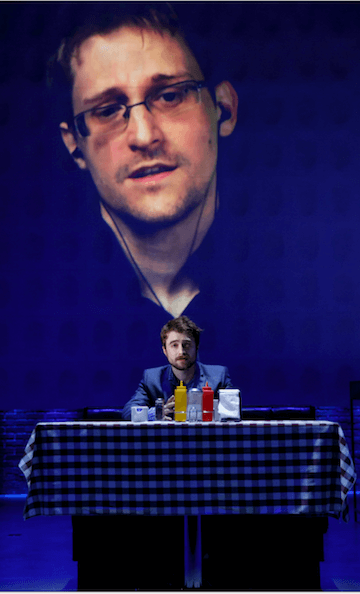

Sue Jean Kim and Ki Hong Lee in Julia Cho’s “Office Hour,” directed by Neel Keller, at the Public Theater through December 3. | CAROL ROSEGG

Julia Cho’s complex and engrossing new play “Office Hour,” now at the Public, is a boldly theatrical examination of a harrowing, contemporary issue: random violence, or more to the point, the fear of random violence and its impact on our culture.

Dennis is a creative writing student at a college where the graphic violence and sexuality of his work have made the faculty leery of him. Not knowing how to handle their anxieties, his professors have simply passed him on to other courses but harbor fears that his fiction may be a way to broadcast intent. And they’re scared of him and what they think he might do. After all he “fits the profile.”

He is now the student of Gina, an adjunct professor, who rather than shying away from him, attempts to get to the bottom of the young man behind the writing, to draw him out from behind his oversized hoodie and dark glasses. This happens in the context of a mandatory office hour when students must meet with their instructor. The storytelling is artistic and abstract. Scenes play out, repeat with different endings — some violent, some touching — leaving the audience unsure of what is real. Of course, that’s the point. What Cho is exploring are the ways in which incidents unfold and the trigger points (literal and figurative) that shape them in one way or another. It’s a brilliant technique, as it keeps the audience in a state of hyper-awareness, never knowing whether a moment will bring healing or havoc — but mindful that either is possible.

Ambition, hopes, and inchoate fears animate three new pieces

Without being heavy-handed, Cho explores how Dennis and Gina might have gotten to this particular point in their lives, touching on themes of racism, alienation, and the breakdowns in communication that bedevil contemporary life. Both Gina and Dennis are sympathetic characters, though they are often antagonistic, and their pain, vulnerability, and confusion are often heartbreaking, providing a fascinating study of character and situation and, most tellingly, underscoring how little we do or can know definitively about what makes people tick.

Ki Hong Lee as Dennis plays the role with a rich physicality that conveys as much as when he speaks. It’s an intense portrayal of a conflicted man struggling with rage and loneliness. Sue Jean Kim is excellent as Gina, driven by a desire to help and finding she might be ill-equipped to handle the situation. The detail and focus that Kim brings to the role are essential for the central conceit of the play to work. We must believe that any of the various scenarios is or could be real, and through her fine work we do. Neel Keller has directed with a keen eye and a flair for tension that will keep you on the edge of your seat… when you’re not almost jumping out of it.

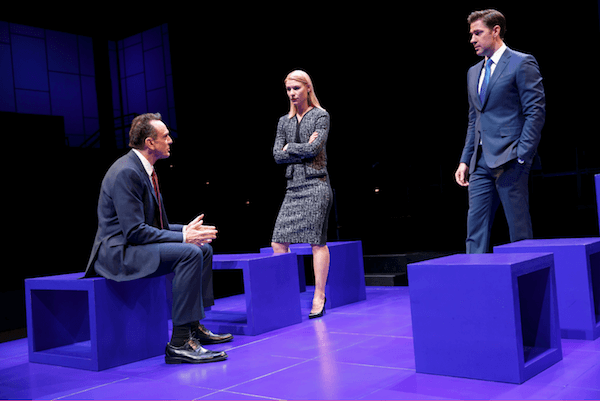

Wilson Bethel and Alex Mickiewicz in Anna Ziegler’s “The Last Match,” directed by Gaye Taylor Upchurch, at the Laura Pels Theatre through December 23. | JOAN MARCUS

“The Last Match” is only nominally about tennis. What Anna Ziegler’s play is really about is the drive to achieve and hold onto success. Tim, an American superstar, is playing Sergei, a Russian challenger at the US Open. Tim at age 34 is considered old, and he is desperate to hang onto his championship for one last match. Sergei is an up-and-comer who has a good chance of defeating Tim and wants to in order to establish himself in the upper echelon of the game. Off the court, Tim’s wife Mallory and Sergei’s fiancée Galina provide love and support but also make demands. Life happens, and the characters do their best to stay on an even keel, though it’s both touching and amusing when things get thrown off balance.

