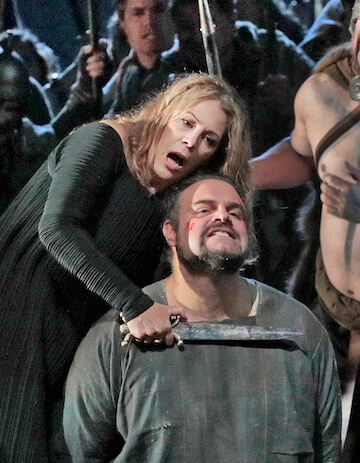

Sondara Radvanovsky and Joseph Calleja Sir David McVicar’s Met Opera production of Vincenzo Bellini’s “Norma.” | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Vincenzo Bellini’s “Norma” is considered the summit of bel canto, a masterpiece that inspired Wagner and Schopenhauer. Felice Romani’s libretto and Bellini’s music elevate the character of Norma to profound tragedy, the Medea-like druid priestess’ vengeful fury transformed into sublime self-sacrifice in the opera’s finale.

Too often, however, hacks are put in charge of the direction and conducting. Bellini’s “Norma” brings out the worst in stage directors. The opera’s Romantic era vision of ancient Gaul usually results in tacky kitsch — pâpier-maché rocks, serried rows of druid choristers in fake beards and baggy robes, and a routinier beating time in the pit. (Lately, though, directors have been getting more creative as in the recent Salzburg production that reset the story in World War II occupied France.)

The Metropolitan Opera opened its 2017-2018 season with a stirring new production of Bellini’s “Norma” starring Sondra Radvanovsky (replacing the originally scheduled Anna Netrebko). Sir David McVicar’s production takes the story seriously while retaining the original locations and time period in Romani’s libretto. McVicar humanized the characters, giving them specific and surprising individualized stage business that steered clear of “park and bark.” In the duet “In mia man alfin tu sei,” Norma threatens the life of Adalgisa if the captured Pollione does not renounce her, but Pollione defies Norma. At the duet’s close, Sondra Radvanovsky and Joseph Calleja as the sparring ex-partners stood together closely but each faced in the opposite direction. These former lovers were in direct opposition yet inextricably bound together.

McVicar’s stirring production stars Radvanovsky, Calleja, DiDonato

McVicar employed his usual cadre of musclebound male extras portraying druid warriors, emphasizing the story’s wartime setting, and he stressed personal drama over political or religious commentary. We were in ancient Gaul, but this was a real place with real people.

Robert Jones’ stark scenery and Moritz Junge’s goth costumes evoked “Game of Thrones” with fog-bound forests and barbarian-chic costumes with hip contemporary details. The sets and costumes emphasize tones of black and gray with bright blue and red accents. Jones’ set design wisely utilized the Met’s stage elevator, resulting in seamless scene changes with no stage waits. Norma’s woven hut dwelling with its domed ceiling was full of practical domestic objects. Paule Constable’s lighting emphasized striking chiaroscuro effects, but did every scene have to take place late at night? Couldn’t Act I and II begin at dusk and end at night?

Of course, “Norma” is a singer’s opera — no matter how good the production is, the evening’s success depends on a virtuoso trio of leading singers. The singers the Metropolitan Opera provided were less than perfectly cast and vocally uneven. Yet the performance as a whole was greater than the sum of their individual vocal merits and flaws.

The choral and orchestral forces were in strong form. Carlo Rizzi’s conducting had admirable energy, control, and forward momentum, but lacked a spiritual quality. The Met utilized the autograph score opening cuts in the “Ah, Rimembranza!” duet and the “Oh, non tremare, o perfido!” trio that Richard Bonynge also restored in his first “Norma” recording with Sutherland and Horne. Elsewhere, arbitrary cuts were made seemingly to spare the singers rather than for musicological reasons (such as with the second half of Pollione’s “Mi protegge, mi difende” cabaletta).

Matthew Rose’s rough-hewn Oroveso was more barbaric warrior chieftain than noble high priest in costume and vocal manner. Michelle Bradley’s Clotilde was sung with a strikingly rich timbre and seemed to have more at stake in the story than usual. Calleja, usually heard in more lyrical tenor roles, was an unorthodox sounding Pollione. The low declamatory phrases in “Meco all’altar di Venere” pushed the Maltese tenor’s delicate vibrato into a full-scale bleat, and the attempted high C was weak and covered. The Act I duet with Adalgisa allowed the honey to flow back into Calleja’s tone and he delivered some shapely, stylish phrasing. He shed his stiff manner in his final confrontation with Norma in Act II, singing and acting with honesty and power.

Unlike Radvanovsky or Calleja, Joyce DiDonato is a natural stage animal. Her Adalgisa benefited the most from McVicar’s direction. Adalgisa appears onstage assisting Norma in the ritual during “Casta Diva” (as a novice priestess she has to be there). DiDonato under McVicar’s guidance projected an intensely personal conception of the character: a vulnerable, impressionable young woman torn between two powerful personalities locked in deadly personal conflict. Her slender silvery mezzo sounded more youthful than Radvanovsky’s darker, hooded soprano, which is dramatically apposite.

But Adalgisa was composed as a soprano role and DiDonato’s top was stretched beyond its limit too often, turning quavery and white-toned. In the fast section “Ah! Sì, fa core e abbracciami” of the Norma/ Adalgisa Act I extended duet, she rewrote the vocal line to duck a high C that Norma had sung measures before in the identical phrase. DiDonato’s rhythmically precise coloratura and intensely expressive diction highlighted deficiencies in those respects in Radvanovsky’s Norma.

Radvanovsky returned to the role she sang in the previous (kitschy, ugly) John Copley production in 2013 and has performed around the world many times since. On October 3, Radvanovsky sang with technical resourcefulness confronting all the difficulties the score throws at her. Radvanovsky displayed many of the same strengths (wide vocal range, steely power, fearless attack) and too many of the same weaknesses (lack of tonal beauty in lyrical legato phrases, mushy Italian diction, and uneven vibrato) as in her previous assumption. There was a loss of control in fast coloratura sections (“Ah! bello a me ritorna”), and her disembodied pianissimos were sung off the breath, turning tremulous and pitchy.

As in 2013, Radvanovsky stressed the suffering, betrayed woman in Norma over the hell-hath-no-fury Medea-like priestess — I never feared for her two little boys or Adalgisa or Pollione in Act II. However, her rather ordinary, unhappy, abandoned woman actually suits McVicar’s humanized conception extremely well.

My biggest reservation was about her projection of text — when the music gets hard and intense (which it constantly does in “Norma”) — Radvanovsky stresses tone over text, which will recede into the musical line. Phrases like Norma’s searing “Nel suo cor ti vo’ ferire!” (“I’ll strike at your heart through hers…”), which Callas snarls like a tigress in various recordings from the 1950s, was sung matter of factly by Radvanovsky. In the final scene depicting Norma’s self-sacrifice with Pollione joining her in death, Radvanovsky and Calleja rose above their dramatic limitations and vocal miscasting. The fire of Bellini’s — and Romani’s — genius glowed bright.