The opening and closing shots of “Passing” hint at a more daring film than the one Rebecca Hall, an actor making her directorial debut, actually made. The first scene gradually brings a world into focus. The images are blurry, the sound muddled. The camera’s POV is a foot above the sidewalk, looking at people’s legs as they walk by. Gradually, the soundtrack gets louder and clearer. The scene turns out to be about a woman gazing at another woman. Irene (Tessa Thompson) runs into her old friend Clare (Ruth Negga), and she looks up from her feet to her face. At the end, the reverse occurs. The camera pulls back to a point where snow blows across the screen so heavily that it almost blots out the scene.

Irene and Clare, both light-skinned biracial women, knew each other as children but fell out of touch in their teens. Clare now passes as white, living with a racist husband (Alexander Skarsgard). When he meets Irene, he takes her for white as well, and uses the N word in front of her. (Both women laugh, although the underlying anxiety is palpable.) Neither woman has to worry about money, but Irene, whose husband (André Holland) is a doctor, participates in early civil rights activism without recognizing her own colorist attitudes towards their servant. Irene and Clare spend more and more time together, especially in Harlem nightclubs.

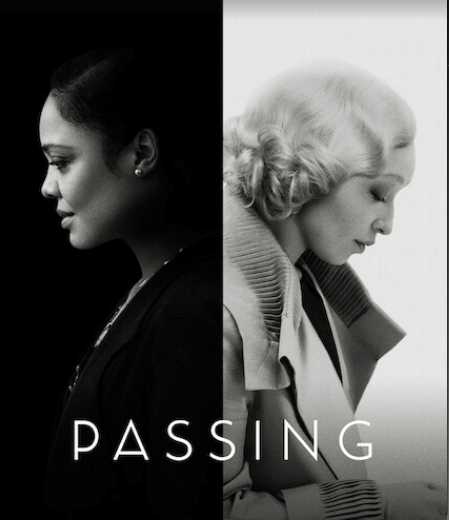

“Passing” may be a little too good at capturing the ambience of repression. Even at its most dramatic, the tone is fairly quiet. Hall lets the cinematography speak for her characters. The fact that the film is in black and white, and framed in 1.33, alludes to its setting. It also expresses the story’s ambiguity in visual terms. Between the extremes of those two colors, a thousand variations in between are displayed. Its symbolic use of color may be on-the-nose at times, as when snow represents the power of whiteness in the final scenes, but at least Hall lets her images speak as much as her dialogue.

Based on a 1929 novella by Nella Larsen, who was a biracial woman, “Passing” was made by a director who has been perceived as white, indeed a rather posh British woman. She had to investigate her heritage for herself as an adult to learn that her maternal grandfather was Black. She says, “If I look at my mother now I can see clearly that she is of African ancestry, but that wasn’t clear to me as a child.” She now sees the political dimension and psychological pain behind the passing which occurred in her family.

Racial passing isn’t the only kind of closeting that “Passing” explores. Irene and Clare seem to have a degree of desire for each other. When they greet each other in a restaurant, Clare stares at Irene till they speak. It plays as a form of cruising — they may have a history, but the way the scene is filmed suggests a strong erotic charge. Their quick return to friendship, albeit mediated by the presence of Irene’s husband or other men, hints at the same, as do scenes like the one where Irene tells her husband she’s worried about her son picking up “queer ideas” about sex from other boys. Casting Thompson, whose partner is Janelle Monae and who rejects labels but says she’s attracted to men and women, enhances this subtext.

Tessa Thompson is made up and dressed to look glamorous according to white beauty standards, with straight blonde hair and a pearl necklace. “Passing” hints at the projects of two films by Black lesbians, Cheryl Dunye’s “The Watermelon Woman” and Dee Rees’ “Mudbound.” All three attempt to make up for the erasure of Black people in classic Hollywood movies. “The Watermelon Woman” lays this out explicitly, showing a video store clerk researching a Black actress who played servants in the 1930s and 1940s and discovering a life as a lesbian that contradicted her submissive onscreen appearance. “Mudbound,” also made for Netflix, plays like a Black counterpart to William Wyler’s version of 1940s America in “The Best Years of Our Lives.” Its style might be classical, but it speaks from a perspective, drawing on Rees’ grandparents’ lives, that was shut out of Hollywood at that time.

Hall’s direction of actors brings out a mannered rhythm of speech that recalls 1930s films. She says, “Part of the concept of this film was to turn it into the great, female driven 1930s noir it should have been if Hollywood studios had made noirs with Black female leads in the ‘30s. That was the genesis. The fantasy of discovering this lost film that might have existed in a better world.”

At its worst, “Passing” mistakes opacity for subtlety. For a film based on an acclaimed book, its script is its weakest aspect. The characters are thinly drawn. In its first half, “Passing” lays out the outlines of Irene and Clare’s lives, especially Irene’s barely acknowledged dissatisfaction, but the rest doesn’t do much to flesh them out. It’s too reliant on pregnant pauses and glances. “Passing” touches on an array of themes without delving too deeply into any, although at least it trusts the spectator to make their own way through deeply charged territory.

PASSING | Directed by Rebecca Hall | Netflix | Opens at the IFC Center Oct. 27th