Foundation preserves work of one of America’s greatest sculptors in serene Queens setting

The Garden Museum of Isamu Noguchi is an aesthetic oasis designed around an indoor/outdoor space where the work of one of America’s most important sculptors is shown in the simple, elegant manner in which the artist saw fit.

Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), born in California to an American mother and a Japanese father, was raised in Japan until the age of 13 when his family moved to Indiana. He studied pre-law and sculpture in New York before deciding to become a sculptor. In 1926, Noguchi saw an exhibition of Constantin Brancusi in New York that had a profound effect on him. With a Guggenheim Fellowship, Noguchi went to Paris in 1927 and worked in Brancusi’s studio over the next two years. The modern elements of Brancusi’s work—reductive forms, the specific object, a spiritual quality and the integration of the base into the sculpture—were themes Noguchi would explore in his sculpture for the rest of his life.

Noguchi, an internationalist, did not belong to any particular movement. He also designed a broad range of products for everyday living, including tables, chairs and sofas, along with his famous Akari lights. These, along with stage sets and interior and landscape design, were all seen as an extension of his sculpture. All the work shares an elegant, organic quality and benefits from the Japanese aesthetic tradition that does not draw distinctions between practical objects and works of art.

In the 1960, Noguchi began work with stone carver Masatoshi Izumi, on the island of Shikoku, Japan, in a collaboration that was to last the rest of his life.

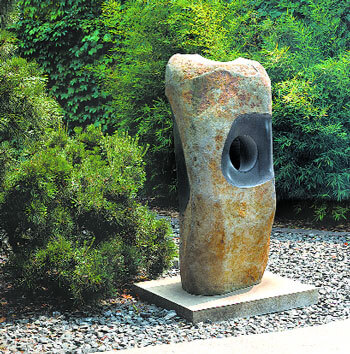

In the garden court, two dozen or so large-scale sculptures are placed. The paradoxes in the work are apparent, such as East versus West, rough versus smooth, organic versus geometric. His signature monoliths are here along with some more unusual pieces. One granite sculpture, “The Big Bang,” 1973, is a low-lying stone seemingly broken into five pieces that appears to have almost occurred naturally, cut and smoothed just enough to make it art. There are two “tsukubai (water holders), from 1962, in pink granite that collect rain water, and even a large basalt sculpture, “The Well” (1982), whose surfaces are covered in falling water and acts as a well. “The Illusion of the Fifth Stone” (1970) is unusual in that all of the shapes are smoothed and rounded without the usual angular additions.

While wandering the paths of the garden or sitting on a bench under a tree, you could be anywhere; you are first and foremost in the world of Isamu Noguchi.

Aside from the permanent exhibition, a special exhibit entitled “Isamu Noguchi: Sculptural Design,” conceived and installed by Robert Wilson, the theatrical designer and visual artist, comes off as somewhat forced and disorienting. With its odd lighting, incongruous sound track and surreal use of props, the exhibit seems to be much more about Wilson and his concerns than a showcase for Noguchi’s design achievements.

The Garden Museum can be experienced as a sanctuary, a serene place to contemplate art. To quote Noguchi: “Call it sculpture when it moves you so.”