Cherry Jones in Sarah Treem’s “When We Were Young and Unafraid,” at New York City Center through August 10. | JOAN MARCUS

BY DAVID KENNERLEY | Cherry Jones is one of the most formidable forces on the New York stage today. This past season, the 57-year-old actor was nominated for a Tony Award for her exquisite portrayal of Amanda Wingfield in “The Glass Menagerie,” which ended its impressive run in February. Alas, she had tough competition, losing out to Audra McDonald (“Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill”).

No matter — she’s doing just fine, thank you, having snagged her share of glory, including the best actress Tony in 1995 for “The Heiress” and in 2005 for “Doubt.” Just last year, she was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame. And besides, she did win the 2014 Outer Critics Circle Award for playing Amanda.

Not that glamorous trophies are a goal for the esteemed actor.

“I’ve never cared much about awards because it’s all kind of ridiculous, but I still [wanted] us to win,” Jones said of the play itself in a recent interview with Gay City News, adding that she was thrilled to be reunited with the cast at the ceremony. “Doing the play was such an extraordinary experience for all of us and we’ve gotten very close. I’m surprised at my own feelings about it.”

Cherry Jones chats about her latest role, the Tonys, and the hullaballoo over hugging her girlfriend

Incredibly, Jones’ follow-up to “Glass Menagerie” is not on Broadway at all, but rather a relatively small play titled “When We Were Young and Unafraid,” premiering at MTC’s New York City Center Stage 1.

Directed by Pam MacKinnon (“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf”), the feminist-minded drama centers on Jones’ character Agnes, who runs a bed and breakfast on an island off the Washington State coast that doubles as a secret safe house for troubled women. One such visitor, a battered young woman who fled from her brute of a husband, has a profound influence on Agnes’ 16-year-old daughter. Also in the mix are an angry black lesbian separatist and a lonely male songwriter whose marriage recently imploded.

The year is 1972, before the Roe v. Wade decision or the enactment of the Violence Against Women Act –– a time when there was scant legal recourse for abused women.

What drew her to the role of Agnes in such a modest production after her star turn on the Great White Way? She had workshopped the drama with playwright Sarah Treem at Sundance and was intrigued by the complex characters and the portrayal of empowered women.

“I didn’t honesty think I was right for it then,” admitted Jones. “But there’s a soft spot in all actors — when someone says they want you, it’s hard to say no. I thought I should make this work for the rest of the cast and the play. I’m giving it my best shot.”

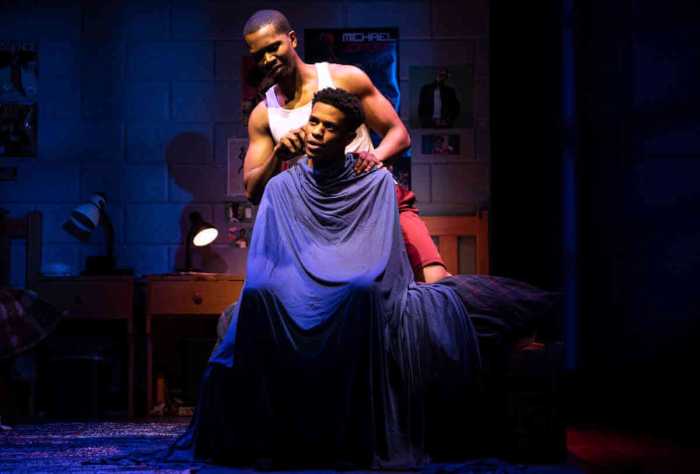

Cherry Jones with Morgan Saylor and Zoe Kazan. | JOAN MARCUS

The New York-based actor — she lives in the West Village — is stoked to be sharing the stage with a gifted supporting cast that features Cherise Boothe (“Ruined”) as the militant lesbian, Zoe Kazan (“The Seagull”) as the battered refugee, Morgan Saylor (Showtime’s “Homeland”) making her stage debut as the defiant daughter, Penny, and Patch Darragh (“Our Town”) as the songwriter.

“Zoe is doing astonishing work,” Jones enthused. “Cherise makes that whole arc succeed so beautifully. She convinces me that everything she says is completely rational. Little Morgan Saylor is also amazing. That kid is not intimidated by anything — she leads the charge.”

When I suggested that Amanda Wingfield and Agnes are both doting mother figures who are loners, Jones agreed, but noted sharp contrasts between the two characters as well.

