There is a kind of violent lyricism in Philip Ridley’s “Mercury Fur,” now getting a first-rate New Group production that is — and should be — profoundly unsettling. In a dystopian New York City on the verge of destruction, a group of survivors and drug dealers break into a vacant apartment to host parties, where stimulated by potent drugs in the form of butterflies, the privileged rich can experience their most dangerous and taboo fantasies as the world crumbles around them.

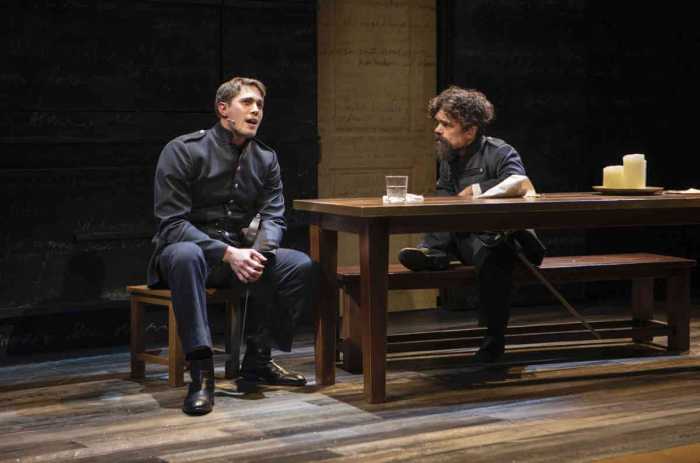

As the play opens, brothers Elliot and Darren are struggling to get a bombed out apartment ready for such a party. Controlled by the organizer Spinx, Darren and Elliot are constantly in fear for their lives, and their survival depends on adherence to a code that is implied but never fully delineated. It doesn’t need to be; their desperation tells us everything. In this case, they’ve been forced to move up the date of the party, and the pressure is on.

When Naz, a squatter in an adjacent apartment, barges in, things begin to go wrong. The boys are having particular problems subduing the Party Piece, a young man on whom the Party Guest will act out his fantasies. As Spinx arrives with a zonked out woman called the Duchess, Lola, a transgender woman whose job is to get the Party Piece ready, has her work cut out for her.

Two new plays touch the heart with very different types of lyricism

Throughout all of the chaos, we learn bits and pieces of backstory, piecing together what life was like before the first wave of destruction and seeing what the survival imperative can drive one to do. The escalating problems lead to brutality, and memories and reminders of who these characters once were pierce the haze only momentarily before desperation once again overtakes them, sending the play hurtling to its harrowing conclusion.

Under Scott Elliott’s precise and powerful direction, this play is not for the faint of heart or the squeamish. Yet for all the grand guiginol, it is a remarkably human play as well as a meditation on being able to consider the impact of one’s own actions. At the same time, the play provides no definitive answer.

The cast is uniformly excellent –– and to a person fearless. The actors’ commitment to the bold theatricality of this piece is exhilarating. Zane Pais stands out as Elliot, who bears the brunt of the conflict while trying to save his younger brother and himself. As Darren, Jack DiFalco is both trusting and powerful. The relationship dynamic between the two men recalls George and Lennie in “Of Mice and Men.” Sea McHale is appropriately threatening yet also vulnerable as Spinx. Tony Revolori, in a heartbreaking performance, is Naz, the outsider drawn into this world –– and to his own destruction. Paul Iacono as Lola is likewise affecting as her boundaries crumble. Peter Mark Kendall as Party Guest, Bradley Fong as the Party Piece, and Emily Cass McDonnell as the Duchess round out the cast, all giving fine performances.

As the play draws to a close and it appears that the sound and fury may, indeed, have signified nothing, one realizes that “Mercury Fur” has taken place in real time –– the short span in which violence, terror, and death can actually happen. Is it an existential comment or a warning? I don’t know. I do know it’s thrilling theater.

“A Delicate Ship,” the Playwright’s Realm production that just closed, is a deceptively simple play that resonates powerfully in the heart. In a story where three characters recall a Christmas Eve that changed their lives, Sarah and Sam are celebrating quietly at her apartment –– in love, they think, and possibly going to marry. Nate, a childhood friend of Sarah’s, barges in and over the course of the evening declares his love for her, explaining she is what holds his life together. The situation quickly spins out of control until Nate is finally thrown out of the apartment.

We know what the characters are thinking because playwright Anna Ziegler has them step out of character on occasion and address the audience –– their much older selves who are commenting on the action taking place. This may sound confusing, but it’s not in the least. The device gives the play its resonance because it underscores the way in which we accumulate memories, losses, questioning of the past, and experience as we move through life. As Sarah says the first time she steps out of character, “What if we just hadn’t opened the door?,” Ziegler knows that question cannot really be answered, and suggests, at least for Sarah and Sam, that making peace with not knowing is essential to surviving. Nate finds no such peace.

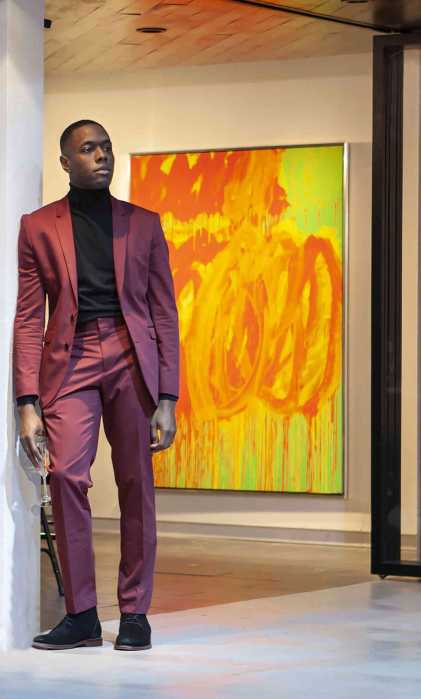

Margot Bordelon directed a cast that it’s virtually impossible to imagine could have been finer –– with Matt Dellapina as Sam, Miriam Silverman as Sarah, and Nick Westrate as Nate. Each imbued their character with believable life and offered moments that took your breath away. Dellapina’s quiet subtlety was no less realized than Westrate’s more boisterous and antic performance. Silverman, who was superb in “You Got Older” last season, offered an understated complexity to Sarah. The three worked together flawlessly.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about this play is that Ziegler is at times unabashedly poetic. We know this is literary, but it works. The abstraction and theatricality touch the heart in ways that only art can.

MERCURY FUR | The New Group at Pershing Square Signature Center, 480 W. 42nd St. | Through Sep. 27: Tue.-Fri. at 7:30 p.m.; Sat. at 8 p.m.; Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $27-$97; ticketcentral.com or 212-279-4200 | Two hrs., without intermission