I saw the Met’s lavish 1982 Franco Zeffirelli production of “La Bohème” for the 18th time on December 3. If not an epochal event, it was a very good repertory performance.

Of prime importance: New York-born James Gaffigan, in his first Met conducting gig, proved a real asset, with a well-textured, alert reading throughout. I expect we’ll hear more of him locally. The cast was uniformly strong without any one member being so outstanding as to “grab” the evening — as happened, for example, in a 2004 outing in which the star-power of Anna Netrebko and Peter Mattei, as Musetta and Marcello, wiped everyone else off the stage.

The Bohemians all looked age-appropriate (in this work that matters). I first saw Ailyn Pérez as Mimi in her conservatory days at the Academy of Vocal Arts in 2005. Even then, she was an appealing, vulnerable figure with a warm, appropriate sound. She has gained immeasurably in pitch accuracy and is now an international artist, with some very fine achievements, including last season’s Met Thais. Yet security on top forte notes remains inconsistent, and she’s developed dodges (diminuendi, rehearsal pianissimi) around less-than-comfortable moments. Though she had a lot to offer as Mimi, I had the sense that maybe she’s been an over-attentive pupil of Renata Scotto’s legacy: sometimes the constant artfulness in phrasing and dynamics gets in the way of straightforward vocal character projection. Plus, she had to cope with a flood of cell phone beeps — some emergency alert pertaining to Rochester! — during the crucial “Sono andate?”

Perez did display real chemistry in convincing interplay with her AVA colleague Michael Fabiano, whose Rodolfo I first encountered 10 years ago with the Philadelphia Orchestra. He’s well-voiced for the part. Fabiano — an admirably out gay leading tenor with strong opinions — can sometimes power-sing his way through entire evenings, but on this occasion he explored the text’s poetry and also the music’s many dynamic shadings. As in “Mefistofele” a few weeks ago, he struggled against stridency at virtually every high climax. If he can resolve that issue, Fabiano would be hard to beat as Rodolfo. As an interpreter, he’s leagues ahead of the over-the-top self-lovefest offered hereabouts by Vittorio Grigolo.

Lucas Meachem made a spirited Marcello, notable for excellent high notes. Angel Blue — a terrific Mimi last year — brought her uncommonly beautiful voice to Musetta, but the out-of-control “diva” blocking and gestures imposed on her in Act Two were perhaps too enthusiastically enacted. Christian Van Horn sounded somewhat baritonal for Colline’s lower reaches but offered a sound, likable performance.

I’m always suspicious of the Met’s British casting directors casting British artists in roles easily filled by North Americans. Surely the audibly veteran Donald Maxwell is hardly irreplaceable as Benoit/ Alcindoro. But Duncan Rock, the affable Schaunard, proved to be about more than his evident gym preparation: the voice has a distinctive individual timbre and carries well even in ensembles. One thing revival director J. Knighten Smit should do forthwith is damp down the egregious prancing onto the stage of Gregory Warren, a Parpignol not exactly channeling the vocal strength of Met predecessors James McCracken or Robert Nagy in the role.

But the evening was a success. My guest — an insightful woman well acquainted with Broadway — had never seen an opera. (“Bohème,” and this crowd-pleasing production, are good bets for a first try at a Met opera for virtually anybody.) She liked the piece, loved the sets, and was very impressed to learn that the singers worked unamplified. Her only objection was to the endless intermissions, now endemic at the Met — and surely one of the main obstacles preventing Peter Gelb from attaining the valid theatrical values he often discusses. With Puccini, the intermissions are now regularly longer than the acts. Why?

“Il Trittico,” Puccini’s trilogy of one-acts, had its world premiere at the Old Met one hundred years ago. Originally this year’s revival was conceived as a vehicle for both the 50th anniversary of Plácido Domingo and — as a triple bill — for Kristine Opolais, a beautiful, camera-ready actress in alarming vocal decline. I couldn’t countenance the idea of hearing Opolais ruin “Suor Angelica,” the middle opera, to which she had been limited. So I waited for December 12, the cover show, in which understudies were slotted for three principal roles.

Jack O’Brien’s detailed staging remains confident and bold, though I still don’t like the swaying nuns upstaging Angelica during “Senza mamma,” when surely no one else should be onstage. Still, O’Brien had more success with this tough show than any of Peter Gelb’s other Broadway Babies — some baffingly afforded repeated attempts — have earned.

