On a warm October evening, several dozen runners tumbled into The Holler, a bar bedecked with Halloween decor. The group had participated in Great Day’s Oct. 21 running tour, Queer Ghosts of Brooklyn, making their way past checkpoints rich with stories from the borough’s LGBTQ history.

Inspired by Hugh Ryan’s non-fiction book, “When Brooklyn Was Queer,” co-creators Anthony Torres and Tony Ruiz led the group past Walt Whitman’s residence, the Naval Cemetery Landscape, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Sands Street, Walt Whitman Park, and a sign honoring Black journalist and co-founder of the NAACP Ida B. Wells, befiore ending at Fort Greene park. Brooklyn remains on the unceded territories of the Lenapehoking, a matriarchal society on Turtle Island that “thrived on the absence of restrictive genders.”

Torres said he felt drawn to combine his love for Ryan’s work with his passion for running.

“What really stuck with me from reading that book was all this incredibly important and incredibly close-to-home queer history that was deliberately erased,” he said.

Many attendees, including Luke Sherman, were surprised and inspired by how visible and vibrant Brooklyn’s LGBTQ community was in the early 20th century.

“I did not know that there was such a large cluster of gay establishments,” he said. “It inspired me to imagine alternatives to the societal structures that led to the empowerment of the fascist government today.”

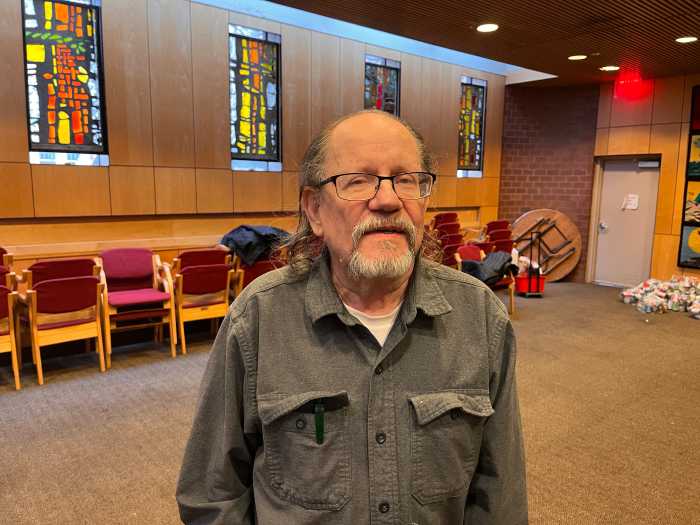

Ryan, praising the event, said he did not expect his book to have such an impact on the community that it would help foster running tours.

“Every author dreams that their book will have a life beyond the day it comes out,” he said. “It’s incredible to see that people not only care about this history, but want to incorporate into their lived life.”

As the book offers a plethora of Brooklyn’s streamlined LGBT history, Ruiz, the co-organizer, understood the need to narrow down the run for practical purposes but hinted at more possible runs throughout the borough. “If you get to read the book, you will realize Coney Island is a whole other thing and would need a whole other run to be done.”

Elle Durst, a recent transplant from Atlanta, appreciated the education component and noted the importance of keeping LGBTQ history amidst gentrification.

“There’s such deep history,” they said. “I don’t want to be part of the problem of it being erased.”

Such gentrification and erasure of queer and trans people of color, immigrants, and disabled people seemed to make inclusion a challenge on the run. In preparing the book, Ryan elaborated on white supremacy in archiving in the first place.

“All things in the archives have a relationship to power,” he said. “I had to work against that actively at all times, or I would have presented a skewed history because queer people of color, queer immigrants, have always been here.”

The run included fundraisers and a petition for the city to memorialize these historic areas of Brooklyn. Alongside the book, folks looking to learn more about Brooklyn’s LGBT history might also consider: the Unassimilated Blood And Water walking tour, which covers Brooklyn’s first ever Filipino neighborhood and includes evidence of queer life; dozens of listings on the NYC LGBT Historic Sites for Black History Month; or the Brooklyn Community Pride Center.