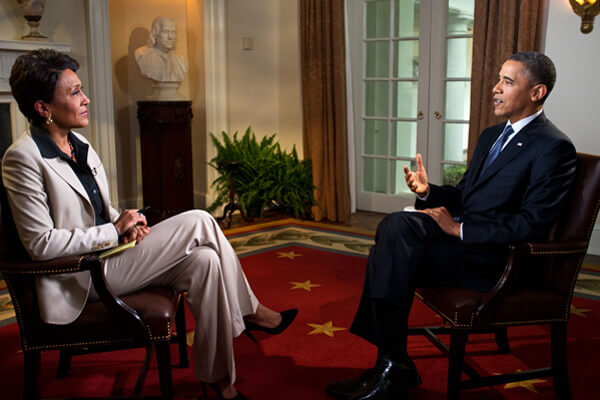

Joseph Vitale and Robert Talmas in their Manhattan home, with their son Cooper, who just celebrated his first birthday. | GAY CITY NEWS

BY PAUL SCHINDLER | It was only in the immediate aftermath of finalizing the adoption of their infant son, Cooper, on January 17 of this year that Joseph Vitale and Robert Talmas became aware that a significant — and unwelcome — legal hurdle lay ahead.

Nine months earlier, the two men, who live in Manhattan and married in September 2011, on the 15th anniversary of becoming a couple, spent the legally required 72 hours in Ohio so they could adopt Cooper, at the time he was born, from the birth mother with whom an adoption agency had made them a match.

The woman originally said she did not want to meet the adoptive parents, but when Vitale and Talmas arrived in Cincinnati for Cooper’s birth, they learned she had changed her mind. They were told to meet Cooper’s birth mother at a local Catholic hospital.

Married Manhattan men win marriage recognition order in federal court, soldier on

“I thought, ‘We’re finished,’” Talmas recently recalled, explaining the two dads expected to encounter hostility in a Catholic institution. Instead, the hospital welcomed them, giving them a room close to Cooper’s birth mother for the three-day waiting period.

“They couldn’t do enough for us,” Talmas said.

The two men looked on Ohio as an attractive venue for adopting their child. In some states, Vitale noted, only one of the men could have adopted, and the other would have to do a second-parent adoption in New York. But Ohio provisionally released Cooper in their care, and the men were able to formalize the adoption in a New York City courtroom.

The adoption decree granted here included a directive that a new birth certificate be issued naming Vitale and Talmas as Cooper’s parents.

Much to the couple’s chagrin, they quickly learned no such certificate would be forthcoming from the State of Ohio. Their first instinct was anger — directed at their attorney and their adoption agency. Why had no one anticipated this problem or alerted them to its potential?

It soon became clear, though, that the obstacle they faced was of recent political vintage — January 2011, to be specific. After Republican Governor John Kasich and Attorney General Mike DeWine took office that month, they ordered the State Department of Health to overturn existing policy that would have allowed Vitale and Talmas to obtain the birth certificate they wanted. The state’s two top officials took the position that Ohio’s ban on same-sex marriage and recognition of such marriages from out of state prevented the issuance of a birth certificate naming them as Cooper’s legal parents.

The absurdity of the Republican officials’ argument was not lost on the couple.

“The real hook was when they said they were not recognizing our marriage,” Talmas said. “But this wasn’t a gay marriage case. This was about recognizing a New York adoption order.”

The couple’s ability to adopt Cooper in New York had nothing to do with their being married; they could have gone ahead with it even if they were still unmarried. All Ohio was being asked to recognize was the validity of an adoption granted in a New York State courtroom. But Vitale and Talmas also recognized the “political platform” Kasich and DeWine had jumped onto in order to appease their conservative GOP base. The battle to get a proper birth certificate for Cooper would be one waged over the issue of gay marriage.

But it was also about a lot more than legal arguments and political posturing. For the two Manhattan men, it was very personal, and at each step of the way it is Cooper that has been at the center of their concerns.

“We wanted a document that reflects who our child’s parents are,” Vitale said.

His husband added, “I appreciate the arguments about our civil rights, but it’s really about Cooper’s civil rights. The State of Ohio was not taking care of — to me — one of their children, a child who was born there.”

Leaving aside the potential harm Cooper could face if only one of his dads were on his birth certificate — particularly if the family were outside New York and an emergency arose — there was the deeply emotional question of which father’s name would appear and which wouldn’t.

“Later in life, we would have to have a conversation about why we’re not both on the birth certificate,” Talmas said. “Who wants to have that conversation?”

