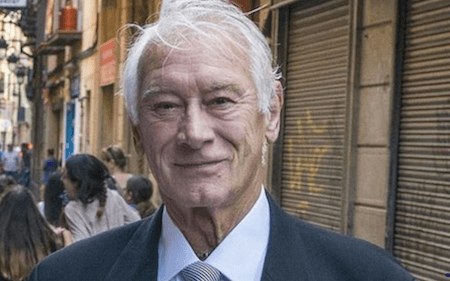

A beautiful new print of Orson Welles’ seldom seen “Chimes at Midnight” — his stitching together of Shakespeare’s various Henry IV plays, which just might be the greatest filmed Bard ever — in a recent revival at the essential Film Forum was an unquestioned cultural highlight of the new year. Key to that film’s awe-inspiring success was the performance of the then-31-year-old Keith Baxter, whose charismatic portrait of Prince Hal put him on the map. The handsome, sparklingly witty, and candid actor — today, the very definition of “silver fox” — was recently in town to introduce the film at Film Forum and sat down and chatted with me.

“We never realized during its filming that we were making a masterpiece,” Baxter said. “We knew that it was a great script [chuckles] with wonderful actors and it was such fun to make. Those who never knew Orson have this image of an overwhelming presence, but he was fun. So was Sir John Gielgud, whom Orson deferred to as if he were a young actor, not that Sir John ever demanded that. All of us in the theater admired Gielgud more than Olivier, really, because he had this innate modesty and this incredible voice. I was never directed by Orson. No one was.

“If you have Gielgud and the speech, ‘How many thousand of my poorest subjects are at this hour asleep!’ Well, here’s the window and there’s the light, and John said, ‘Well, should I start?’ Orson said, ‘Well, yes.’ And Gielgud stepped in and spoke the speech. I mean he knew the speech because he’d done it in recital, and at the end, the crew applauded. They hadn’t necessarily understood the English, but I think they’d never heard an actor speak for two minutes without stopping. And Orson came in and said, ‘That was wonderful, John.’ John said, ‘Do you really think so?’ And Orson said, ‘We have to do it again because if there’s a technical error, you will probably be on Broadway then, and we won’t have you.’ Sir John said, ‘Oh, yes! I can do it again,’ and he did.

Keith Baxter recounts extraordinary life with extraordinary people

“People find the film so glorious now, and ultimately so heartbreaking. For those in the industry or whatever, the knowledge of what happened to Welles gives it a subtext that is very sad. But we didn’t think that when we were doing it, naturally. We were just having the most terrific fun.”

Baxter had been out of acting work for a while and washing dishes In a London restaurant when he auditioned for the stage version of the film just before Christmas in 1959.

“I was 26 and another boy, a waiter, told me that Orson Welles was in town auditioning for a Shakespeare play he had cobbled together from the ‘Henry IV.’ I got a telephone number and they said, ‘Yes, you can audition for Mr. Welles tomorrow morning at 10.’

“I went and there were all these actors in a huge line. I finally got on around 2 p.m. Welles was a huge star then, after ‘The Third Man,’ and he was all in black, like I am today. He told me, ‘It’s very late and I’m very sorry for keeping you waiting.’ That was the first instance of his incredible politeness to actors, whether they were Sir John or someone playing a small part. He loved actors and might get angry with the crew, but with actors he always went out of his way to be very tender and fun. You can’t imagine the laughter, everybody loved him. Margaret Rutherford, a great actress, said, ‘Working with him is like walking where there’s always sunshine,’ and Jeanne Moreau adored him.”

Baxter witnessed the filming of the battle scenes, which many consider unmatched in all cinema: “We had shut down for lack of money. He had only about 150 horsemen and maybe only two or three days to shoot them. I went down with his wife, Paola, to see what the charge would look like. And they repeated it. Of course, Orson was a master of cutting, so quick, and he would reverse the negative, so he made 150 look like thousands, with a lot of intercut scenes with a small group. It was all shot in the Central Park of Madrid, the Casa de Campo. You know, there’s not one gruesome shot in the film, maybe one spearing but it’s cut away from, and there are no heads rolling.

