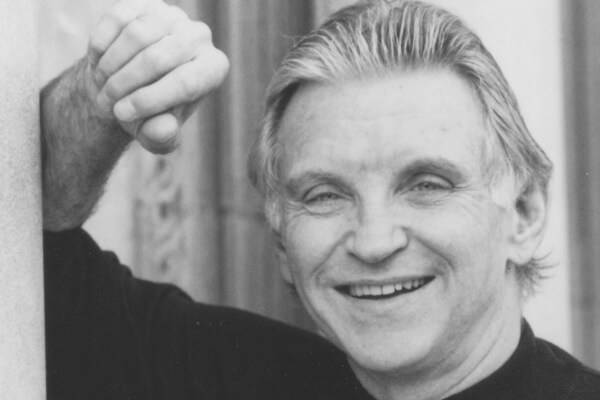

Author and scholar Martin Duberman.

Nothing human is alien to me.” This famous dictum, from the young Marx, Martin Duberman can be said to embody in his life and work. Of course, Marty — as those of us who are privileged to know and love him call him — is always quick to point out that his hero is Emma Goldman, not Marx or Lenin.

A prize-winning historian, essayist, playwright, and novelist, Duberman has been one of the shining lights of queer culture ever since he became the very first American public intellectual of premier class to identify wholeheartedly with the nascent gay liberation movement in the early ‘70s — indeed, he was for a long time the only one so to do. But he did so not just as a writer, with two dozen books to his credit, but as an activist. He helped found what is now the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, the Gay Academic Union, and the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund — and, much later, was the driving spirit behind the launch of Queers for Economic Justice, which has done yeoman work on behalf of the most dispossessed in the LGBT communities, particularly people of color, filling the void for those whose needs are so often ignored by the mainstream institutional gay movement. But as a lifelong, unapologetic radical of the left, Marty has been on the front lines of every important social movement in his lifetime, with both his pen and his person.

He has chronicled political and personal struggles in three volumes of memoirs that have made him an exemplary, self-critical model of Sartrean transparency, and he recognized that the personal is political — before that became one of feminism’s key insights. One of those books, “Cures: A Gay Man’s Odyssey” (1991), has become a landmark queer classic, for it tells of his courageous struggle to overcome internalized guilt inculcated in so many by the homophobia and heterotyranny of US culture as well as the absurd tortures of a bigoted psychiatric profession at a time when same-sex love and desire remained criminalized and pathologized. It is a story of his victory and his emergence as a liberated and militant queer whose example has inspired generations of same-sexers.

He continued to chronicle his extraordinary saga in two more important volumes of reminiscences — 1996’s “Midlife Queer: Autobiography of a Decade, 1971-1981” and 2009’s “Waiting to Land: A (Mostly) Political Memoir, 1985-2008,” in which he recounted how he used his academic prestige to break through the lavender ceiling and get gay studies recognized as a legitimate university discipline. Through his decade-long struggle, against enormous resistance, he established the first such program at any American institution of higher learning — the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at the City University of New York (CUNY), which he served as director for a decade. That’s why he’s justly known as the “Father of Gay Studies.”

Duberman also devoted a considerable chunk of his life to dissecting the racial divide between black and white Americans — from his pioneering studies of the anti-slavery movement, black and white, which changed forever how historians view it; to his hit 1960s play, “In White America,” which used the journals and letters of black folk to tell the story of their endurance and survival through slavery and the ensuing century of bigotry that followed; to his magisterial 1988 biography of the great Paul Robeson, which brought to light many unknown facets of the actor and singer’s life, including his deep involvement in black Africa’s anti-colonial movements.

Acts of bravery have again and again been the hallmarks of Marty Duberman’s life. At the height of the American war in Vietnam, he led the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest Pledge,” refusing to pay federal taxes to finance it. Weary of trying to awaken the consciences of the coddled and privileged children of the haute bourgeoisie, he left a safe chair at Princeton University, abandoning its exquisitely manicured and cosseted precincts, to go teach the children of the working classes at CUNY — where his unique brand of scholarship and activism were sorely needed and where he is now distinguished professor of history emeritus. Few academics had enough idealism to make a comparable sacrifice for the underclasses.

Recognized by his peers — even those who disagreed with his radical politics — as one of America’s preeminent historians, he was given the American Historical Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award for his entire body of remarkable and diverse work.

