BY DUNCAN OSBORNE | Early in her discussion with Martin Duberman, the author of “Jews Queers Germans,” a “novel/ history, Alisa Solomon, a professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, asked Duberman, “You’ve written in every genre there is… You chose to write it as fiction. Why?”

Why indeed.

Duberman, a distinguished professor of history emeritus at CUNY, has consistently pushed the boundaries of what is history. Some would say that he has stepped over those boundaries and defied the convention — or illusion — that holds that historians must hew to the known historical evidence and never venture beyond it.

In “Jews Queers Germans,” Duberman is telling the story of Germany in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with a focus on just a few real participants in that time — Prince Philipp von Eulenburg, Magnus Hirschfeld, a leading sexologist, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and Count Harry Kessler. Kessler, Hirschfeld, von Eulenberg, and other figures in the book were gay.

“Jews Queers Germans” explores late Imperial Germany in novel not at odds with known evidence

In the course of the roughly 350-page “novel/ history,” Duberman asserts many facts that are known to be true and supported by the historical record. But he also goes beyond those facts to recreate scenes or conversations that may or may not have taken place, but seem to be reasonable given what that record tells us.

“I didn’t choose to write it as fiction,” Duberman said during a March 28 panel with Solomon held at New York Public Library’s main branch at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue. “I didn’t feel it was fiction… If you read this book as history, you will be getting a thoroughly reliable account.”

This is by no means Duberman’s first use of what some historians would say is a controversial method of recounting history. In “Black Mountain: A Exploration in Community,” a 1972 book that explored the 23-year history of Black Mountain College, Duberman came out of the closet and inserted himself into a debate that occurred among participants in the Black Mountain community.

“I was crucified in the historical journals for intruding my personal values,” he said.

Some reviewers asserted that Duberman’s real sin in the 1972 book was to point out that historians have biases and opinions that are present in their work, but masked by the language and structures that are commonly used in histories. His coming out in 1972 also inflamed some critics. Duberman’s technique was merely “a different way of doing history,” as a reviewer of the book and later controversy wrote in 2009.

“For as long as I have been a historian, I have been a discontented historian,” Duberman said.

For most of human history, the great majority of human beings were illiterate. This has meant that the historical record was created by powerful elites who had the ability to record their existence and to shape it in a light that was most favorable to them. What we know very little about, and what Duberman portrays in “Jews Queers Germans,” is the “inner life,” as Duberman said, of historical figures.

“I want to know what is going on inside,” he said. “That is the novelist in me.”

But is this history? Many historians would argue that it is not. Others might disagree. Honest ones would concede that history can be biased.

“Historians all have frameworks, different frameworks, that affect what they talk about,” said Jonathan Ned Katz, a historian who attended the Duberman talk.

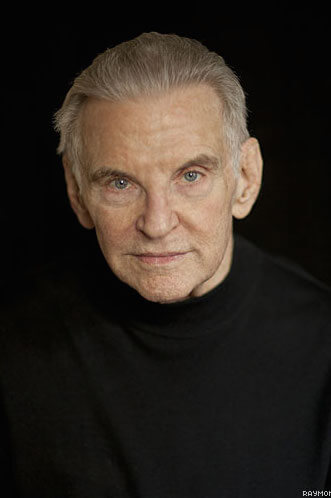

Martin Duberman and Columbia University journalism professor Alisa Solomon at the New York Public Library on March 28. | CHASI ANNEXY

Duberman, who has written more than two dozen books and won numerous awards, expects that “Jews Queers Germans” will receive the same treatment from historians that “Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community” received in the early ‘70s.

“I think that historians will crucify this book as well,” he told Gay City News following the event. And he stands by his approach.

“I would never contradict known historical evidence,” he said. “I believe it stands up as history.”

All of this is not to say that historians should be free to tell histories in any way they wish. Duberman, in addition to never contradicting “known historical evidence,” said that a historian cannot consciously distort “the evidence for a political reason or otherwise,” which has certainly occurred among historians.

In recounting the history of the LGBTQ community, or the role that LGBTQ people played in any history, the predominant sin is one of omission. That omission explains, in part, why some historians, including Duberman and Katz, have been successful. The have been willing to tell a history that other historians will never acknowledge.

“History is wildly loaded from the beginning,” Duberman said.

JEWS QUEERS GERMANS: A Novel | By Martin Duberman | Seven Stories Press | $14.95 | 384 pages