I’m not that into “Star Wars,” but I’ll watch any YouTube clip of Carrie Fisher doing a promo interview with her French bulldog Gary and spouting some inappropriately true thing with the hint of a smile spreading across her hard, broad, beautiful face. She’s an aging woman who has no fucks left to give. A quirkier, even more deadpan Lauren Bacall, if you remember her.

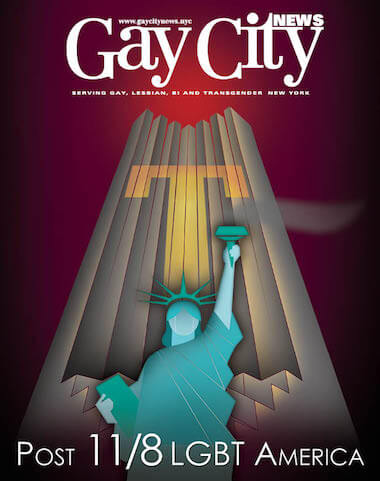

I wish she was a dyke. We’re starting to see a few, but they’re mostly young. In that age category, we’ve got Lily Tomlin, and, um, well, Lily Tomlin, who recently played what she is in the acclaimed movie, “Grandma,” an older lesbian apparently based on Downtown dyke poet Eileen Myles, who suddenly finds herself there in the mainstream at age 65.

Myles has also inspired a character on the Amazon series “Transparent,” which is kind of weird, as if this extraordinary writer can only get her props if she serves as her own doppelgänger. She and her double both participated in a firestorm via “Transparent,” in an episode featuring a women’s music festival based on the Michfest, which ended this year largely because it was attacked as transphobic.

A Dyke Abroad

Some lesbians hated the “Idlewild” episode outright as a pure display of “contempt for dyke culture.” Others declared that it got some things right, but there were elements of caricature and a completely unnecessary Nazi reference. There weren’t many lesbians (that I saw) who embraced it entirely.

I haven’t seen it, or even been to Michfest, so I can’t judge. But after spending the last couple of years watching dykes respond to everything from TV’s “The L Word” to the new Todd Haynes movie “Carol,” which I haven’t seen either, I’ve started to think more deeply about what it’s like for us dykes to begin to see ourselves represented. Both by outsiders, but also by others in our community.

Like a lot of us, I’ve spent a lifetime working for, or at least longing for, lesbian visibility. Not just in the streets or in politics, but on big and small screens, in books and paintings, anywhere that might allow us to claim a little space in our own cultures.

Now that we’re finally starting to appear, I’m anxious, squeamish even. Either because the representations have nothing at all to do with me, or because they come pretty close but get important things wrong, or maybe because they get too many things right and I want to protect my peeps from prying eyes and tidy things up for general consumption.

One of the problems is that there’s almost no context to understand lesbian culture, or style, or even bodies. For most of American history, lesbians have barely appeared even as stereotypes. When we finally turned up it was in pulp novels and movies as (white) serial-killing bombshells with equally porny bombshell girlfriends, or as librarians too miserably dowdy to get men, or women either.

Our invisibility is a legacy not just of homophobia and misogyny, but actual laws that made our existence illegal. Until relatively recently, no one was allowed to write knowingly –– or approvingly –– about queers. Born into heterosexual families, we grew up without an oral tradition, only later discovering who we were or what legacies we had to draw on.

Even grown up, we dykes could barely see ourselves, because we faced the additional obstacle of being female. Until recently, unescorted women had little access to public spaces. Even now, we run risks that men don’t. Gay men at least could find each other in cruising spots, public toilets, and eventually bathhouses.

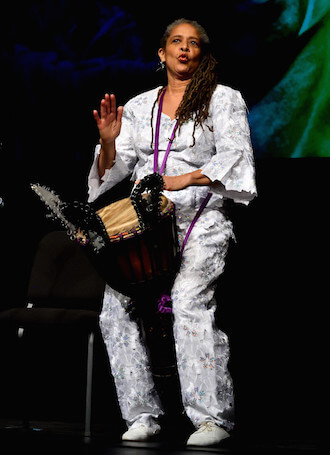

When I gradually came out in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, I still only had fragments of a history. Poems by Audre Lorde or Adrienne Rich. A few lines from Sappho. Experimental texts by Gertrude Stein, and a postcard photo of her with Alice that I carried around for years and taped up next to my mattress. Gradually I learned about things like potlucks and women’s music festivals. Women’s colleges. Sports clubs. Bars!

And of course I found lesbian activists who had carved out niches in the many social justice movements that excluded them until they started busting out for themselves in street activism, but also whole utopian movements reconsidering economy, language, culture, absolutely everything that shapes a society. But these were dismissed as hilarious failures because “lesbian” was attached to the word “separatist.”

For a while, I wanted to reclaim all this in a kind of natural history museum that might feature rotting Birkenstocks and flannel, because even stereotypes seemed better than nothing at all. But now, what I’d really like to see is a huge film project that takes on the history of lesbians, in the widest interpretation of that word, with the sweeping ambition of “Roots.” It’s not like we lack resources. The Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn is right there waiting for you.

Kelly Cogswell is the author of “Eating Fire: My Life as a Lesbian Avenger,” from the University of Minnesota Press.