God’s Love We Deliver recently took this reporter on a tour of its new building at Sixth Avenue and Spring Street, offering a look at the place’s interior –– and in particular the nonprofit’s high-volume, health-conscious cooking operation that sustains thousands of seriously ill people each week.

The $28 million project — completed in a year and a half — has transformed GLWD’s former headquarters, a squat, two-story, 60-year-old building, into a new five-story facility, more than doubling its space to 48,000 square feet.

In addition to its boosted height, the new building’s shiny aluminum cladding certainly makes it hard to miss. Originally a library for the blind, the former building was nondescript, and, when viewed from the outside, gave little sense of what went on inside. The new headquarters boasts large windows that both let in light and allow people to see what’s going on inside.

After pitched battle over air rights sale, luxury development, group feeding those seriously ill back in Soho

“In our redesign, we wanted to let people from the outside know who we are,” said Karen Pearl, the organization’s president and CEO. “Before, with our little brick building, you couldn’t see what we were doing.”

Similarly, increasing the sense of openness, the new entryway sports a staircase on the corner offering access from both Sixth Avenue and Spring Street.

Not far from the front doors, in an area with slightly chilled air, volunteers were doing “meal packaging and kitting,” as Pearl explained. Each bag contained either regular food, modified food, or individually prepared food, per each client’s needs. For example, some meals are pureed for people who can’t chew.

Adjacent to this area is the vehicle bay on Spring Street, which is now enclosed, where the GLWD vans pick up the food for delivery.

The group hopes that the building will achieve a LEED Silver energy-efficient designation. In that vein, Pearl pointed out numerous bike racks lining the bay’s walls. For the benefit of volunteers and employees who bike, there are showers in the basement to wash off the sweat.

On the second floor is the hub and heart of GLWD — its new 10,000-square-foot kitchen. In spots along the walls are memorial and honor tiles that once adorned the former kitchen. Those with red hearts honor individuals who have passed on.

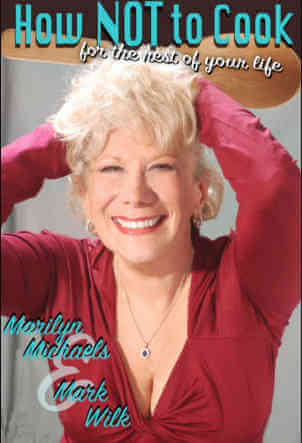

Running things in the Joan Rivers Bakery is Chuck Piekarski, a GLWD employee. His post there was clearly meant to be, as he noted, since in Polish his last name actually means “son of a baker.”

The late comic Rivers was a longtime God’s Love supporter.

“The nice thing is Joan knew she was going to be honored with the bakery before she passed away,” noted David Ludwigson, the group’s chief development officer.

In a light-filled corner of the bakery, a group of regular volunteers — they have all volunteered there for about five years, two to three times a week — were scooping dollops of low-sugar / low-fat cranberry scone dough into individual tin containers. Three hundred of these were loaded onto trays, which were then put onto a tall cart, which was wheeled into a high-tech, man-size oven to cook, after which they would be flash-frozen.

“It’s so much safer for the food,” Pearl noted of the freezing method, which God’s Love has used since 2013.

“Everything that leaves here is frozen or chilled. Clients like the chilled-food model — they can eat what and when they want.”

It’s all a streamlined operation. Some time ago, Piekarski realized that cracking hundreds of eggs each day was too time consuming. So he now uses liquid egg yolks instead that he buys by the quart.

“When you cook 5,000 meals a day, you learn about efficiency,” Pearl explained.

Nearby, another employee was mixing soup in big 60-gallon vats — vegetable bean or beef minestrone.

Eighty-five staff and 8,000 volunteers keep GLWD running.

All of the meals are provided to the clients for free.

God’s Love started in 1985 as the AIDS crisis was gripping New York, advocating the concept of “food as medicine.” Fifteen years ago, the organization shifted its mission, and now provides meals to seriously ill people with any of 200 different diagnoses, including HIV/ AIDS, cancer, heart disease, and renal failure, plus Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and multiple sclerosis.

Children of sick individuals also get free meals, since people who can’t cook for themselves can’t do it for their kids.

Half of the clients get frozen meals delivered twice a week — with each delivery covering the meals for half the week — while the other half opt for all the meals to be delivered on one day each week.

GLWD doesn’t fry food, and no preservatives, additives, or artificial flavors or colors are used.

“We have to be extra careful with food because our clients’ immune systems are compromised,” she noted.

The kitchen gets cleaned three times a day, and everyone around the food has to wear a hair net or hat.

The group hopes to soon add a digester, which will break down any leftover food by using enzymes, after which the waste can then be poured right into the sewer.

The third and fourth floors include office space for GLWD staff and areas for volunteers to gather. The fifth floor features a large communal education space with a demonstration kitchen, which will be used for teaching and donor events. Setbacks at the fifth-floor level have been used for terraces, with outdoor seating for volunteers and others to relax before or after their shifts.

Finally, on the rooftop is a sweet-smelling, thriving garden featuring basil, mint, rosemary, bronze fennel, lemongrass, thyme, sorrel, dill, and more — all potential ingredients for the food. Recently, the mint had been included in iced tea and the basil in a marinara sauce.

“The lemongrass was used to make a great lemongrass broth,” noted Emmett Findley, God’s Love’s manager of communications.

In a unique arrangement, the GLWD building’s rooftop is technically accessible to future residents of the new luxury residential high-rise being built just to the north.

“There actually aren’t that many apartments in there, so we don’t think a lot will come up here,” Pearl predicted.

Allowing the open-space access to the rooftop let the developers extend their building farther toward GLWD than the zoning normally would have allowed, she said.

Helping finance its own project — but raising neighbors’ ire — GLWD sold $6 million worth of air rights to that adjacent development. Neighbors who opposed both projects protested that because the deed restriction on the God’s Love property mandates community use, the development rights could not be transferred for a private, market-rate use.

However, Pearl said, “There’s actually not anything that was not done 100 percent according to building code. A lot of nonprofits are selling air rights. We could have built apartments on top but we didn’t.”

Plus, she added, “The air rights were not addressed in the deed.”

More to the point, she said, the air rights sale allowed God’s Love to build its great new building.

During the construction, GLWD moved its operations to South Williamsburg and paid rent, which added to the project’s overall cost. Some Soho residents no doubt would have preferred that the organization simply relocate there, rather than build a new HQ whose design and materials, they charge, are not contextual with the surrounding area.

But Soho is where God’s Love owned its property, and Soho is where it will now continue operating in its new state-of-the-art building, which its leaders are confident will allow it to better fulfill its mission of helping the severely ill through healthy food.