On the busiest day of the week in the midst of a worsening coronavirus crisis, Darrell Wimbush arrives at work in the mid-afternoon and prepares for a daunting evening ahead.

Wimbush works in multiple capacities at New Alternatives, an organization that provides services for LGBTQ homeless youth including case management, programs for HIV-positive youth, life skills, and more. The crisis has placed new and unforeseen burdens on service providers like New Alternatives that are continuing to step up with in-person offerings — especially meals for individuals facing food insecurity — in a city where such services have dwindled since many service providers were forced to abruptly shut their doors and shift to remote operations in an effort to promote social distancing and prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

New Alternatives already offered meals to those in need, but Wimbush, who normally carries out security-related duties in addition to cooking, started noticing an uptick in demand in recent weeks and found himself standing at the front lines in the fight to absorb it.

“I’m hearing from multiple clients that a lot of places are closing down that they usually go to during the day,” Wimbush explained. “I’m usually at work four days a week. Now I’m working every day.”

For the time being, Wimbush dedicates one day per week to cooking and preparing food for dozens of clients per day, though he said it is possible he will soon have to start cooking twice per week to keep up with demand. The organization’s food offerings also include a Sunday dinner, which tends to feed anywhere between 50 and 80 clients during normal times.

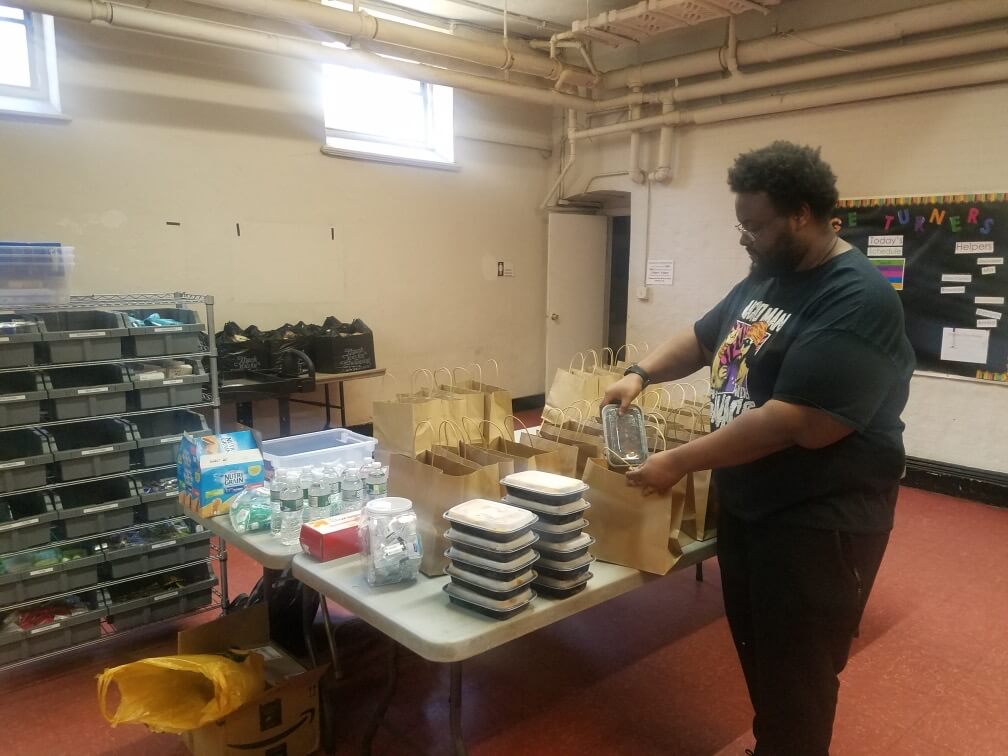

Notably, Wimbush is playing a remarkably crucial role in one the most important areas of the crisis: He alone is responsible for cooking, preparing, and handing out food to numerous clients who are most at need. In short, the food security of countless clients remains in his hands — and he is handling that pressure with seeming ease.

“I’ve been offered volunteers and co-workers have asked for help, but I’ve done this many times,” Wimbush said, referring to his previous work experience that entailed cooking for large groups. “I’m used to cooking for 200-plus people. So I wouldn’t really need any help.”

On a cooking day in the coronavirus era, Wimbush arrives at New Alternatives’ location at Metro Baptist Church at 410 West 40th Street in Manhattan at 2 p.m. and begins removing food from the freezer to be prepared and heated up for distribution to clients. He also organizes toiletry items for distribution, but those goods, too, are in shorter supply, marking yet another sign of the times. Previously, clients were able to choose between different toiletry options, but not for now.

From 3 p.m. until 6 p.m., Wimbush hands out food to clients while simultaneously finding time to engage with them and ask about their day, about their health, and about their lives, adding an extra element to the experience that could make all the difference for those who are confronted with significant stressors stemming from the crisis.

Wimbush allows the scene to wind down from 6 p.m. until 6:30 p.m., at which point he enters the commercial kitchen at the church — complete with two large hot stoves, a griddle, two ovens, and two sinks — to begin cooking and preparing future meals. Two weeks ago he cooked lemonade fried chicken with rice and cabbage, and last week he cooked baked ziti, among other items.

“That goes until 1 or 3 a.m.,” Wimbush said.

Do the math and that workload represents between six-and-a-half and eight-and-a-half hours in the kitchen — all of which comes after food is distributed.

The food he prepares is provided from multiple sources, with most of it being donated. The organization also received some food donations from restaurants during the earliest days of the crisis when they were trying to quickly get rid of food before it expired. Wimbush does make some trips to supermarkets for certain necessities, such as meat.

Wimbush’s dedication to his work means he, too, is risking his health to serve others at a time when many people worldwide have retreated from public life to avoid getting sick. He works with gloves and masks and makes sure he sufficiently washes his hands and food to protect himself and others.

Like everyone else, Wimbush realizes that the future is uncertain. Nobody really knows when the crisis will fade away — and the increased demand at organizations like New Alternatives will only grow as health and economic woes continue to put a strain on the five boroughs. But regardless of how it shapes up, Wimbush is up to the task.

“It’s not as hard as it sounds,” he said. “My higher-ups have asked if anything is needed or if I need a break or extra help. It’s nothing but support from everybody at my job and the church.”