrick Breen). Each word is innocuously cute on its own, but strung together, it speaks to the pressing need to reconcile the schism between the couple’s past “gay” lives and their current “parent” lives.

The experience of Alan, who is 50, and Rob, in his mid 40s, is contrasted with that of much younger gay dads, Scott (Stephen Plunkett) and Jason (Alex Hurt).

Can you answer to Dada or Papa (as many gay dads are called by their kids) and still be a self-actualized sexual being? That’s the thorny question that lies at the center of this inspired new work.

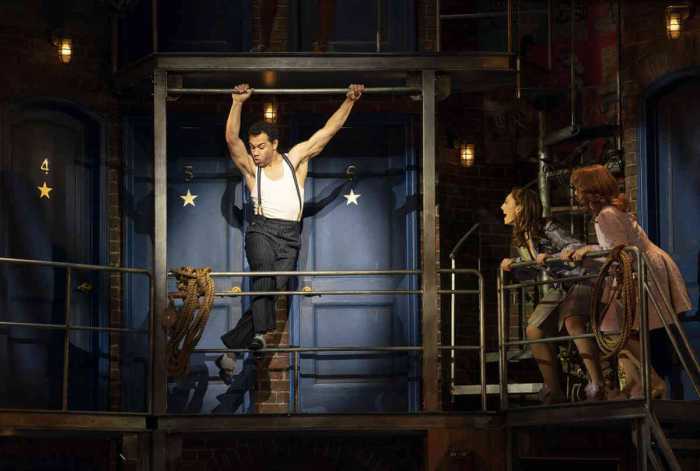

In “Dada Woof Papa Hot,” John Benjamin Hickey faces the existential angst of a queer moment

The play, directed by Scott Ellis, aims to capture urban parent angst at a crucial cultural moment when gays nationwide are now allowed to marry and become full-fledged legal parents. Sure, many of these issues — in vitro fertilization versus adoption, applying to preschools, making time for the gym, juggling sleeping schedules, age difference between parents, fidelity — are shared by straight couples. But when seen through the lens of gay dads, they promise to take on a fresh urgency.

Hickey is a supremely versatile actor equally at home on stage and screen. In 2011, he won the Best Featured Actor Tony for his portrayal of Felix in “The Normal Heart.” For the past two years, besides guest starring on “The Good Wife” and “Modern Family,” he’s played the lead in WGN’s period drama “Manhattan” about the Manhattan Project. He appears opposite Cate Blanchett in “Truth,” the political biodrama that hit movie theaters in mid-October.

What’s more, he’s conquering the airwaves, hosting a new radio show on Andy Cohen’s Sirius XM channel called “My Favorite Song,” where he dishes about beloved tunes with celebrity buddies like Sarah Jessica Parker.

Gay City News sat down with Hickey in his West Village apartment and chatted about his role in “Dada Woof Papa Hot,” gay dads, choosing sperm, and negotiating extramarital sex.

DAVID KENNERLEY: You’ve been busy doing TV and movies since your Tony-winning turn in “The Normal Heart.” What brought you back to the New York stage?

JOHN BENJAMIN HICKEY: What brought me back was this play specifically. As soon as we did the first reading a couple of years ago, I knew it was something very special. Peter Parnell is an insightful author who’s written brilliant plays — highly imaginative, theatrical pieces often steeped in history. This play felt extremely personal to me, so I responded to that.

More importantly, it opened up a new chapter for me in queer theater. It’s not a play about coming out or fighting for gay rights or the war years of the epidemic. I came of age when Tony Kushner was writing plays and we had urgent political reasons to be performing theater. It is not a play that asks straight people to understand, accept, or love us. It’s a brand new thing. Of course there are echoes of where we come from and how much we’ve sacrificed to get to this moment. But it’s the first play that doesn’t ask for tolerance from anyone. We are now assimilated.

DK: The play is astonishing. Within the first minute there’s talk of treasure trails, crotch adjusting, cocaine, a threesome with an ex-boyfriend, and bottoming — all casually discussed over dinner at a trendy Manhattan restaurant. How do you feel about such a candid portrayal of contemporary gay dads, especially at Lincoln Center?

JBH: That stuff doesn’t shock me because I’ve heard it many times before, but to a straight audience it may be pretty shocking. But what’s most shocking is how unpolitical the play is. For all the candor of that first scene and throughout the entire piece, the play is essentially about existential malaise for both gay men and for straight couples in their late 40s and early 50s. How do you stay a couple when you are now more than a couple, a family? This is a brand new question for gay guys. Now that you mention it, I guess some subscribers are going to freak out a little.

DK: What are some of the themes?

