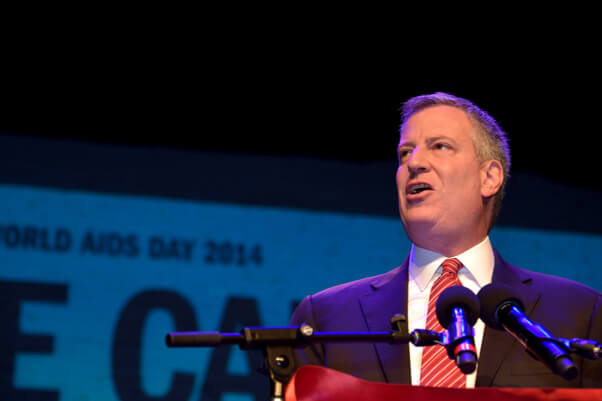

Mayor Bill de Blasio, at a World AIDS Day event in December, endorsed Governor Andrew Cuomo's plan to end AIDS by 2020. | DONNA ACETO

BY DUNCAN OSBORNE | The two city agencies that are most likely to contribute resources to a plan to substantially reduce new HIV infections in New York saw their funding cut in the city’s preliminary budget, suggesting that any effort those agencies might make to advance the plan will be paid for by reprogramming existing cash and not from new money.

The preliminary budget, which was released on February 9, cut the city health department budget from $1.760 billion in the current fiscal year to $1.708 billion in the 2016 fiscal year, which begins on July 1. The Human Resources Administration (HRA) budget was cut from $10.472 billion to $10.334 billion from 2015 to 2016.

The health department funds most of the city’s HIV prevention efforts. The HIV/ AIDS Services Administration (HASA) is the HRA unit that links people with AIDS to benefit programs, such as housing support, Medicaid, food stamps, and transportation assistance.

The plan aims to reduce new HIV infections from the current roughly 3,000 annually to 750 a year by 2020. It was first endorsed by Governor Andrew Cuomo last year and later by Mayor Bill de Blasio. With over 90 percent of the new HIV diagnoses in the state occurring in New York City, the plan will not succeed without the city’s support. More than half of the city’s HIV diagnoses are among gay and bisexual men, so the plan has to significantly reduce new HIV infections in that group.

At the press conference releasing the preliminary budget, de Blasio pointed out several initiatives that were funded with new cash, such as $11.5 million for new bullet-proof vests for police and $18 million to improve emergency response times, but when asked if this budget required HRA and the health department to reprogram existing cash, he emphasized the preliminary nature of the budget.

“Well, first of all, I commend the governor for the goal he’s set, and we’re certainly going to be key participants in that,” de Blasio said. “This is a preliminary budget, so we’ve addressed some of the things that we needed to address immediately, because they were fiscal ‘15 expenditures. We’ve addressed some things that we’re ready to include going forward. A lot more will be looked at and evaluated for the executive budget. So, we certainly want to figure out what role we need to play.”

The mayor releases his proposed executive budget in late April and the City Council holds hearings on the budget both before and after that date.

The state budget, which was released on January 21, contained no new money for the plan either, but did reprogram $5 million in current spending to fund a program to help pay for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which involves HIV-negative people taking anti-HIV drugs to keep them uninfected. It also had a one-time expenditure of $116 million to build 5,000 housing units over five years for the homeless, people with special needs, and people with AIDS. Earlier this year, the city health department launched a program to educate 600 doctors about PrEP and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), anti-HIV drugs used by people with a recent exposure to HIV to keep them uninfected. Last year, Cuomo and de Blasio won a long-sought change in state law that caps rent at 30 percent of income for people with AIDS who receive housing assistance.

“Last year, we were –– we were very, very happy to make progress, finally, on affordable housing for people with HIV and AIDS, but there’s more work to be done,” de Blasio said. “So, we’ll assess that for the April budget.”

Advocates have consistently argued that stable housing is critical to HIV-positive people’s ability to adhere to their treatment regimens and, as a result, reduce their infectiousness to their sexual partners.

The city is facing difficult fiscal times. The de Blasio administration had to close a $1.8 billion gap in the $77.7 billion 2016 budget. State support for the city has declined and with Republicans controlling Congress, federal dollars may also continue to decline.

While the city has seen job growth since 2009, 65 percent of that growth has been in low wage jobs that account for just 28 percent of the earnings over that time, so there has not been much expansion in the city’s tax base.

Expenses have climbed. Mayor Michael Bloomberg closed his budget gaps by not negotiating new contracts with any city unions, so wages and benefits for city employees remained flat. The de Blasio administration has signed contracts with 71 percent of the unions, and the mayor said the city had won $3.4 billion in healthcare savings in those contracts.

In November, de Blasio asked all agency heads to scour their budgets and find savings. The commissioners were told that they could use any dollars saved in their budgets.

“I’ve said to the agencies that I expect them to find cost efficiencies and programs that were not effective enough or might be from another era and bring that back as part of the process leading to the executive budget,” de Blasio said.

The preliminary budget renewed last year’s increase in funding for runaway and homeless youth so that the city could provide 100 emergency beds above the level it had in previous years. During the 2013 mayoral primary campaign, de Blasio and all of his Democratic rivals committed to increasing the stock of available emergency beds by 100 every year until waiting lists at the small number of available youth shelters were eliminated. The new budget does not go beyond the increase implemented last year.

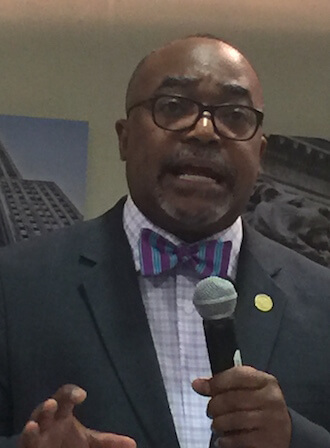

“I asked for additional funds for runaway and homeless youth beds,” said City Councilmember Corey Johnson, an out gay city councilmember who represents Hell’s Kitchen, Chelsea, and the West Village. “One hundred beds isn’t enough. We need to do more.”