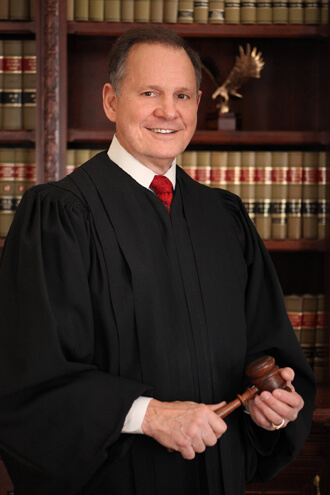

US District Court Judge Robert C. Chambers.

On November 7, one day after the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected marriage equality claims from Ohio, Michigan, Tennessee, and Kentucky, federal district courts in Missouri and West Virginia issued new gay marriage rulings.

Chief US District Judge Robert C. Chambers of the Southern District of West Virginia granted summary judgment to the plaintiffs in a case brought by Lambda Legal and the Tinney Law Firm. Senior US District Judge Ortrie D. Smith of the Western District of Missouri granted summary judgment to the plaintiffs in a case brought by the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri Foundation. Missouri will appeal.

West Virginia was already granting marriage licenses to same-sex couples, in compliance with a ruling from the Fourth Circuit — which has jurisdiction over the state — that the Supreme Court has declined to review. The West Virginia ruling then was part of the mopping up process in that circuit. The Missouri decision staked out important new ground in the Eighth Circuit, where no federal courts have yet ruled in favor of marriage equality.

Eighth Circuit catches up on having pro-equality rulings winding their way up for appeal

Chambers’ ruling in West Virginia was notable, however, for its pointed rebuttal to Sixth Circuit Judge Jeffrey Sutton’s opinion issued the previous day. First, focusing on Sutton’s assertion about the purpose of marriage, Chambers wrote, “Denying marital status and its benefits to a couple that cannot procreate does nothing to further the original interest of regulating procreation and irrationally excludes the couple from the latter purpose of marriage” — which he said even Sutton acknowledged was to “solemnize relationships characterized by love, affection, and commitment.”

And responding to Sutton’s finding that states should be allowed to take a “wait and see” approach on gay marriage, Chambers wrote, “This approach, however, fails to recognize the role of courts in the democratic process. It is the duty of the judiciary to examine government action through the lens of the Constitution’s protection of individual freedom. Courts cannot avoid or deny this duty just because it arises during the contentious public debate that often accompanies the evolution of policy making throughout the states.”

Smith’s Missouri decision is particularly significant because the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, in 2006, rejected a challenge to Nebraska’s constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage. Smith concluded the issues at stake in the suit before him were different from those raised in 2006, making that precedent irrelevant.

The 2006 plaintiffs argued that the anti-gay amendment unconstitutionally deprived them of equal access to the political process by locking a different-sex definition of marriage into the state constitution that trumped any effort to win marriage in the legislature. They did not assert a federal constitutional right to marry, so the Eighth Circuit did not rule on that question, though it did offer the view that the amendment would survive such a challenge.

Smith rejected the Sixth Circuit’s finding the previous day that it was bound by the Supreme Court’s 1972 decision to deny review of a ruling against marriage equality in Minnesota because no “substantial federal question” was at stake. In line with the conclusions of many other federal courts, he concluded that last year’s ruling in the Defense of Marriage Act case made that precedent moot.

On the merits of the case, Smith found that the Missouri marriage ban violates the fundamental right to marry. The court was helped in this case by the defense that Missouri’s attorney general, Chris Koster, made in the case. He did not rely on the typical argument that marriage is all about channeling the procreation of otherwise irresponsible straight couples, but instead simply argued the ban is “rationally related” to the state’s interest “in promoting consistency, uniformity, and predictability.” Smith characterized this as a “circular argument” under which any regulation adopted by the state would be deemed rational, no matter how outlandish. “Merely prescribing a ‘followable’ rule does not demonstrate the rule’s constitutionality,” he wrote.

Given that Smith concluded the ban violates a fundamental right, the lack of any real justification proved fatal. He also found that the ban creates a “classification based on gender,” and any such classification requires heightened scrutiny, a demanding judicial standard the state could not meet.

Smith felt constrained, however, to offer only limited relief, in the form of an order that the Jackson County recorder, Robert T. Kelly, as the named defendant, would be the only state official directed to issue marriage licenses. This seemed peculiar, since the case was originally filed in state court and then the state intervened as a defendant and had it removed to federal court. One would think that with the state as an intervenor defendant, Smith could make his order binding on all Missouri officials.

Even though the state announced it would appeal, Koster, the attorney general, is not seeking a stay on Smith’s decision pending that appeal. (Koster had earlier declined to appeal a state court ruling mandating recognition of out-of-state same-sex marriages but he is appealing one requiring that certain county clerks issue marriage licenses.) While marriage licenses are now being issued, at least in St. Louis and Kansas City, which is located in Jackson County, Missouri may become the state to argue the issue before the Eighth Circuit, unless a Supreme Court order comes down first.

Both judges — Chambers and Smith — were appointed to the federal bench by President Bill Clinton.