This month brings to a close a year of almost compulsory self-reflection for the LGBTQ community as a whole. The 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots spurred discussions and displays far and wide striving to link the past to the present.

Two important exhibitions of photography mounted in New York in the last 12 months did some of this work of remembering, of looking back to push ahead.

“The Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop,” an eponymous retrospective, is currently on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, until February 9, and “Christopher Street,” works by the artist Sunil Gupta, ran from April 30 to June 1 at the Hales Gallery in West Chelsea (a hardbound catalog, currently showing as out of stock at stanleybarker.co.uk, is available from Amazon).

Both shows were shot mostly in black and white, and capture street life in or near Greenwich Village in the 1970s and early ‘80s. Archival as much as artistic gems, the two series are in conversation with one another about that potent era of sexual freedom and visibility that Stonewall inaugurated, a period when gay men, and some determined trans folks, claimed public space for themselves in this metropolis.

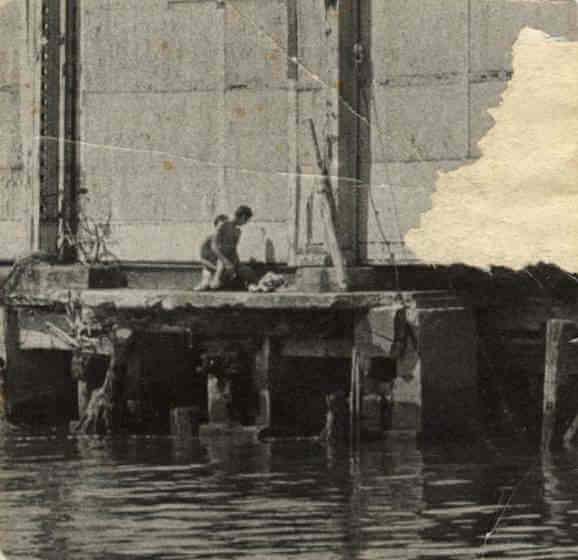

The Baltrop show features 120 photographs taken between 1969 and 1986. The earliest of these were shot while the photographer was enlisted in the US Navy and capture his fellow servicemen at ease, as well as some battleship functions. In subject and composition, these works prefigure the much larger corpus that Baltrop produced following his discharge in 1972 when he found his way to a location in downtown Manhattan cut off from the straight world by structural and economic neglect. In the heady post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS decade, a network of abandoned, decaying piers with massive sheds atop them stretched along the Hudson River below 14th Street. They became a destination for gay guys to hang out and have sex. Baltrop trained his lens on this crumbling haven and its transient denizens in leisure and lust.

Baltrop’s signature technique was the wide-angle shot. His photographs frequently capture figures — whether solo, or in couples or clusters — dwarfed by an expansive backdrop of dereliction. For example, there is the photo of two naked white men, one backing the camera midstride, the other hands akimbo looking sideways towards the lens surrounded by a tangle of collapsed iron girders and wooden beams. In various states of undress, Baltrop’s subjects stroll, stand, sunbathe, fellate, recline, crouch, watch, and wait.

In the absence of virality, in both human-immunodeficiency and social-media senses, men made different choices then about exposing themselves. The resulting photographs portray what the writer Adrian Nicole LeBlanc called a random family, a collective cobbled together from different sources and cemented, in this case, by bodily fluids.

There is no clearer document in the show of Baltrop’s inclusion in this family than the close-up portrait he made of Marsha P. Johnson, the trans activist and organizer who is said to have thrown the first bottle in the Stonewall riots. In Miss Marsha’s eyes we see comfort — she evidently feels safe posing for this photographer — but also a question mark. “Who really are you?” she appears to be thinking.

The essays in the exhibition’s 300-page catalog describe an intersection of class, isolation, and race that helps explain why Baltrop, who died in 2004, remained unrecognized as an artist during his lifetime. “Baltrop is black, apparently from the slums of a large northern city which I infer to be New York,” wrote the military doctor of then 24-year-old Baltrop, the year of his Navy discharge.

This retrospective is part of a posthumous validation of Baltrop’s work by the art establishment. Pieces of his art have also been acquired by the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The photographs of Sunil Gupta show us what Baltrop’s lens does not. Gupta draws in close to his subjects to render them as street portraits. The artist turned his attention to the respectable streets of the West Village, particularly Christopher, the principal gay commercial artery of the era.

Yet, Gupta’s shots clearly articulate how respectability itself was being redefined. In one shot, a svelte young man, secure in his fey posture and gait, walks down a traffic filled street clad in tiny gym shorts and a sagging hoody unzipped to reveal his bare chest. Every man’s “package” is prominently accentuated, in the style of the day, to act as a live advertisement for sex.

Whereas Baltrop gives the wide-angle view of man in his environment, Gupta provides the close-up man on the street. Where Baltrop shows the naked gay male animal in a wild industrial habitat, Gupta shows what those same animals looked like in clothes fashioned to make their identities visible to the public. The wirebound exhibition catalog forfeits analytical essays, ubiquitous in these books, for as many images of the series as can possibly fit, each printed in a full-page layout. But the story neither begins nor ends in the photographic images themselves. Gupta’s trajectory as their creator speaks to New York City’s history as a destination for people with artistic aspirations, a dynamic now severely encumbered by astronomical rents in the same buildings that are backdrop to the men he photographed in their short-shorts and crotch-bulging bellbottoms.

“Christopher Street was shot in New York in 1976 when I spent a year studying photography at the New School,” Gupta writes in a brief, bold-fonted statement on the catalog’s back cover. “I spent my weekends cruising with my camera. In retrospect, those pictures have become both nostalgic and iconic for a very important moment in my personal history and the struggle for gay liberation that had far reaching consequences across the globe.”

In Gupta we also have a valuable example of the queer veteran artist of color whose talent and production are given their due in and by the establishment while the artist himself is still active. He is based in London, has work in the collections of numerous art institutions such as the Tate Museum and MoMA, and has been the subject of exhibits worldwide.

In Baltrop’s oeuvre, the past meets the present in one portrait from the artist’s Navy period. Pictured are three young African American enlisted men in uniform. The youngest one, around 19, who is also closest to Baltrop’s camera, points his tongue vertically out of the corner of his mouth in a display often seen in selfies of people his age today.

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF ALVIN BALTROP | Bronx Museum of the Arts, 1040 Grand Concourse at E. 165th St. | Through Feb. 9: Wed.-Thu., Sat.-Sun., 11 a.m.-6 p.m.; Fri., 11 a.m.-8 p.m. | Admission is free | bronxmuseum.org | Exhibition catalog published by Skira at skira.net/