But on several occasions, the newspaper reported on his extracurricular visits to his home town, New York.

In April 2005, Scalia gave a 30-minute address to students at New York University, and he got a stark –– perhaps embarrassing –– reminder that the personal is indeed political.

Eric Berndt was a 24-year-old NYU law student. As Duncan Osborne reported, Berndt had little use for Scalia as a legal profession role model, describing him as a “homophobic bigot” whose language is “demeaning” to the queer community. Two years before, the conservative justice, in his dissent in the Lawrence v. Texas sodomy case, had written, “The Texas statute undeniably seeks to further the belief of its citizens that certain forms of sexual behavior are ‘immoral and unacceptable,’ the same interest furthered by criminal laws against fornication, bigamy, adultery, adult incest, bestiality, and obscenity. [The 1996] Bowers [ruling] held that this was a legitimate state interest.”

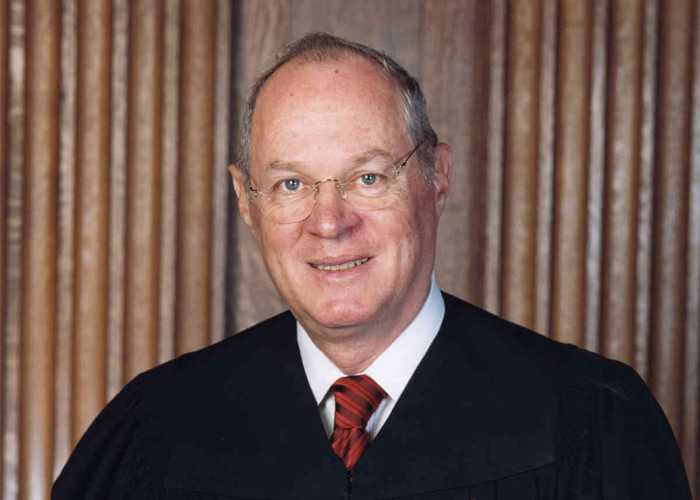

Berndt was willing to challenge Scalia on his legal reasoning, asking him if he believed that the “liberty interest” identified in Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion in the sodomy case might outweigh the “state interest” he identified.

Then Berndt drove the point home, asking Scalia, “For example, do you sodomize your wife?”

According to the law student, there was a “huge collective gasp” among the 400 in the audience, though Berndt said he heard that in an overflow crowd of 300 watching a live feed in another room, a cheer went up. Scalia’s jaw dropped, Berndt recalled, and he looked toward his Secret Service protection.

Berndt worried little that Scalia never answered the question.

“He should not be morally shielded from that,” he said. “He is asserting that it is not a serious invasion of liberty… My question was a symbolic act, a gay man against a homophobe.”

Berndt’s symbolic defiance did not go unanswered by NYU officials, however. In a school-wide email, Richard Revesz, the law school dean, wrote, “One student posed an extraordinarily rude, immature, and inappropriate question. Such a show of incivility to any individual invited to be a guest of the Law School, let alone to a Supreme Court justice, has no place in our intellectual community.”

Berndt was not shy about responding, writing in his own mass email, “It should be clear that I intended to be offensive, obnoxious, and inflammatory. How am I to docilely engage a man who sarcastically rants about the ‘beauty of homosexual relationships’ (at the Q&A) and believes that gay school teachers will try to convert children to a homosexual lifestyle (at oral argument for Lawrence)?”

Later the same year, Scalia was back in Manhattan, this time as grand marshal of the Columbus Day Parade. There, he faced a protest from several dozen LGBT activists, who were joined by a longtime community ally, Chelsea Assemblymember Dick Gottfried.

Gerard Cabrera, who was then president of the Out People of Color Political Action Club, told Gay City News’ Andy Humm, “I think generally Supreme Court justices are not viewed as public figures the way politicians are. But the fact that Scalia has so politicized his own office by going to extremes when writing about his animosity toward the LGBT community, he sets himself apart from the rest of the court — except for [Clarence] Thomas — who are supposed to be just interpreters of the law.”

Other politicians chose not to join Gottfried in picketing Scalia but rather to participate with him in the parade. Mayor Michael Bloomberg marched, though when his spokesperson, Ed Skyler, was asked whether the mayor was “happy, sad, or indifferent” about the justice’s role as grand marshal, the response was, “Indifferent.”

Senator Chuck Schumer also marched, explaining that it was appropriate that “the first Italian-American associate justice” on the high court serve as grand marshal. Schumer hastened to add, “But I’m fighting to keep people like him off the court.”

Scalia himself was not particularly chatty with the press that day. Asked how being grand marshal differed from his marching with Xavier High School as a Queens youth, all he would say was, “I’m older.” He became downright exasperated when asked where he saw gay issues going on the high court, saying, “I have no idea.”