Harm reduction counseling empowers drug users to take control of their health and provides support to individuals who are told that only losers use meth.

Getting high is a natural desire and occurs in virtually every culture; it doesn’t have to be associated with escaping the problems of real life. That 1960s belief persists among some anti-drug warriors, but public health practitioners prefer the more pragmatic conclusion: drug use is a constant and the sensible premise for policy is “How do we live with it?” Criminalizing use heightens health risks, demoralizes users, and is contrary to basic human rights.

This coming month will be a test for these competing philosophies. A special session of the United Nations General Assembly on April 19 will debate drug prohibition as international opinion moves away from prohibition.

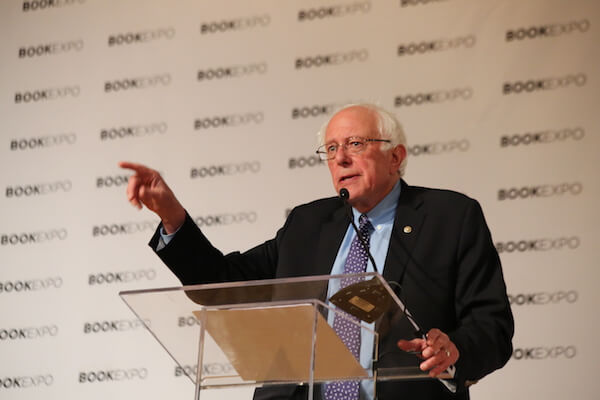

The debate is muted in the United States, at least among elected officials. Bernie Sanders avoids the issue, as does Mayor Bill de Blasio. But the rigidity of the anti-drug opposition is receding. In New York City, harm reduction counseling will be offered to meth users. The San Francisco AIDS Foundation offers these services in its Stonewall Project. Those curious about harm reduction approaches can check out tweaker.org and the Speed Project at new.sfaf.org/tspsf.

While some people try meth and stop, others don’t. Programs are needed for those who have the habit. So it is good news that the city is playing catch up by funding a collaborative program of clinical and community-based services to “help people who use methamphetamine mange or reduce their use.” The objective is to reduce harms associated with meth — especially transmission of HIV, STDs, and hepatitis C.

This is one among 10 programs sponsored by New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene as it implements the New York State Blueprint on Ending the Epidemic. Other city programs help individuals who have stopped using meth stay off it.

The images of death and decay surrounding meth interfere with users’ choices. The message that the chemicals in meth alter the brain and create dependency may leave users hopeless, saying “The drug is destroying me. What does it matter what I do?” This pessimism can escalate risky behaviors. Harm reduction counseling offers ways out of this trap.

Drug use, even meth, comes in three types: use, abuse, and dependency. Distinguishing these types helps people realize they can still control their life. Use means a person tweaks over a weekend with friends, goes to work, and the rest of their life stays intact. Meth is an illegal substance, and there are risks associated with products produced by outlaws, but a person who goes on with their life after doing meth is simply a user.

Not all meth use, of course, has such a benign course. After a person tries crystal and discovers it rocks their world, increases concentration, gives great energy, and heightens sexual arousal, then watch out. Those ebullient feelings cannot be reproduced by constant use.

Abuse can be a four-day bender. What happens next is crucial for a person’s health. Abuse can be an attempt to manage use, if it is followed by abstinence. If the binge costs a person a job then a person is not managing their use. Dependency is different; it’s the belief that a person must have the drug. Often the dependency is accompanied by physical pain, depression, and anxiety.

Prohibitionist ideology errs by emphasizing a lock step movement from use to dependency. This is a terrible thing to tell a user. Equally problematical is the absolutist reliance on a 12-Step response — I am powerless before meth (alcohol, food, heroin, take your pick). For some people, a 12-Step program works; others may need rehab. But each person must find their own way of handling habitual use or dependency.

Addiction is related to dependency but it occurs when a person’s life is harmed: performance on the job declines, friends are lost, intimate relations are impaired. William S. Burroughs, the novelist, depended on heroin, but kept at his profession and turned his habit into an aspect of his charm. Few of us have Burroughs’ wealth, which enabled his life. Still, his example illustrates how meth users can take steps to improve their health and happiness even if they use the drug.

Dependency and addiction are not peculiar to drugs, and harm reduction questions the theory that the chemical properties of drugs provide an adequate explanation for addiction. Gambling has no chemical properties, but it certainly leads to addiction; ditto for shopping, eating, or video games. Getting addicted doesn’t mean a person is a loser or has become one. It’s a problem that people from all walks of life confront. Harm reduction helps people make adjustments. It offers hope and doesn’t start by demanding abstinence.