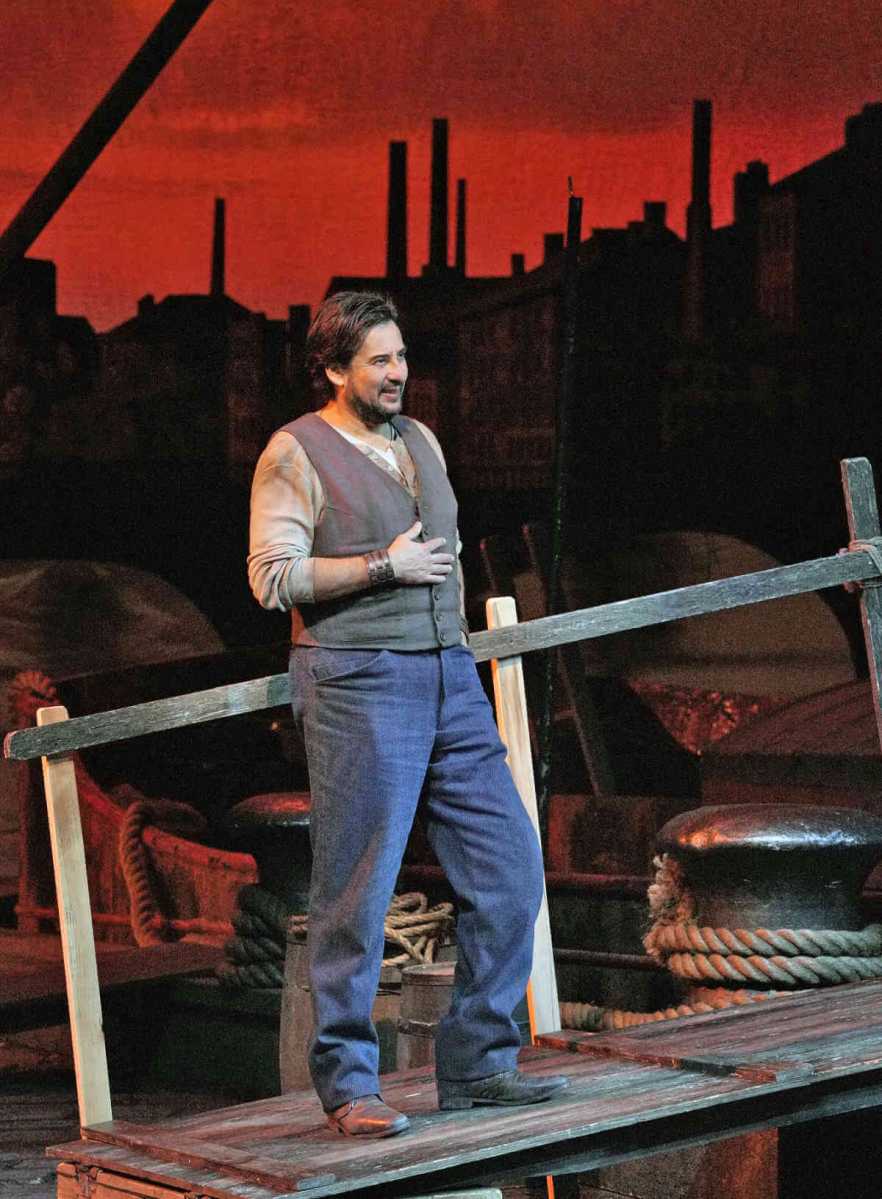

In the enjoyable if not really combustible “Tabarro,” large-voiced Tatiana Melnychenko made an acceptable Giorgetta, and through restraint and idiomatic utterance the non-dulcet Lucio Gallo far exceeded expectations as Michele. Marcelo Álvarez looked and sounded rejuvenated as Luigi, Puccini’s toughest tenor “sing.” The first soprano ever to make a Met debut as Angelica, the appealing Elena Stikhina sounded just glorious, meeting all Puccini’s vocal demands with silky yet carrying lyricism. This was also a role debut, so greater verbal specificity will come. (If Stikhina wants to last longer then such “five years and out” Russian predecessors as Nina Rautio and Marina Poplavskaya, she should radically rethink her insane repertory list, which includes Senta, Salome, and the “Forza” Leonora.) Stephanie Blythe repeated her chilling, fabulously voiced Zia Principessa.

As Gianni Schicchi, Domingo — announced as ill — offered large presence and still-potent sound, if not the last word in specificity. The season that Florence Easton created Lauretta, she also sang Santuzza, Lodoletta, and Fiora. So the Met needn’t cast it with itty-bitty voices; Kristina Mkhitaryan looked pretty and sang decently but on a very small scale — she might have made an apter Suor Genovieffa than Maureen McKay, a committed performer but lacking the requisite vocal purity. Atalla Ayan (Rinuccio) did highly creditable work, and Blythe returned as a hilarious Zita.

All the participants in “Tabarro” registered positively. Maurizio Muraro was idiomatic luxury casting as Talpa — and later as Simone in “Schicchi.” “Angelica” needed two sisters ejected from the convent: a comprimaria mezzo whose voice was worn 20 years ago but somehow keeps getting cast, and a wealthy soprano who had no right to display her amateurish deportment and patchy voice on a Met stage. Kevin Burdette shamelessly hammed while cawing through what he obviously conceived as the title role of Puccini’s “Spinelloccio.”

Bertrand de Billy conducted with high competence but less specific finesse than he has brought to some other Met assignments.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.