With all this and more, it’s no exaggeration to say that Marty Duberman’s life has been a heroic one. Although he is now 80, age has neither withered his talent nor dimmed his evergreen radicalism, and his work output puts to shame that of most younger scholars.

In 2007, he gave us a monumental biography of Lincoln Kirstein, a queer who was an important moving force in American arts and culture for half a century. The volume won universal critical acclaim.

Last year, he published “A Saving Remnant: The Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds,” an unusual and scintillating dual biography of two prominent left-wing activists who were also queers and whose paths crossed in many of the same radical causes.

Now, the New Press has just published Marty’s latest book: “Howard Zinn: A Life on the Left,” a masterful biography of the highly influential author of “A People’s History of the United States,” which told America’s story from the bottom up instead of the top down and became a bestseller.

The choice of Zinn, who died in 2010, seems a natural one for Marty, as both men were activists and scholars. As Duberman explains in the introduction, he was drawn to write about Zinn because “we held common convictions on a wide range of public issues. Our views coincided about the justice of the black struggle and the injustice of the war in Vietnam. We shared admiration — our allegiances drifting back and forth — for both anarchism and socialism. We deplored the entrenched and usually unacknowledged class divisions in this country, the growing monopoly of wealth in the hands of a few, and the arrogance and destruction of US foreign policy. We preferred to teach through dialogue not dictation, and we shared a skeptical view of so-called ‘objective’ history.”

Writing a well-rounded bio of Zinn was no easy task, for he had deliberately burned all papers relating to his personal life, leaving only the political residue. But with his typically meticulous research, Marty has ferreted out the facts and given us a complete picture, warts and all.

Zinn, he reveals, dipped his pen in homophobic ink when his activism got him fired from Spelman College, attacking the college's president for tolerating so many “deviants” on the faculty while firing him. Duberman argues Zinn failed to understand either the gay or feminist movements.

Martin Duberman is one of this country’s most admirable and important public intellectuals — and when he speaks, attention must be paid by the discerning among us. That’s why, on the occasion of the publication of his latest book (with two more in preparation), Gay City News thought it important to ask him about some of the burning issues facing America and American queers. Listen up, people!

DOUG IRELAND: As you know, I’m no great fan of Obama, whom I’ve always had pegged as an opportunistic trimmer, but I’m appalled and disturbed by the degree to which the Republicans’ oh-so-thinly veiled racist campaign has struck a chord with the white electorate, especially the working class. As one of America’s leading racial scholars, how do you assess this presidential campaign and the mood of this country in crisis?

MARTIN DUBERMAN: I think there’s so much floating and latent racism in our country, that I believe many wavering centrist white voters were looking for an excuse to vote for Romney. The first debate gave it to them. Obama’s listless performance, in combination with Romney’s seeming moderation, came as a great gift to such voters. Now they can tell themselves with relief that the white guy really is the superior candidate.

That’s the main reason, in my view, why the first debate had such a large effect, turning Romney into the new frontrunner. That’s why so many have ignored the “moderate” new Romney contradicting his own record (and that of his party) on matters like abortion and “pre-existing conditions” for health insurance. That’s why they ignore Romney’s lack of specifics during the debate and his swing back to the right since the debate. The many voters who have suddenly flocked to his standard never liked the “black guy” and are thrilled to have a reason not to vote for him.

DI: What is your critique of today’s institutional gay movement, which in these last years has seemed to have strayed so far from the liberationist politics you have so long espoused?

MD: Elizabeth Birch may no longer be at the helm of the Human Rights Campaign, but her assimilationist policies have triumphed there and elsewhere in the national gay movement. I view this as a disaster, but a predictable one. We left-wingers may have thought otherwise in the early 1970s, but have now learned that our people do not represent a vanguard movement. They want to join the military. They believe in the “sanctity” of marriage and the superior virtue of couplehood. They want to be seen as patriotic Americans, respectable neighbors, and God-fearing believers. On some semi-conscious or unconscious level, they might still know that they are different from mainstream Americans — worthily different — but no longer want to acknowledge it.

