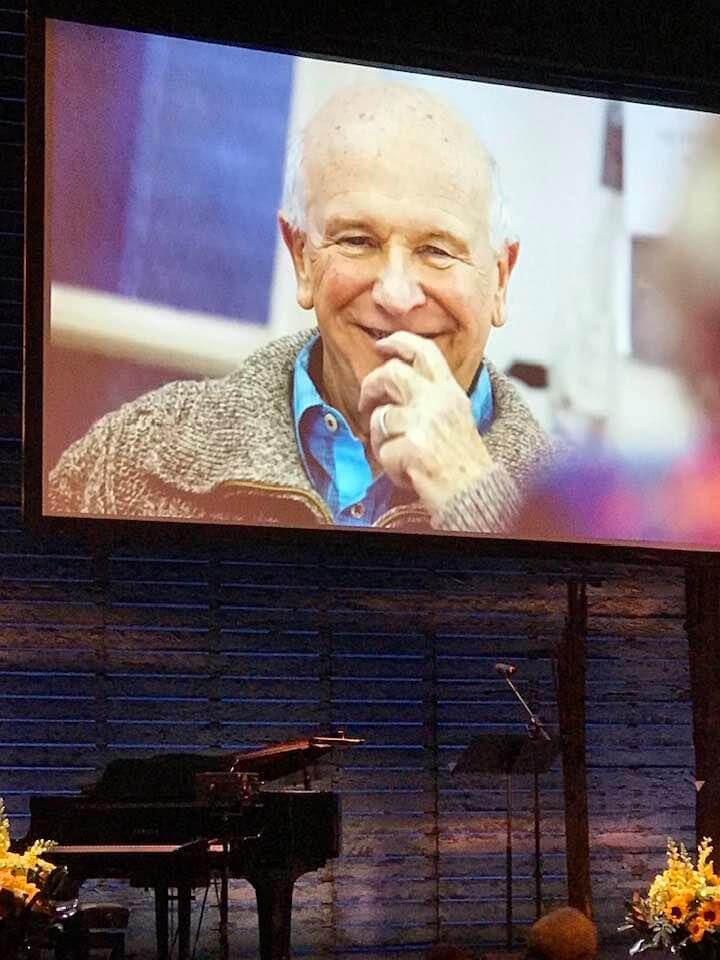

Eighteen months after he died of COVID, the life of playwright Terrence McNally was celebrated in a packed house on November 1 at the Schoenfeld Theatre. Tributes poured in from the theater artists he so loved and nurtured, while McNally’s own words were highlighted from his plays, speeches, and personal communications with friends.

For almost three hours, the theater community laughed, reflected, reminisced, cried, and contemplated the hole in our hearts in the absence of this brilliant, passionate voice and human being whose work spanned more than six decades.

Jonathan Groff set the tone for the service with a scene from McNally’s “And Things That Go Bump in the Night” that McNally brought to Broadway in 1965 (with a gay leading character!) when he was 25. “I know it’s fashionable being morose,” the character says, “but I love being alive!”

Audra McDonald had trouble composing herself as she reflected on someone who was the lodestar of her career and a friend — “He did both of my weddings,” she said — for 26 years. From “Master Class” to “Ragtime” to a revival of “Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune,” McDonald read comforting emails from McNally that helped her overcome some rough patches.

She quoted McNally, revealing, “The main thing I feared in the ‘Corpus Christi’ controversy was losing my nerve.” That play centered on a “gay Jesus” character who brought bomb threats to McNally’s theatrical home at the Manhattan Theatre Club and sent death threats to him. A scene was performed with Joshua, played by Tony winner Andrew Burnap of (“The Inheritance”), marrying two of his apostles (Telly Leung and Dominic Cuskern.) “Respect the divinity in your partner,” Joshua tells the men — and McNally surely did that in partners from actor Robert Drivas (who later died of AIDS) to Gary Bonasorte (who died of AIDS in 2000) to the love of his life, Tom Kirdahy, who put together this splendid gathering.

Friend Edgar Bronfman, Jr. said he had the honor of investing in two of McNally’s “flops, which we now call ‘worthy’ shows” — the first production of “It’s Only a Play” in ’78 and the musical of “The Visit” in 2015. He also quoted McNally’s wisdom: “Dance begins with courage, not steps.”

McNally’s little brother, Peter, talked about sharing a bedroom with him for four years as kids in Corpus Christi.

“He had posters of Maria Calls, James Dean, and Shakespeare on the wall,” he said, “and I was allowed to have a small picture of Mickey Mantle.” He spoke of the magical visits to New York for his brother’s opening nights and recalled when McNally and Kirdahy renewed their vows, which was presided over by Mayor de Blasio at City Hall in 2015.

Lin Manuel Miranda and John Kander, two of Broadway’s greatest composers, read from McNally’s speech to the League of American Theatres and Producers in 1991 when he talked about being taken to Broadway from Texas by his parents as a child to see Ethel Merman in “Annie Get Your Gun” — something that Nathan Lane would later quip was “the primary cause of homosexuality in the 1950s.”

