Karel Funk draws on traditions of hyper-realism to create psychological buzz

Group shows abound in New York’s summer art scene.

Digging into this extremely focused, solo debut exhibition of paintings by Karel Funk at 303 Gallery in Chelsea provides a nice change of pace.

Funk paints people. He paints them realistically, so much so that he has been linked to the 1970s hyper-real self-portraiture of Chuck Close. Funk’s too are heads, up close, in nearly excruciating detail.

Paintings following in this lineage can lean in a variety of directions—focusing on the camera’s process, as was the case with Close’s early work; toward the attributes of paint itself, as in the recent work of Jenny Dubnau; or in the direction of another kind of human hyper-reality, as in the paintings of Gregory Gillespie.

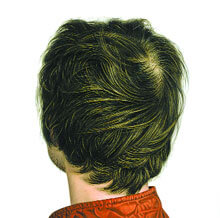

In each case, the resonance between the subject and the art-making creates a psychological buzz that sustains the viewer beyond simple recognition. Funk’s work hovers at the nexus of the three possible alignments. The small size of each panel and crisp-clean ground behind each head reinforce the photographic frame’s seeming absence. Masterful paint-handling signals a sure and patient hand applying layers of acrylic glaze, and Funk’s acute and loving observation of skin and hair summons sensory memory—whether of a bristling crew cut, or of slightly chapped lips.

Hair takes on a special role in these 11 paintings. All of them portray men who are mostly turned from the viewer, have eyes closed, or obscured by a hat or hood. Looking in order to know Funk’s subjects becomes a game of sensory inventory. Funk’s fidelity in defining the differences among them draws us in, and our observation becomes a game of sensory inventory. He depicts a wreath of buzzed stubble in “Untitled (headphones)” that marches down from the edge of a bald spot toward the collar of a T-shirt. The follicles grow fewer, dancing erratically along the way. Neck hair never looked so fabulous.

In other paintings, the sun-streaked, curly, tussled and shorn reveal a more traditional romance with the heads of youthful men. And whiskers, especially those that are sparse suggesting an adolescent subject, all offer conventional allure.

There is something perfect about the constancy of tone and tight variety of treatments among these paintings. Even the attire of the subjects seems tastefully coordinated. Perhaps it’s the weather in Funk’s Manitoba home that dictates all the Gore-Tex, in hats and in hoods. Or maybe these guys shop together. In any case, it’s this last detail of cultural information that reveals the youthful management of the subject matter. It will be interesting to see if Funk has the chops to entertain the kind of imperfection that makes work mature.