Nellie McKay was Billy Tipton for three nights at 54 Below. | DAVID NOH

One of the great enigmas in the music world, William Lee “Billy” Tipton (1914 – 1989) was an American jazz musician and bandleader, who, it was discovered after his death, was born a woman. Named Dorothy Louise Tipton at birth in Oklahoma, he took his father’s name, “Billy,” when he started his music career and bound his breasts and stuffed his pants to pass when he performed. By 1940, he was living as a man in private as well as public life, and no one, apart from a couple of cousins and perhaps his lovers, knew his secret. He toured the country with different bands, eventually forming the Billy Tipton Trio, which was signed by Tops Records in 1957 and recorded two moderately successful albums.

The band was offered a permanent position at a Reno hotel and more Tops recordings, but Tipton decided to move to Spokane, Washington, to work as a talent broker and lead his trio as a local club’s house band. He had many paramours, but the chief one was a stripper named Kitty Kelly with whom he adopted three sons. They split up and he took custody of the boys, moving into a mobile home and living in poverty. By the late 1970s, arthritis forced him into retirement from music, and in 1989 he died from a hemorrhaging ulcer.

One of his sons, William, only realized at the hospital that his father remained biologically a woman, and the coroner agreed to keep this a secret. After financial offers from a curious media, however, Kitty went public and the story broke the day after Tipton’s funeral.

On August 7, Nellie McKay debuted her show, “A Girl Named Bill — The Life and Times of Billy Tipton,” at 54 Below, and I venture to say the weekend run was the artistic highlight of the summer. I have long suspected McKay of being a real genius and this engagement proved it in spades. She’s tackled onstage biography before, as in her salutes to Rachel Carson and Barbara Graham, but this was her most lucid, comprehensive, and fully committed portrayal yet. With just a few props, some costume changes — including the dazzling switch from demure, cloche-hatted Dorothy to ebullient, be-suited Billy with a brunette man’s haircut — and the acting help of her totally game backup trio, she painted a thrillingly theatrical, musically divine, full-scale portrait of Tipton, filling in puzzling blanks with the kind of empathy that only a true artist can muster.

The records I have heard of Tipton reveal a pleasant piano technique, with nothing like the dazzling virtuosity McKay always shows off with such careless ease, and the song selection was brilliant. McKay is a true old movie lover and she included two enchanting selections from classic Ernst Lubitsch comedies. “Jazz Up Your Lingerie,” delightfully warbled originally by Claudette Colbert and Miriam Hopkins in “The Smiling Lieutenant” became a witty commentary about cross-dressing, and “Trouble in Paradise,” complete with perfect mandolin accompaniment, was pure Paramount 1932, with its campy overripe romanticism.

There were nods to all the great studios, starting with Fox with that charmer “But Definitely,” written by Harry Revel and Mack Gordon for Shirley Temple. MGM then took over with “Tira Lira La,” from the filmization of “I Married An Angel,” and McKay and Co. invested this deliriously delicious ditty with an overload of winking fun. Finally, her “Knock on Wood” magically turned the club into Warner Brothers’ Rick’s Café, as she effervescently performed that Dooley Wilson gem from “Casablanca.”

Palpable and contagious was McKay’s delight in singing such male anthems as “The Sadder But Wiser Girl” and, especially, the noxious “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man,” while the walls of 54 Below positively turned blue with Jelly Morton’s “Winin’ Boy Blues” (“I had that bitch and had her on the stump,/ I fucked her ‘til her pussy stunk/ I’m the winin’ boy, don’t deny my name”). To hear those lyrics sung by a woman, even in drag, was liberating, to say the least.

Making no attempt to really enact a man, McKay retained her familiar sunny persona as Billy, which worked beautifully, telling wonderfully awful jokes with a “Ladies, please!” refrain and reveling in impersonations of Elvis, Liberace, and, smashingly, Jimmy Durante doing “Inka Dinka Doo.”

It wasn’t all jovial high-jinks, however, for she gave the loveliest reading of “The Nearness of You” I have ever heard and, later, during Tipton’s darker passages, conveyed the terror of being stopped in the Deep South with her black musician by a bigoted cop, followed by the “Broadway Danny Rose” desperation of her time as a talent manager and her impoverished later years, marked by illness. This went way beyond the kind of joshing if diabolically clever playacting she has done in the past, bringing a real ear to the eye; hell, she even dropped dead on the stage. I really hope she revives this insanely wonderful, important show in some way, shape, or form, so our entire community can experience it.

Every bit as wonderful was another formidable female on the keyboard, Tori Amos, at her Beacon Theater concert (August 12). I confess to having adored her first three albums back in the 1990s and then letting her fall off my radar for no good reason. She certainly didn’t need me, as a sold-out house of Amos fanatics — a terrifically varied demographic, from dyke couples to Upper West Side middle-aged intellectuals to glitteringly be-garbed gay fanboys — roared their approval at the very first familiar notes of every song she started.

“This will be a whole evening of requests!,” she cried, as she mesmerizingly held the stage solo for two solid hours on two pianos, including her own impressive Bösendorfer, radiating an elegant, warm, grateful, humble aura while showing off flabbergasting sound and imperishably strong vocal technique, all marks of a great artist. Along with everything else, her concert was the most technically impressive and visually beautiful I have ever seen, with immaculate usage of lasers and other lighting effects, glorifying her to a fully deserving goddess stature, superbly timed to the music, with a swoony color palette like that of vintage kimonos — violet and gold at one point suffusing the stage.