Tim and Sergei banter and compete on and off the court, as the characters move between the two worlds, deftly balanced by director Gaye Taylor Upchurch. The appealing four-member cast is excellent. Wilson Bethel as Tim conveys a great sense of a man at the top who has become aware he may not be able to maintain that peak while straddling the dichotomy between his public and private selves. Alex Mickiewicz as Sergei is often very funny, with his on-court bravado juxtaposed against his fears and his drive to succeed. Zoë Winters as Mallory and Natalia Payne as Galina offer distinctive counterpoints to their respective partners.

The play is straightforward, well-crafted, and highly entertaining. Advantage Roundabout.

Richard Nelson’s gentle yet profound examinations of characters have a quiescent power that often manages to leave one shattered. That was the certainly the case with his most recent trilogy — the Gabriel plays. Following the fates of an upstate New York family through last year’s wrenching election virtually in real time, we watched, transfixed, as their lives happened in front of us. The small moments of this ordinary family’s lives, which could have gone unnoticed, became at once poetic and theatrical — creating remarkably powerful and deeply human pieces of social criticism.

In his new play, “Illyria,” also at the Public, Nelson uses many of the same techniques that made the Gabriel plays so compelling. The play is largely naturalistic conversation, and one has to pay close attention not to miss parts of the dialogue. (Assisted listening devices are available and recommended for even those who might not normally use them.) Events unfold slowly, characters are revealed, and there is no large, dramatic resolution. The topic this time, though, is more documentary, centering on the Public Theater itself during an early year of the New York Shakespeare Festival when city politics and challenging finances almost doomed a young Joseph Papp’s efforts to mount “Twelfth Night.”

In the Gabriel plays, the story was secondary to the characters’ experiences, so their wandering structure made sense. In “Illyria,” however, the linear plot is central to the piece, and Papp is the central character around whom everything centers. (After all, the audience is sitting in the Public Theater and knows how things turned out.) What’s dramatized are not the events but the characters’ reactions to them. In the Gabriel plays that worked because the audience was responding in their own lives to the same cataclysmic events that were affecting the characters — and they brought those feelings to the theater. In an historical play, that immediate, personal context is missing for the audience. Nelson attempts to overcome that by dropping in asides about events outside the world of the play, but it often gives the dialogue a self-conscious feel.

That said, the play is engaging. The characters are real people, including Joe and Peggy Papp, director Stuart Vaughan, actress Colleen Dewhurst, and others. Nelson directs them with the same sensitivity to believable behavior that is his trademark. In the end, however, there are too many events and too much information crammed into the play to work with the directorial and performance style employed here. Despite its laconic pacing, the play seems crowded — overcrowded, really — with incident, as Wilde would have said.

The documentary subject matter is interesting, of course, as part of New York and theatrical history, but ultimately it keeps the audience at a distance and leaves one wishing that the technique better served the topic.

OFFICE HOUR | The Public Theater, 425 Lafayette St. btwn. E. Fourth St. & Astor Pl. | Through Dec. 3: Tue.-Sun at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $75 at publictheater.org 0r 212-967-7555 | One hr., 30 mins., with no intermission

THE LAST MATCH | Laura Pels Theatre, 111 W. 46th St. | Through Dec. 23: Tue.-Sat at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat. at 2 p.m.; Sun. at 3 p.m. | $79 at roundabouttheatre.org or 212-719-1300 | One hr., 30 mins., no intermission

ILLYRIA | The Public Theater, 425 Lafayette St. btwn. E. Fourth St. & Astor Pl. | Through Dec. 10: Tue.-Sun at 7:30 p.m.; Wed., Sat.-Sun. at 1:30 p.m. | $75 at publictheater.org or 212-967-7555 | One hr., 50 minutes, no intermission