JBH: The play portrays the experience of same-sex couples. What does the child call each of you? Whose sperm do you use? Who does the child biologically belong to? How do you negotiate that triangle? My character is not the biological parent, and he feels slightly on the outside. That’s really interesting stuff to bring up. We face some of the same challenges [as straight couples] and yet we are different. A child will ask questions like, “Where is my mommy? Where did I come from? Who do I belong to?” A friend’s child put it very beautifully, “Oh I get it Daddy, your sperm just got there faster.”

DK: Tell me about your character, Alan.

JBH: I was deeply attracted to this character because he is not entirely ready. He always wanted to be monogamous, but he never thought he’d ever live in a world where he could be married and be a parent. It’s a play about growing pains and a huge shift from who we were, signaling a new paradigm, a new normal. As somebody who has done a lot of gay parts — and a gay man myself — I was incredibly excited by it.

DK: At one point, Alan says, “I just don’t feel gay anymore.” What does he mean by that?

JBH: It’s an amazing speech he has halfway through the play, describing coming out in the early ‘80s. He says he wanted faithfulness, he didn’t want to tart around. But he never imagined he’d get married and become a parent, and now he doesn’t feel gay the way he used to feel. Becoming like everybody else isn’t exactly what he wanted either. I think that’s where we are right now. How do we move forward with an identity that separates us from everybody else? It’s nice to be different. We’ve celebrated this difference for many years.

DK: Alan pines for the good old days with Rob before parenthood. He misses not having to compete with his child for his husband’s attention. He is brutally honest, wouldn’t you agree?

JBH: I am not a parent and hadn’t thought about that. You live as a couple on this beautiful island of love. Then along comes this miniature person who demands all of your attention. You co-parent, and hopefully do it equally. But in this specific situation, one wanted a child more than the other, which happens with straight couples also. And two of them share DNA. My character misses being the center of his husband’s universe. In some ways, the play is about the end of narcissism in gay culture. We love the gym, we love our bodies, we love each other’s bodies. We celebrate that. But in many ways, parenting is about forgetting about all that. You don’t have time to do that stuff any more. You have to give up the old notion of self.

DK: One character feels that gay marriage is duplicating heterosexual normative behavior. Is that such a bad thing?

JBH: One of the characters says, well, you asked for it, so you are getting all the problems that go along with it — good luck with that. It reminds me of that New Yorker cartoon with an elderly couple [watching the news on television]. One says to the other, “Gays and lesbians getting married — haven’t they suffered enough?”

DK: The script is so sharp and authentic. I’m not even a gay dad, but it feels like playwright Peter Parnell is secretly recording conversations I’ve had with gay dads. Do you feel that way?

JBH: I agree. The minute I read the script, it struck me that it sounded like me, like a lot of people I know. A couple of friends read it, and it scared them in a beautiful way. It was so perceptive about the melancholy attached to the liberation. Once you have all of your rights, now what? We are a group, a tribe, and for our entire history we’ve had to bang on the door — the closet door, the door of marriage equality, a door of a club you want to get into. Now, a lot of doors are open. What do you do now?

Also, the play is not whiny. It asks, although I have every reason in the world to be happy, what’s wrong? Any human being in the world can appreciate that existential paradox.

DK: The play depicts couples negotiating rules about extramarital sex. Do you think that’s authentic?

JBH: That’s one of the great moments of the play. The younger guy, Jason, goes through this long list of do’s and don’ts and then ends with something about licking ass. My character, Alan is gobsmacked and says, “Wow, that last one must have taken a lot of negotiating.” Jason replies, “You have no idea.”

DK: Your long-term partner, Jeffrey Richman, is a writer and an executive producer on “Modern Family,” the first hit network TV show to feature gay dads. Do you ever talk with him about the unique challenges of gay parenting?

JBH: He talks to his gay parent friends all the time, he’s that voice in the show. We’ve talked about Mitch and Cam over the years, I love those characters and those actors. Alan and Rob are different from those guys, so we haven’t compared the two. Jeff has read the play and loves it so much. He is a huge champion of me doing it.

DK: Do you ever get questions like, “So, when are you guys gonna get married and have kids?”

JBH: A lot of people ask it. I realize they have the best intentions, but it seems like something your grandmother would ask. Sometimes I feel like, “It’s none of your fucking business.” If it’s a close friend, it’s a good question. Jeff and I have talked about it, but we are in such a good place and love where we are right now, there hasn’t been a push forward as far as that goes. I’m so grateful that we can now be asked that question. It’s a wonderful problem to have.

DADA WOOF PAPA HOT | Lincoln Center Theater, Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater, 150 W. 65th St. | In previews, opens Nov. 9 and runs through Jan. 3: Tue.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat. at 2 p.m.; Sun. at 3 p.m. | $87 at telecharge.com or 212-239-6200 | One hr., 40 mins., no intermission