I view this as false consciousness. We know somewhere in our gut that we come out of a history of oppression and that that history has molded in us a different set of values and perspectives. The mainstream, rotting in the inequities of our system, stands in desperate need of our special insights. So what do we do? We tell them that our biggest dream is to be just like them, that all we ask is to sign up on the dotted line. We want nothing more — so we tell them — than to settle down into traditional marital relationships and to join the killing machine known as the military. Such a stand on the part of what was once a renegade community is a disgraceful deceit, a denial of our own subversive potential to stand for a more just society, a misrepresentation of our own history and heritage. If we wanted to be true to ourselves and our past, we would challenge sexual monogamy as an ideal, reject gender and racial stereotyping, and deplore the pious formulas handed down by church and state as guidelines for behavior.

And yet… in this short life, it’s understandable that gay people would like to throw off the shame and guilt — and it’s more than residual — they carry as “deviants” and to become accepted as ordinary people. We aren’t ordinary, we aren’t carbon copies of the mainstream. But oh! — how we long to be. Those of us who want to reject the constricted categories of acceptable behavior and rejuvenate our stale institutional state, can expect to be viewed as the enemy — us, not the Angel Moroni and his golden tablets.

DI: If the worst happens, and not only is Romney elected but the Republicans retake the Senate, as seems frighteningly possible, won’t this reveal as bankrupt the access-oriented strategy of the dominant gay organizations and dictate a return to organizing as the primary focus??

MD: Briefly, if Romney wins, those — mostly middle-class whites — who set the agendas for the dominant gay organizations will somehow find a way to make peace with the powers-that-be. They’ve already had a lot of practice. Hopefully I’m wrong, hopefully the gay majority will join forces with Occupy. I wish I saw any evidence of that happening.

DI: How would you assess the direction of academic gay studies these days, which so often strays into arcane theoretical expositions of little or only marginal relevance to the lived lives of queers?

MD: “Relevance” is a strange bird. Forty or so years ago, who would have thought that gay studies had anything of value to contribute to the social sciences and humanities? Yet today its potential relevance to issues as diverse as friendship, love, lust, parenting, relationships is huge — that is, if gay scholars and teachers will emphasize the uniqueness of our perspectives, and if the mainstream world, seemingly deaf in both ears, will learn how to hear.

DI: I’m often disturbed by the historical illiteracy of younger queers about their own political and cultural history. Why is this history — indeed, all history — important, and what are its uses? What are the areas of queer history where much work remains to be done?

MD: Queers and straights alike in this country are ahistorical. Regardless of age, gender, racial and ethnic backgrounds, Americans essentially view the past as boring and irrelevant. Americans obsess about the here-and-now and have only a scant awareness of how past experience has influenced present behavior. Most Americans take the behavioral patterns they currently see around them as universals — as having always existed through time and across culture. They have no awareness of how parochial and time-bound our current values and institutions are. I don’t see this changing any time soon.

DI: What are the most significant gay books of the last couple of years in your view?

MD:

DI: What are you reading just for pleasure these days?

MD:

DI: What are the issues to which today’s gay movement gives short shrift to our peril?

MD: They haven’t changed much. The gay movement still gives short shrift to the amount of racism, classism, and sexism within our own ranks.

DI: I’m by nature and analysis a pessimist, but your writings have always reflected an unshakeable optimism about the human spirit. What gives you hope for our queer futures in these critical days? And do you have a particular message you’d like to address to younger queers?

MD: Oh, my optimism’s shakable, all right! Until Occupy Wall Street came along, I wouldn’t have given a plug nickel for our country’s chances for a progressive future. And then, of course, there’s the nightly news — the segment on Syria alone is enough to hide under the covers.

DI: Do you have a new book or project in mind at the moment?

MD: This spring, The New Press will publish “The Martin Duberman Reader: The Essential Historical, Biographical and Autobiographical Writings.” I’m currently writing a dual biography of Michael Callen and Essex Hemphill, both of whom died just before the protease inhibitors were released. If anyone has anecdotes or archival materials — correspondence, etc. — regarding either man, I’d love to hear about them at martinduberman@aol.com.

DI: Is there anything else you’d like to get off your chest?

MD: Please, everyone, do vote for our flawed, centrist Obama. If Romney wins, our already limited safety net will be cut to ribbons. There’s already far too much suffering out there; let’s not add to it.

HOWARD ZINN: A LIFE ON THE LEFT | By Martin Duberman | The New Press | 400 pages | $26.95