Van Sant’s look at school slaughter is triumph of naturalism

“Elephant,” an unsettling and thoroughly spellbinding new film from director Gus Van Sant, takes its name from the ancient parable of the blind men and the elephant. In the story, several blind men examine different parts of an elephant, and each man becomes convinced he understands the true nature of the animal based on the single part—tail, leg, tusk, ear, knee—he touched.

Consequently, one man insists the elephant is built just like a rope. Another says it’s more like a tree, another claims it’s like a spear, and so on. All are partially correct, but, since none has a clear picture of the entire animal, they’re each actually more wrong than right.

The beast under inspection in “Elephant” is school violence—Columbine-style shootings, to be exact. Van Sant, ever the provocateur, takes a distinctly different approach to his subject matter than countless filmmakers before him, who, throughout cinematic history, have tackled this and myriad other social problems in an obligatory cause-and-effect fashion.

By contrast, Van Sant, having clearly taken the moral of his titular parable to heart, resolutely refuses to attempt to sum up the problem of school shootings. Nor does he offer explanations for any of the behavior depicted within his film. The events, which unfold in a deceptively dreamlike manner, are presented strictly as-is.

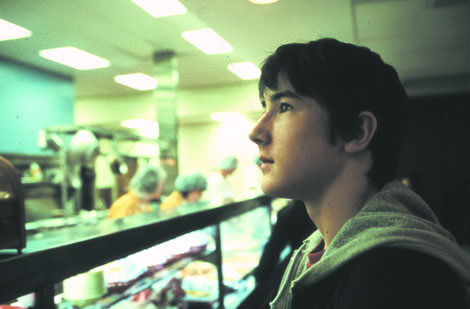

Van Sant took top prize at the Cannes Film Festival for his work here, and deservedly so. Picking up where his artfully experimental “Gerry” left off, “Elephant” features partially improvised performances by non-professional teenaged actors and truly mesmerizing cinematography. But the film’s most appealing attribute is an especially brilliant structure that ignores linear conventions and instead allows viewers to see events from multiple perspectives. Artfully dissecting the manner in which the students’ lives intersect—or nearly intersect—within their unexceptional microcosmos, Van Sant skips forward and backward in time so deftly that, in many cases, we aren’t even immediately aware it’s happened.

This is made possible by a camera that seems to never stop moving. In hypnotic fashion, it circles, follows, traces, and wanders, ever so slowly, from subject to subject, perspective to perspective, lulling viewers into a dreamlike state.

The fact that the action it’s following is, in all but a few cases, little more than the commonplace activities of typical high school students only adds to the deceivingly soothing tone. We are introduced to the students in no particular order of importance. They include a sweet but overburdened slacker, a frumpy nerd, a genial gay photographer, a trio of cool girls, and the school’s reigning heartthrob.

We see these students as they navigate the seemingly endless array of classrooms, corridors, passageways, gymnasiums, cafeterias, common areas, locker rooms, athletic fields, and parking lots of their high school. We hear snippets of conversations—trivial exchanges about parents and boyfriends and concerts and such. A dialogue that appears in the foreground of one scene will recur as little more than a murmur in the background of another. Long stretches of the film have no dialogue at all; the only noise emanating from the screen a chaotic, hiccuping miasma of manipulated sound samples, jazz riffs, and space-age noise effects.

We are also introduced to a pair of outcasts. Despite the malevolent intentions we soon learn they harbor, their day, too, unfolds in an almost comically mundane manner. Passing time on what they expect to be the last afternoon of their lives, they sleep, hone their shooting skills first on a video game and then with a recently purchased weapon, play piano, and, notably, share a kiss and a shower.

This awkward act of intimacy doesn’t suggest that the two are necessarily gay. Rather, it comes across as an attempt by two confused, lonely boys to experience an emotional connection with another person; an item to cross off their “To Do” list before they die. In that clumsy moment, we witness their humanity, if only briefly, before they fully evolve into the monsters they’re intent on becoming.

As the story heads, mercilessly, toward its inexorable conclusion, the camera’s measured pace and detached manner begin to feel overwhelmingly menacing. The lives of the students crisscross in the same ways they have day in and day out for weeks, or even years. But for viewers, knowing that this ordinary day will be cut short by an act of such extraordinary violence becomes a burden almost too painful to bear.

Compelling, naturalistic performances by everyone involved, combined with the incredibly deliberate pacing, create an atmosphere that is at once hyper-realistic and utterly ethereal, a quality enhanced by a soundtrack composed of musique concrete, a form of electronic music developed in the 1940s and based on natural sounds rather than conventional instruments. The effect is overwhelmingly hypnotic, by design. By lulling viewers into a complacent trance before hitting them over the head, Van Sant skillfully heightens dramatic tension.

The ever-changing perspective reminds us that, for each of the students, school is a markedly different experience. Moreover, it demonstrates that, as in all matters, “ordinary” is in the eye of the beholder.