“We had dinner later in Alicante, after the false start of his film of ‘Treasure Island,’ and he talked about what he wanted the film to be for its audience, who might think because it’s Shakespeare, it’s about his time, something that happened hundreds of years ago. But it’s not, anymore than ‘Hamlet,’ which had just been a big hit on Broadway [with Richard Burton]. He wanted the audience to realize that the world of ‘Chimes at Midnight’ was an England that had utterly changed since World War II.

“In ‘Chimes,’ there are castles and forests, which would disappear with gunpowder. And so the great duel between Hotspur and Hal signals the end of that. Hotspur always wears silver, like Sir Galahad, to represent the end of chivalry, while the king and others always wear black. To Orson, it was an important detail, to represent the end of romance and chivalry with the death of Hotspur. I find the music here extraordinary, these wordless voices singing, like mourning, a keening that gets more and more intense during the battle.”

I observed that “Bonnie and Clyde,” two years later, got all the credit for its “groundbreaking” visceral use of violence through swift editing, but Welles had actually gotten there first, and much more subtly. Baxter agreed.

“His genius always did lie in the cutting room,” he said. “He was so fast, and he had this wonderful eye because as a boy he had been a painter. There’s the robbery scene at the beginning, where we all dress up in that forest, that’s like a cathedral, with the leaves falling. The pace of it and the music is wonderful — “didididi” — as we’re running through the wood, and then he cuts to Sir John saying, ‘Can no man tell me of my unthrifty son? I would to God, my lords, he might be found.’ It was thrilling, cutting to that.

“Orson used to say, ‘That big fireplace in the tavern, no wonder the boy wanted to go to the tavern and sit by the fire and have fun.’ We filmed the scene in the castle — no windows — and so cold you could see our breath. He created this whole thing, and Sir John’s performance is really iconic.”

“Chimes” was young Baxter’s second film with Gielgud, as they had appeared in “The Barretts of Wimpole Street”: “But you can hardly see me because I was one of the many brothers and it was filmed in Cinemascope [with its inordinately wide screen], so we were just set dressing. You only see me when I step in to say good night to Jennifer Jones [playing Elizabeth Barrett Browning].

“She was a film star and didn’t mix with any of us. I don’t mean that she was nasty, but she was a film star and acted like one. Like most British actors, Sir John never did, Judi Dench doesn’t either, now. It’s a period that is gone forever, and of course it’s a simply terrible film. The 1934 original version was much better, and John used to say, ‘Oh, I’m not as good Charles [Laughton]!’ He was a man of utter modesty.”

Baxter met Welles only once after “Chimes.”

“It was New Year’s 1972. Paola had a house in London, his daughter Beatrice was there. I saw a lot of Paola, who was adorable, the best influence on his life. But then she went back to America, as did Orson.

“The American Film Institute wanted to fly me out to LA and put me up at the Chateau Marmont for their big tribute to him. He said, ‘Please come if you can,’ but I couldn’t. He thought going back to California would bring him money for filming, but the disastrous New York Times notice for ‘Chimes’ saw to it that that never happened. It was the crowner of his Act Three — he was sort of finished, there were no offers for him. And I think it broke his heart.

“Around 1976, I was on my way from Hawaii where I had played a crooked evangelist on ‘Hawaii 5-0.’ I stayed for four days with my friend Brenda Vaccaro, and she said, ‘Why don’t you go see Orson? He eats every day at Ma Maison.’ I think they treated him.

“I said, ‘I haven’t seen him for such a long time and he’s got a new woman and I’m still friendly with Paola… We adored each other, but our lives have moved on.’ Finally, Brenda lent me her car and I drove to the restaurant and, in the parking lot, as the valet was about to park it, I saw Orson coming out.

“He was elephantine. He’d been big, but he still had to wear padding as Falstaff. Unbelievable, with a waiter on each side of him helping him down the steps to his taxi. I just stood back near this big bougainvillea, and I realized later that there were tears in my eyes. I didn’t jump out and say, ‘Hi, Orson!’ and I realized the good times were past — the golden time — such a big part of my life and there are so few people alive today who knew him.”