Cabaret hound that I am, it had been a while since I’ve been to a big concert — the Beacon was the perfect venue — and it made me recall that there is nothing like the thrill of leaving a fully satisfying evening as this one was amidst a crowd of completely blissed-out New Yorkers, jabbering happily about what they’d just experienced.

McKay and Amos gave me real art. Now for fake art — by which I mean the hotly attended “The Maids,” at City Center (August 10). At this play, you saw the kind of well-heeled Birkin bag-bearing fashionistas you never see at the theater. Why? Cate Blanchett, darling! And as the lights went up on the uber chic white set, with its huge rack of designer clothing, mirrors, and flowers everywhere, you could feel them all settling in for a suitably soignée entertainment.

Although they gave the production the requisite standing O, I wonder how many of them really enjoyed seeing— let alone understood what they had just seen, which was basically an indefatigably vicious attack upon themselves, with dialogue, crudely adapted from Jean Genet, along the incessant lines of “You stupid, gutless, fucking cunt. Put your head back and open your fucking mouth!”

We have Blanchett’s husband, Andrew Upton, and director Benedict Andrews to thank for such classy repartee, and their take on the 1947 play was relentlessly vulgar and in-your-face, empty shock value that went beyond grotesque to being pathetic and embarrassing. Watching Blanchett, Elizabeth Debicki, and, especially, a hyperactive, incomprehensible, anything for a non-existent laugh Isabelle Huppert roll about, scream and spit at each other, and fondle their groins for an interminable 90 minutes was like being stuck in some fresh hell of a playhouse with particularly scatological, sugar-besotted brats in desperate need of Ritalin.

The production was unwisely tricked out with video projections that came perilously close to the actresses’ faces, revealing much more than one needed to know — i.e., the need for a good shave on some of them. If this review seems misogynistic, forgive me. That’s not my intention, and my take is rooted in Genet’s original conception — admittedly hard to take, even when done well. For real misogyny, this production took the cake and left no crumbs. So, please, dear readers, do not beat yourself up if you were unable to score tickets to this one. You dodged a big, smelly bullet.

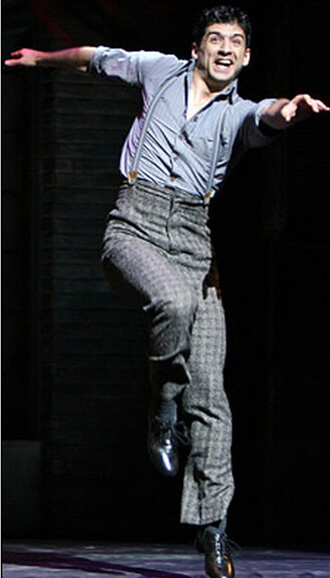

Tony Yazbeck plays Tulsa opposite Patti LuPone as Mama Rose in “Gypsy.” | TONYYAZBECK.NET

Tony Yazbeck’s 54 Below engagement, “The Floor Above Me” (August 14), was, surprisingly for that enclosed space, a dancing affair. By putting his drummer on the floor, the stage widened considerably, enough to give him room to really strut his stuff, which he did, and then some. Homage was paid to Astaire and Kelly, with hyperactive tapping to “Pick Yourself Up,” “No Strings,” “I Won’t Dance” (with sassy Melinda Sullivan), and “Moses Supposes” (with a winning Curtis Holbrook).

Yazbeck landed a job as one of the newsboys in the Tyne Daly revival of “Gypsy” and never looked back, and his reminiscences about his showbiz start were touching, culminating as they did when he played Tulsa in Patti LuPone’s edition of that imperishable show. He performed the signature “All I Need is the Girl,” and is a winning presence, slated to play Gabey in the upcoming “On the Town.” His dancing is far stronger than his singing, and I just wish he had done more with material not so strongly associated with the iconic Astaire. When you hear those Berlin/ Kern gems, old Fred’s urbane image is hard to erase, and Yazbeck could bring real freshness to so many other songs if he chose to, I’m sure.

I’ve got to beat the drum for Ira Sachs’ film, “Love is Strange,” an instant classic. At the beginning, with its reverberations of YasujiroOzu’s “Tokyo Story” and its inspiration in Leo McCarey’s great, heart-rending “Make Way for Tomorrow,” I was seriously fearing this would be Sachs’ “Make Way for Two Homos.” And, of course, one always has some trepidation when famous heteros take major gay roles.

But then you realize that really good actors like John Lithgow and Alfred Molina rise to really good material and their personal sexuality becomes entirely moot. (See Jason Alexander, the only performance I could watch in the film of “Love, Valour, Compassion”) “Love is Strange,” for me, is the opposite of “Brokeback Mountain” –– a gay film made by a gay man, deserving of every accolade, which rings with authenticity, sometimes excruciatingly, sometimes radiantly.

And it’s beyond gay. It’s a good film, period –– subtle, deeply touching, and real, being about stuff like aging, how much one can really depend on friends and family after the “fabulous” wedding, one’s greatest fears coming true, and, oh yeah, New York fucking REAL ESTATE.

And it’s about us –– with a date that begins with music at Merkin Hall, with drinks at Julius’ (official touchstone of New York homocinema), and a piercing farewell at the Waverly Restaurant subway stop. I’ve lived it. So have you. Go. Just go.

Contact David Noh at Inthenoh@aol.com, follow him on Twitter @in_the_noh, and check out his blog at http://nohway.wordpress.com/.