Dialectic about strangers, lovers, and others hits home, with a soft thud

“There’s a direct parallel in exploring how you treat your neighbors and how your government treats a foreign country,” said Christopher Shinn, the keenly perceptive 29-year-old author of “Where Do We Live,” in the Vineyard Theatre’s spring newsletter. “The play struggles with the way that our most intimate relationships reveal our basic orientation to the world of others, especially neighbors and strangers.”

Shinn wrote the heartfelt drama in the days just after the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center, which was not far from his home in Lower Manhattan, adapting the tragedy as a foil for his exploration of “responsibility, exploitation, power, and privilege.”

Pretty heady stuff, especially in light of the latest batch of atrocities committed by U.S. armed forces in Iraq. Given its urgently ambitious content and Shinn’s skyrocketing fame—the wunderkind wowed Off Broadway and West End London audiences with “Four,” which he wrote at age 20, as well as several other plays in recent seasons—expectations for his latest work have run high.

Imagine my dismay in what emerges as an intermittently engaging, gently humorous, yet ultimately unsatisfying story that raises far more questions than any play could hope to address. When Shinn says he “struggles” with these issues, he isn’t kidding and the audience struggles right along with him.

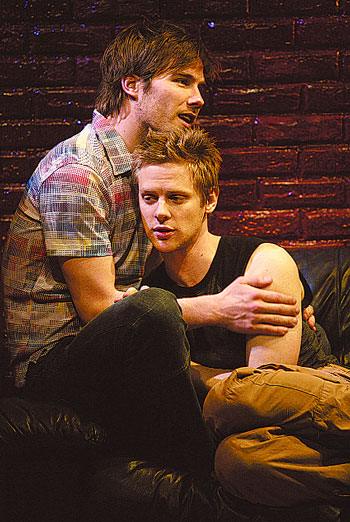

“Where Do We Live” contrasts the worlds of two 20-something outsiders—Stephen (Luke MacFarlane), a white gay writer bent on doing the right thing, and Shedrick (Burl Moseley), a black drug dealer partial to fag-bashing rap tunes—who are neighbors in a Lower East Side building in 2001. Naturally, or perhaps not so naturally, Shinn insists that these worlds mingle, with bafflingly mixed results.

In portraying how people care for one another, there sure is plenty of giving and receiving going on here. Stephen, in a whirl of compassion and guilt, supplies his down-and-out neighbors wronged by a racist culture with pocket money and cigarettes. His boyfriend Tyler (Jacob Pitts), who loves dancing and drugs more than he loves Stephen, defends Billy (Jesse Tyler Ferguson), who defiantly obtains cocaine from the next-door strangers. Stephen’s best friend Patricia (Emily Bergl), a sexy waitress, garners tips—hard cash and investment advice—from cocky Republican Wall Streeters in a bar downtown. Lily (Liz Stauber), who hangs out in Shedrick’s pad, bestows, out of the goodness of her bored heart, a hand job to his disabled uncle Timothy (Daryl Edwards). And in a supremely unnerving scene (caution: plot spoiler here) one of the boys delivers a pounding to an eager male receiver.

Inspired by his illustrious former teacher Tony Kushner, Shinn pumps his play full of political ideology that many playwrights would be too bashful to tackle. Characters debate the failure of America’s welfare system, the fascist quality-of-life tactics—and 9/11 heroics—of then-Mayor Rudy Guiliani, and 16-year-old pig bottoms. They offer advice like “You can’t help everyone. People have to take care of themselves.” True enough, but hardly revelatory to any audience member older than the well intentioned, Village Voice reading idealists depicted onstage.

This intelligent, yet vexing work, confidently directed by the openly gay Shinn, in his debut effort, receives the impressive production treatment one comes to expect from the Vineyard, famous for originating a vastly different and more successful New York-neighbor show, the Tony-nominated “Avenue Q.”

The exuberant nine-member cast dramatizing 15 roles, a good size for a work of this nature, features some bright young talents. Of special note: the adorable MacFarlane (recently seen in “Juvenilia” at Playwrights Horizons) as Stephen, Edwards (“Master Harold… and the Boys”) as Timothy, and Aaron Stanford (star of hit films such as “Tadpole” and “X-Men II”), who plays secondary but vibrant multiple roles.

Rachel Hauck has concocted a convincingly disheveled urban set design with blood-red brick walls and ratty furniture, where the neighboring apartments come across as both separate and melded at the same time.

Despite its shortcomings, “Where Do We Live” is a courageous work of uncommon substance and artistry. Surely, many of the questions raised are worthy of stage time. For example, the play makes us wonder, if we haven’t already, if perhaps Pres. George W. Bush, in his Iraq policy, should adopt the classic New Yorker good neighbor policy—grin politely, avoid eye contact, and mind your own damn business.