“Amanda has the incredible flamboyance of that Southern lady,” said Jones. “I knew those women growing up in the South. Agnes is a little awkward as a human being and in many ways has almost winterized herself. She loves Penny but she’s not a natural mother. She never planned to have children and her mothering is a work in progress. When a little girl becomes a teenager, all bets are off, even if you’re the most accomplished mother. That’s what’s going on in our play.”

In many ways, Jones felt it was tricky to transition from Amanda to Agnes, especially when the language was so different. Because Treem is writing for a woman closed down, it’s more naturalistic and not the lyrical poetry of Tennessee Williams.

“I was used to all of those floral bouquets,” Jones explained of Amanda’s dialogue. “I had to figure out places to breathe because once she gets going she never stops, going off into back alleys and down mountainsides. Agnes has very short sentences, just four or five words and a period. The rhythm of it was so different, and frankly quite daunting for me.”

Jones admitted it was exhilarating to originate a role rather than reinterpret a classic, having done so several times.

“It’s fun because nothing is written in stone,” she explained, adding that they made several tweaks in previews.

Jones recalled approaching MacKinnon and Treem about one pesky passage where she couldn’t understand the motivation behind her line.

“Sarah was able to craft it so it made all the sense to me,” Jones said. “To have a living playwright with a new creation, so open to collaboration, is wonderful.”

When asked to elaborate on the play’s themes like physical abuse, sexism, and sexuality, Jones refused outright.

“I’m not an intellectual,” she declared. “I never think of themes, ever. I just focus on what my character is doing and thinking and feeling and trying to accomplish,” adding that themes are the purview of the director and playwright.

In some ways, the role of Agnes is as complex as any Jones has ever played. Agnes has spent her whole life caring for others, yet finds it hard to allow others to take care of her. Plus, she’s mystified about her sexuality.

“She has tremendous faith in her own skills,” said Jones. “Her sexuality is something that was dormant inside of her. I don’t think she had dates with men or women. Being a lesbian those days, especially in the South where she’s from, was truly out of the question. She is shut down that way.”

Although set in the early 1970s when Women’s Lib was in full force, the play still resonates for today’s audiences on many levels.

“There’s the whole abortion twist in the play,” said Jones, citing a line that refers to Roe v. Wade going back to the court. “Hanna says, ‘The times are a-changing,” and Agnes replies flatly, ‘They’ll change back.’ There’s an audible murmur from the audience when we say that every night. Now here we are almost half a century later and the last abortion clinic in Mississippi is closing.”

Despite her stellar theater track record, Jones is no stranger to film and television, winning an Emmy for her role on “24.” Yet she is more comfortable onstage than in a television studio.

“I am a stage actor, I dabble in television and film,” she said. “I don’t feel accomplished in either of those, I haven’t done it enough. I don’t have a lot of confidence and I’m not as fearless as I’d like to be. They put up with me on the set of ‘24’ and guided me a lot.”

According to Jones, on screen an actor must inherently look and sound like the character, unless highly skilled at metamorphosis like Meryl Streep.

“On stage, you can play a 60-year-old nun from the Bronx in 1964 even if you are a 50-year-old Tennessean. You can get away with transforming yourself much more.”

When Jones won her first Tony nearly two decades ago, she thanked her girlfriend at the time. It was one of the first overt public mentions of a same-sex partner by an actor — this was before Ellen DeGeneres famously declared, “Yep, I’m gay.”

“Everybody made such a fuss over my speech,” recalled Jones. “I gave her a hug when I got up to get the award. She was among a long list of thank-yous, but I didn’t say ‘my lover’ or ‘my cherished one.’ I was surprised and thrilled about the big deal because it was a good thing. After all [adopting a jocularly haughty accent], the theater is absolutely rife with homosexuals!”

“For those of us who are older, we are thrilled at the lightning speed with which it’s happened,” Jones continued, referring to advances in LGBT visibility and equality. “I remember years ago when I first heard the term ‘gay marriage’ on the floor of the Senate, uttered by Bob Dole. Even though he was speaking derisively and banning it, I thought, woo! — the times, they are definitely a-changing.”

WHEN WE WERE YOUNG AND UNAFRAID | Manhattan Theatre Club | New York City Center — Stage 1, 131 W. 55th St. | Through Aug. 10: Tue.-Wed. at 7 p.m.; Thu.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $89 at manhattantheatreclub.com or 212-581-1212 | Two hrs., 20 min., with intermission