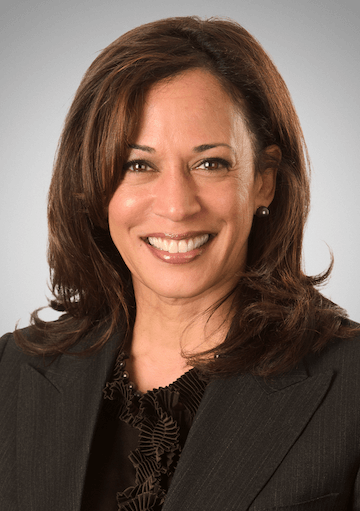

The Office of California Attorney General Kamala Harris again successfully defended the state law ban on so-called “conversion therapy” on LGBT minors. | EMILYSLIST.ORG

BY ARTHUR S. LEONARD | A California law that prohibits state-licensed mental health providers from engaging in “sexual orientation change efforts” — so-called “conversion therapy” — with minors has withstood another First Amendment challenge.

A unanimous August 23 decision by a three-judge panel of the San Francisco-based Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a ruling by US District Judge William B. Shubb that the law, SB 1172, does not violate the religious freedom rights of mental health providers who wish to provide such “therapy” to minors or of the potential patients themselves.

In a previous ruling, the court rejected the plaintiffs’ claim that the law violated their free speech rights. Those challenging the law argued that such therapy mainly involves talking, making the law an impermissible abridgement of freedom of speech. The court countered that the law was a regulation of health care practice, which is within the traditional powers of the state. The court found that the state had a rational basis for imposing this regulation, in light of evidence in the legislative record of the harms such therapy does to minors.

Ninth Circuit again upholds California’s law protecting LGBT minors

In this new case, the plaintiffs were arguing that their First Amendment religious freedom claim required the court to apply strict scrutiny to the law, putting the burden on the state to show that the law was narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling state interest. The plaintiffs contended that the law “excessively entangles the State with religion,” but the court, in an opinion by Circuit Judge Susan P. Graber, said that this argument “rests on a misconception of the scope of SB 1172,” rejecting the plaintiffs’ claims that the law would prohibit “certain prayers during religious services.”

Graber made clear that the law “regulates conduct only within the confines of the counselor-client relationship” and doesn’t apply to clergy — even if they also happen to hold a state mental health practitioner license — when they are carrying out clerical functions.

“SB 1172 regulates only (1) therapeutic treatment, not expressive speech, by (2) licensed mental health professionals acting within the confines of the counselor-client relationship,” Graber wrote, a conclusion that “flows primarily from the text of the law.”

Her conclusion was bolstered by legislative history, ironically submitted by the plaintiffs, which showed the narrow application intended by the legislature.

“Plaintiffs are in no practical danger of enforcement outside the confines of the counselor-client relationship,” Graber wrote.

Plaintiffs also advanced an Establishment Clause argument, contending that the measure has a principal or primary purpose of “inhibiting religion.”

Graber countered with the legislature’s stated purpose to “protect the physical and psychological well-being of minors, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth, and to protect its minors against exposure to serious harm caused by” this “therapy.”

The court found that the “operative provisions” of the statute are “fully consistent with that secular purpose.”

A law that has a secular purpose with a possible incidental effect on religious practice is not subject to strict scrutiny under Supreme Court precedents Again, the court pointed out, religious leaders acting in their capacity as clergy are not affected by this law.

The court also rejected the plaintiffs’ contention that a minor’s religiously motivated intent in seeking such therapy would be thwarted by the law, thus impeding their free exercise of religion. The court pointed out that “minors who seek to change their sexual orientation — for religious or secular reasons — are free to do so on their own and with the help of friends, family, and religious leaders. If they prefer to obtain such assistance from a state-licensed mental health provider acting within the confines of a counselor-client relationship, they can do so when they turn 18.”

The appeals panel acknowledged that a law “aimed only at persons with religious motivations” could raise constitutional concerns, but that was not this law. Its legislative history, the court found, “falls far short of demonstrating that the primary intended effect of SB 1172 was to inhibit religion,” since the legislative hearing record was replete with evidence from professional associations about the harmful effects of SOCE therapy, regardless of the motivation of minors in seeking it out.

Referring in particular to an American Psychiatric Association Task Force Report, Graber wrote, “Although the report concluded that those who seek SOCE ‘tend’ to have strong religious views, the report is replete with references to non-religious motivations, such as social stigma and the desire to live in accordance with ‘personal’ values.”

Graber continued, “An informed and reasonable observer would conclude that the ‘primary effect’ of SB 1172 is not the inhibition (or endorsement) of religion.”

The panel also rejected the plaintiffs’ argument that SB 1172 failed the requirement that government be “neutral” concerning religion and religious controversies, and it rejected the assertion that prohibiting this treatment violates the privacy or liberty interests of the practitioners or their potential patients. Quoting from a prior Ninth Circuit ruling, Graber wrote, “We have held that ‘substantive due process rights do not extend to the choice of type of treatment or of a particular health care provider.’”

Attorneys from the Pacific Justice Institute, a conservative legal organization, represent the plaintiffs. The statute was defended by California Attorney General Kamala D. Harris’ office. Attorneys from the National Center for Lesbian Rights, with pro bono assistance from attorneys at Munger, Tolles & Olson LLP, filed an amicus brief defending the statute on behalf of Equality California, a statewide LGBT rights group.