Baxter’s path crossed closely with that of another sacred monster of film, Elizabeth Taylor. He auditioned for and initially booked the part of Octavius Caesar in the first filming of her “Cleopatra,” with beautiful costumes by Oliver Messel, directed by, in his opinion, a great director, Rouben Mamoulian, whom he knew nothing about at the time: “I was so ignorant about everything. I did a test of two scenes, but then Elizabeth had to have her tracheotomy, and the film was shut down.

“Mamoulian sent me a nice letter: ‘My dear Mr. Baxter, I’m too old to wait for Miss Taylor to recover, so I’m resigning. I hope they keep you’ — which they didn’t — ‘You’re a wonderful actor and I wish you well.’”

Baxter finally met Taylor when he made “Ash Wednesday” with her, “and she was just adorable! She was going through a terrible time because Richard [Burton] was there, but not working, and there’s nothing an actor enjoys less than being on a set when he’s got nothing to do with it. And he was drinking, the son of an alcoholic, and he hated everybody on the film except Henry Fonda and me, because like him I was Welsh.

“But when he was drunk he was horrible, not to me, but to her. Henry Fonda got a film and suddenly had to fly to Savannah. So she had to film [her own scenes intensively] and she said, ‘Will you take Richard out to lunch?’ hoping I think, that I would stop him drinking. But you couldn’t. When he was not drunk he was sweet, but otherwise, he was nasty to her, which embarrassed everybody. He was onto drinking a lot of port, which was very strong.

“When I went back to dub the film in Rome, they had split up and she was staying at a hotel. The telephone rang and when she finished it, there were tears in her eyes and she said that was Laurence Harvey’s wife. We knew that Larry had bowel cancer and Patricia was giving him a 45th birthday party. Elizabeth said, “You always said I could stay with you in London. Can I?”

“I knew it wasn’t because of any great affection for me, of course. I knew that she couldn’t stay at the Dorchester Hotel because the press were everywhere chasing out the news about Richard. She took a scheduled flight to London, went to the party, and turned up at my house at 3 a.m. She drank some vodka, but was not drunk at all. I think it was one of the things that drove Richard mad: she could drink him under the table. We talked for about two to three hours, wonderful girl!”

On the controversy over the color of Taylor’s eyes, Baxter was firm: “I arrived for the film [‘Ash Wednesday’] in Cortina and the producer, Dominick Dunne, invited me to dinner. I sat opposite her and Richard, and when she turned to look at me, yes, there were those big violet eyes!”

Regarding Taylor’s acting, he said, “I would rate her as a film star, but I think her performance in ‘A Place in the Sun’ is one of the most extraordinary, beautiful performances — that first shot of her when Montgomery Clift is playing billiards and she looks at him. She was beautiful and so nice, everybody who worked with her loved her, but producers couldn’t bear her because she was always late. But as an actor, she was wonderful.”

Baxter fondly recalled Taylor’s willingness to share the spotlight while making “Ash Wednesday”: “Director Larry Peerce said, ‘Shall we go for a take?’ and suddenly Elizabeth walked across from me, so inevitably the camera was now on me! Peerce said, ‘Did you mean to do that?’ She said, ‘Of course, it’s Keith’s scene. He’s doing the talking.’ Well, I’ve worked with a lot of stars, including Joan Collins, and you would not get that kind of treatment from her. Elizabeth was so generous, funny, and a giggler.”

Baxter never made any bones about being gay:. “Well, I’ve never bothered about it, to tell you the truth. It’s never been something to bother about, really. Maybe that’s the difference between America and London, as the years have gone by. Anybody who knows me knows the focus of my sexuality but it’s not something that one needs to proclaim. I mean, one supports the right issues, of course.

“I think Elizabeth’s speech for AMFAR is simply extraordinary — you can summon it up [on the Internet] — in which she said, ‘Three of my best friends, who I worked with, were gay: Rock Hudson, James Dean, and Monty Clift.’ There was an outcry about Dean, but she didn’t do it for any other reason than to say, “Why would I be prejudiced?’”

I had to ask Baxter, who freely admits to 83 and seems at least 40 years younger in every way, what is his secret. “Don’t play football with your 15-year-old godson or you’ll rip your Achilles tendon. But my secret is not thinking about anything, really.”