San Francisco Opera (SFO) celebrated its 100th anniversary with its annual June Festival, which dovetails with Frameline’s fabulous LGBTQ+ Film Festival (held in the Castro, Mission and Oakland). The company provided a very compelling showing.

June 16 witnessed the rare gala concert at which nobody canceled and none of the assembled stars sang less than well. A wide range of music sounded, from Monteverdi to John Adams. Karita Mattila proved spellbinding (and seemingly vocally rejuvenated) in Kostelnicka’s narration. Patricia Racette cleaned up with a really impressive edition of “Losing my mind.” Ailyn Pérez did a fabulous job with “Vicino a te” opposite Michael Fabiano, exciting but unremittingly *forte*. Lawrence Brownlee dazzled with the Count’s final rondo from “Barbiere.” The evening’s most beautiful singing was its quietest: Lucas Meachem’s gorgeously limned Pierrots Tanzlied. Former Music Director Donald Runnicles took top conducting honors.

Current Music Director Eun Sun Kim — given a hero’s welcome by the audience — did a very creditable job leading “Madama Butterfly,” bringing out poignant instrumental details.

Karah Son played a highly touching, powerfully expressive Butterfly; it was not a very individual timbre, but her voice did everything she and Puccini asked of it: an admirable performer.

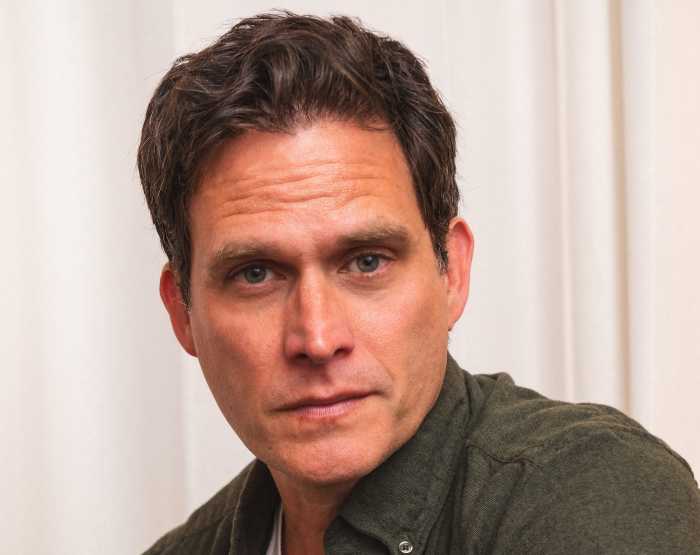

Fabiano — a natural for the handsome, cocky sailor and his resonant music — offered more dynamic nuance than usual: up there with Aragall and Alagna. Hyona Kim made a very strong Suzuki and Meachem a slightly light-voiced but excellently phrased and inflected Sharpless. These days, any reputable company needs to approach Puccini’s opera — based on a play by San Francisco native David Belasco — with thoughtful exploration of the Orientalizing libretto. Oddly, Japanese director Amon Miyamoto seemed intent on making Pinkerton (after all, a trafficker in underage sex) more sympathetic and making *his* emotional journry more central — not, to my mind, the problems “Butterfly” now poses. To do this, Miyamoto introduced a “30 years later in America” silent prologue in which the now adult biracial Trouble — son of Butterfly and Pinkerton — gets a manuscript about his history from his ailing father. Improbably, Suzuki — still in her native garb after three decades in America — is a family retainer, obviating some but not all of the narratological problems the approach of the action we see reflecting Trouble’s reading of the memoir poses (no one witnesses Butterfly saying “Con onor muore”, for example). Moreover, the actor’s frantic miming takes center stage all too often, including a Lifetime-style redemptive hug with Pinkerton Senior at the opera’s close, quite eclipsing Butterfly’s suicide. Interesting touches along the way; but a distracting, wrongheaded concept.

“Die Frau ohne Schatten” — given its 1959 US première by SFO — returned as a triumph for Runnicles and the orchestra (observing traditional cuts) and David Hockney’s gorgeous design. Roy Rallo’s blocking proved rather perfunctory, and the Apparition of the Young Man aroused laughter, but at least Rallo didn’t litter the stage with extras. Strauss’ score really favors the three leading women and all three experienced sopranos did well. Camilla Nylund, always a class act, sang a pristine, increasingly commanding Kaiserin. If somewhat uneven, Nina Stemme was moving, and sometimes thrillingly “on” as the Dyer’s Wife. Veteran Linda Watson found an excellent role in the Amme, with remarkably supple vocalism and a great look for the role. Johan Reuter — reduced in volume since a decade ago at the Met — was a noble if undergunned Barak. David Butt Philip coped very solidly with the Kaiser’s ungrateful music and Stefan Egerstrom’s sturdy Messenger impressed. Cellist Thalia Moore and concertmaster Kay Stern aced Strauss’ wonderful solo opportunities. The audience roared approval.

The new co-production “El ultimo sueño de Frida y Diego,” launched in San Diego by Gabriela Lena Frank and Nilo Cruz, joins “Omar” as the season’s best new opera. Frank’s music is at once compelling and highly sophisticated, the choral writing particularly acute. It pleased a wonderfully diverse crowd (confoundingly, this marks SFO’s first-ever Spanish-language opera). Unlike some “biopic” works, Cruz’s libretto takes a highly imaginative view of iconic Mexican artists Kahlo and Rivera centered on 1957’s Day of the Dead. He yearns for her to return to life to help him die. She relents and risks a renewal of bodily and emotional pain for the chance to paint again, spurred on by smooth, affecting countertenor Jake Ingbar’s Leonardo, a gay actor wanting to return to Earth as Greta Garbo. (A repeated arpeggiated allusion to “Peter Grimes” underlines the queer context, left undefined in relation to Kahlo’s sexuality.)

Presiding over the life/death interface, part of Mexico’s pre-Christian legacy, is the skeletal Catrina — a fantastic vocal and dramatic performance by soprano Yaritza Véliz. Veteran baritone Alfredo Daza made a convincing Rivera: Both his vocal estate and Frank’s music, for him, shone more strongly in Act Two. Holding Lorena Maza’s impressive staging together was dynamic, chameleonic mezzo Daniela Mack, in another bravura portrayal both vocally and interpretively. The season’s outstanding Adler Fellows (Young Artists) — imposing mezzo Gabrielle Beteag and clarion tenor Moisés Salazar — both took supporting parts. Roberto Kalb did a fantastic job in the pit; one hopes he leads it in New York and that Frank and Cruz aren’t asked to “supersize” the opera, which dazzles just as it exists now.