Longtime friend Don Roos, a screenwriter, gave the single funniest speech I’ve ever heard at a memorial service or even a comedy club. When they first met in the late ‘70s and McNally said he was a playwright, “I thought he was going to ask me for money,” Roos remembered. He said, “I was 27 and he was 43 — really old. But he was the youngest man I knew.”

Roos recalled McNally’s mother, Dot, saying “she could take all of us.” He said McNally worried about how his mom would react to a speech in one of his plays about sodomy and the joys of being entered. “She told him it was his best work ever,” he said.

Lane and John Benjamin Hickey performed a scene from “Lisbon Traviata” about gay opera queens, while soprano Angel Blue sang “Ah! Non Credea Mirati” from Bellini’s “La Sonnambula.”

Christine Baranski, yet another “McNally actor,” read from his 1998 commencement speech at Julliard urging the graduates to “make art that matters and make yourself heard” and telling them that “art is the oldest way we have to try to tell the truth about the world” — words that informed the entirety of McNally’s career.

Several speakers, including Jonathan Lamma, talked about how encouraging McNally was with their young children when they expressed interest in writing.

Lynne Meadow talked about how she came to produce McNally’s “Bad Habits” in 1973 at her fledgling Manhattan Theatre Club and how their rich collaboration endured for decades.

Murray Abraham, an Oscar winner, (“Amadeus”) said, “He was my champion!” and that getting cast in “Frankie and Johnny” and working with McNally was “the luckiest day of my life.”

Playwright Matthew Lopez, who received a Tony for “The Inheritance,” said McNally was “a shape shifter. There is no typical McNally play.” He added, “I told Hal Prince I wanted to be a playwright and he gave me Terrence’s phone number.” That led to an internship during McNally’s “A Man of No Importance” (2002) as well as mentorship, which showed him “it was possible to be gay and live a life of love and dignity.”

Director and actor Joe Mantello, also overcome with emotion, spoke of the big chance McNally took on him by having him direct “Love! Valour! Compassion!” off-Broadway in 1994 about gay men in a country house under the shadow of AIDS and transferring to Broadway. He wore a scarf McNally gave him 25 years ago that he wore to all his subsequent openings. He said McNally wanted him to take curtain calls with him on opening nights — which Montello was averse to. He said McNally didn’t do it out of ego, but because “it showed you believe in taking pride in your work.”

John Glover reprised his Tony winning dual role as twin gay brothers in “Love! Valour! Compassion!” (1995) — one “bad,” one “good.” Michael Urie read from “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” for which McNally wrote the book — and the Spider Woman herself, Chita Rivera, walked out to proclaim that she was “Terrence’s favorite dancer!” And then she talked about how he “helped mold and shape me” and got her to “make them hear you!”

Nathan Lane, perhaps the quintessential McNally actor, had to stop frequently during his tribute to cry, but talked about how McNally would deliver “a personal note every opening night (pause) with a $1 bill inside — like something your aunt would give you on your birthday.”

He said, “We had a 30-year collaboration — though sometimes it made me feel like a ‘made man’ in La Cosa Nostra.” Lane said McNally “was a hero to the LGBTQ community,” and indeed while McNally did not like the label “gay playwright,” gay themes were prominent from his off-off-Broadway days to the end.

“He was our Chekhov,” Lane said, “only funnier.”

Tyne Daly performed a scene from her turn as diva Maria Callas in “Master Class” when she talks to a group of Julliard students: “The work we do matters. If you sing honestly then I will feel repaid,” Daly said.

Video of McNally’s acceptance of the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2019 Tonys had him saying, “Not a moment too soon.” He was on portable oxygen at the time.

McNally’s husband, Kirdahy, was a lawyer helping people with AIDS when they met and fell in love in the Hamptons in 2001. Within months, McNally told him that he had lung cancer and that he did not have to stick around, but Kirdahy did for 20 more years.

“We held hands whenever we could,” said Kirdahy, who spoke of how McNally helped him realize his potential and become one of Broadway’s preeminent producers (Tonys for “Hadestown” and “The Inheritance”). He recounted the harrowing story of getting his weakened husband out of New York by car when COVID hit in March 2020 because McNally wanted to be on the ocean in their Florida condo. McNally did end up hospitalized with COVID, given his many underlying conditions, but Kirdahy lobbied hard to be by his bedside in heavy protective gear so they could hold hands at the last moment.

“You words made the world a safer, more beautiful place,” Kirdahy said. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house, but all felt embraced by the love McNally left behind.

On Wednesday, November 3 at 3 p.m. a plaque was dedicated at McNally’s former Village home at 29 East. Ninth Street by the private Historic Landmarks Preservation Center. Kirdahy, Tyne Daly, and Brian Stokes Mitchell were on hand.

Also on November 3, the lights on Broadway were slated to be dimmed at 6:30 pm in honor of McNally on what would have been his 83rd birthday.