For Talmas, projecting what emotions arise in a family in the context of adoption is not idle speculation. He himself is an adopted son and speaks with unabashed happiness about his life growing up — an experience that made him eager to become an adoptive father himself.

Ironically, though, something he encountered as he and Vitale worked on Cooper’s adoption reminded him of how the questioning of one’s parentage can sting, even coming decades into adulthood. As part of the paperwork required in Cooper’s New York proceedings, each man needed multiple copies of their own birth certificates affixed with raised official seals. Knowing he was born in Nassau County, Talmas traveled to the clerk’s office there to obtain what he needed. But he faced a bewildered county employee trying to figure out why there was no record of his birth, asking first if he had ever changed his name and only later if he was adopted — as a growing line of impatient people waited their turn behind him.

Because his adoption was “closed,” the birth certificate had been forwarded from Nassau County to Albany, and in time Talmas got his hands on what he needed. But months later, when the issue of his own son’s birth certificate surfaced, he immediately told his husband, “Joe, I will never take one with just one name.”

Fortunately for the two dads, their adoption agency immediately recognized the risks posed to prospective clients from Ohio’s new posture toward issuing birth certificates to same-sex parents. Vitale and Talmas learned of a lawsuit in the works challenging the policy by taking on the state’s refusal to recognize valid same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions.

Late last year, US District Court Judge Timothy S. Black struck down the ban on recognizing such marriages in the narrow context of recording marital status and surviving spouses on death certificates. Vitale and Talmas joined three other couples whose challenge to the recognition ban as it applies to birth certificates was heard a few months later, by Black as well.

Unlike Vitale and Talmas, the other three plaintiff couples live in Ohio and they are all women. Each is expecting a child in the next few months, conceived through donor insemination. The lesbian couples, all married outside of Ohio, want these births to be treated the same way the state treats births to different-sex married couples when the wife becomes pregnant through donor insemination— with the state automatically issuing a birth certificate identifying the mother’s spouse as the child’s other legal parent.

The two Manhattan men did not at first grasp why their joining the case was particularly alarming to Ohio officials. The lawsuit overall posed the issue of whether the state violated the plaintiffs’ federal constitutional rights by refusing to recognize marriages that were legal where they were celebrated — still very much an unsettled legal question.

Vitale and Talmas brought an additional argument to the table — whether under the Constitution’s Full Faith and Credit Clause, Ohio could refuse to honor an adoption decree from another state. The Constitution’s Full Faith and Credit Clause is not seen as extending to the recognition of marriage, but it does generally require that court orders — which an adoption is, but a marriage is not — be honored from one state to another.

In fact, when Black, on April 14, ruled in favor of the four plaintiff couples on the question of marriage recognition, he noted in a footnote that Vitale and Talmas also had an avenue of redress based on the Full Faith and Credit Clause.

Black’s ruling in the birth certificate case went well beyond his decision in the death certificate matter, finding that Ohio’s refusal to recognize legal out of state marriages was unconstitutional in all instances. Two days later, the judge bowed to reality — namely, the Supreme Court’s January order that the Utah marriage equality ruling be put on hold until all appeals are exhausted — by staying his order, except as it applied to the four plaintiff couples.

For Vitale and Talmas, the pace of events suddenly shifted into high gear. Within five days, the couple had an emailed copy of Cooper’s birth certificate on their smart phones, something that clearly buoyed their spirits when it arrived just moments before they sat down with Gay City News. The form still had a space for “Mother’s Name” and had both of their names under the header “Father’s Name,” and they were not buying the state’s explanation there simply had not been time to revamp the form. They knew that Kasich and De-Wine were not yet willing to wave that white flag.

In the days since then, the couple has struggled over whether or not to accept a form also compromised by the fact that it is stamped with the words: “Note: Pursuant to United States District Court, Southern District of Ohio — Case No. 1:14-cv-129. Issued April 14, 2014. “

As Vitale put it in an April 29 email, “Don’t want a footnoted Birth Certificate.”

Regardless of whether or not they take the piece of paper the State of Ohio is now offering, the couple is in it for the long haul. If Ohio prevails in its appeal of Black’s order, it could conceivably withdraw even the footnoted document.

Vitale and Talmas estimate that their adoption of Cooper cost them close to $40,000 and said that the effort to battle the denial of his birth certificate has added another 25 percent or so onto that — largely in last-minute trips to Ohio for court proceedings.

“Now we’ve become activists,” Vitale said, noting that so far the expenses are manageable, but might not be for everyone faced with their dilemma.

He added, “We haven’t abandoned Ohio. It’s where Cooper is from.”