Daniel Richter lends a wicked wit to absurdist European rituals

This is Daniel Richter’s first show in New York. In Germany and elsewhere in Europe, he is a big deal and much—very much—has been written and said about his provocative work.

It seems Richter was an abstract painter for a short while and has recently taken to making politically charged figurative paintings of urban confusion and violence. These are very large-format paintings done in an apocalyptic, illustrational style. Well-versed in the conventions of 19th century history painting, from France to Russia, Richter uses this format to capture enigmatic moments in seemingly staged or ritualalized events.

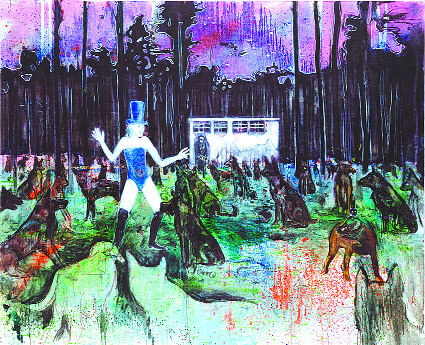

In “Tuwenig,” a Cabaret-style performer—boots, top hat, bare legs—entertains, if that is the right word, a pack of glaring wolf-dogs in a sylvan setting at night. In “Tefzen,” a showgirlish, befeathered circus performer poses appliance model-style in the midst of what appears to have been a gladiator battle among animals, the victors still snarling and the vanquished rigid in defeat and death.

This is a theater of absurdist spectacle, cruel, sometimes solemn, and delivered with “what you see is what you get” bluntness. A panoply of painterly technique and reference is employed to convey all this, from the deliberately awkward to the skillfully rendered. The variety of paint applications is dazzling. Color ranges from psychedelic to fecal. The combination of elements in the paintings sometimes verges on being hokey.

Just what the political stance is never clear and Richter’s anarchistic response to query is fairly opaque. He’s determined to be socially engaged as well as a painter. This is fine, at least until the illustrators at Rolling Stone catch up to his madness. The sources of these works range from famous news photos and sundry magazine clippings to children’s books. There is a feeling of familiarity about all the paintings even though the goings on are outrageous and sometimes deeply funny.

There is a sense of inevitability in the proceedings, as if it has been enacted before and will likely be again. This theatricality may be saying more about the cyclical nature of history than it wants to and for now the paintings pass as art and wicked entertainment.