Francesco Cilea’s “Adriana Lecouvreur” (1902) has always been an opera that critics love to hate while singers, especially veteran divas, covet the musical and dramatic opportunities offered by the juicy leading roles. Like Puccini’s “Tosca”, Cilea’s opera allows a diva to play a diva.

Here, the opera portrays the semi-historical life and death of an 18th century French tragic actress, Adrienne Lecouvreur, entangled in a doomed love triangle with a royal lover and deadly aristocratic rival. The opera is based on Scribe and Legouvé’s 1849 French boulevard melodrama “Adrienne Lecouvreur” fashioned as a vehicle for famed classical tragedienne Rachel Félix of the Comédie-Française. It offered Félix the opportunity to perform her favorite classical monologues by Corneille and Racine while essaying contemporary romantic melodrama.

The confusing and highly artificial plot typifies the well-made play formula of Scribe — we have intercepted letters, disguises and mistaken identity, dropped bracelets, secret passageways, double deceptions, and Adriana’s nosegay of violets that change hands twice and are returned to her as a poisoned instrument of death. All these contrivances are preserved in the opera’s libretto by Arturo Colautti. However, Cilea’s vibrantly lyrical music keeps our attention on the passionate romantic quadrangle among Adriana, Maurizio the Prince of Saxony, the wicked Principessa di Bouillon, and the faithful stage manager Michonnet. Plot complications fall by the wayside as one good tune follows another.

This New Year’s Eve, the Metropolitan Opera unveiled a new production of “Adriana” for its current reigning superstar diva, Anna Netrebko, surrounding her with the best cast money can buy. The right ingredients were assembled and the evening proved a feast of big beautiful voices, sizzling verismo passion served with sophisticated theatrical presentation, and lots of star charisma. Even the most snobbish musical curmudgeon had to concede this is a damn good show, if not exactly a profound musical masterpiece. There is room for musical entertainments in opera alongside musical genius.

Over the last decade, Netrebko’s voice has gained in spinto resonance and weight in the middle register but has retained a lyrical radiance in the upper register from her youthful days as a lyric and coloratura soprano. Cilea provided an accommodatingly central tessitura for Adriana’s music, making it congenial for an aging soprano with a receding upper register — something Netrebko doesn’t have to worry about yet as her Aida last fall demonstrated. Adriana’s music does require a wide range of colors, subtle nuances, contrast in dynamics, and expressive Italian declamation within that limited vocal range.

Adriana’s entrance aria “Io son l’umile ancella” began unpromisingly — Netrebko’s middle range sounded thick, chesty, and bottled up, and her diction was fuzzy with swallowed consonants. The floated high phrases were disconnected from the core of her voice. Her phrasing sounded disjointed with the varied sections of the aria lacking rhythmic flow. But in the ensuing duets with Michonnet and Maurizio, her voice began to cohere and reveal its many colors.

In Act II’s jealousy duet, Netrebko matched Anita Rachvelishvili’s Principessa de Bouillon in firepower and temperament. Her Phèdre monologue in Act III was searing. I found Netrebko best in duets when she had another singer to work off of. Her phrasing of the Act IV aria “Poveri Fiori” lacked grace and continuity. But I was moved to tears when she joined forces with tenor Piotr Beczala in the duet “No la mia fronte” later in that act. Netrebko and Beczala blended their voices and souls, listening to each other and shaping the music with sensitivity and insight. The two conveyed the need for forgiveness overcoming heartbreak. Gianandrea Noseda and a flawless Metropolitan Orchestra provided sensitive, heartfelt accompaniment from the pit. In that moment, Cilea’s opera sounded like profound music drama.

Netrebko had many small moments of dramatic insight. What Netrebko has, overshadowing any flaws, is glamor and charisma of voice and personality — and in a star turn role like this that makes all the difference.

But she was not the only star turn on that stage. Beczala’s lyric tenor also has gained some dark color in the middle register. His bright upper register rang out freely evoking the impulsive romantic ardor and careless bravado of Maurizio. Beczala cut a romantic figure onstage — a must for a man who has two women fighting over him. As the jealous man-eating Principessa, Rachvelishvili reincarnated the fire-breathing, powerhouse mezzo diva of the golden age of Italian opera. The Georgian mezzo exulted in her vocal power and booming chest tones but was never vulgar or unmusical — acute dramatic and musical intelligence underpinned her every note and movement. I was most moved by the suppressed anguish of Ambrogio Maestri’s aging Michonnet, who realizes that his love for Adriana is impossible but refuses to impose his suffering on her, remaining a loyal friend. Maestri is another powerhouse singer but sang with restraint, emphasizing expression and text. Along with Maurizio Muraro as the Principe di Bouillon and Carlo Bosi as the meddling, unctuous Abbé di Chazeuil, Maestri made the busy dialogue bits sparkle with idiomatic Italian diction.

Noseda conducted Cilea’s music with respect and serious attention to detail. He brought depth to the score’s purple passion movie music sections. A lighter touch was needed in those prancing string-dominated sections where Cilea attempts a pastiche of 18th century baroque style with jejune results.

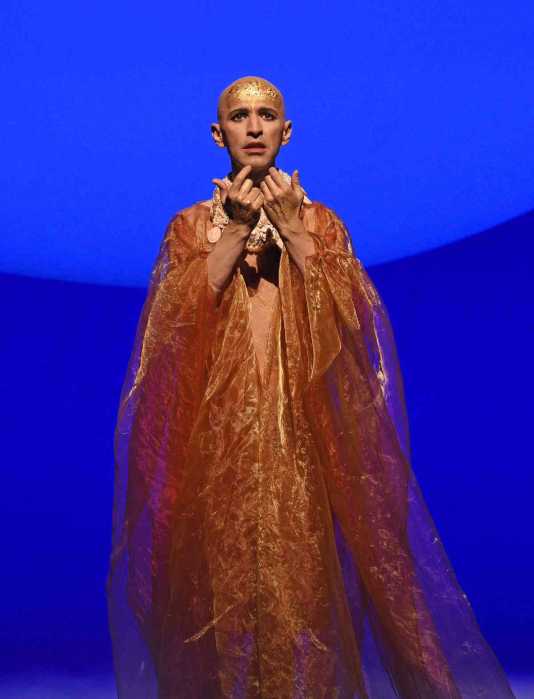

David McVicar’s production originated at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in 2010 and has traveled widely since. McVicar adds a meta-theatrical framework, setting every scene either in a theater or on a set evoking a proscenium stage. The concept is that all these characters are playing roles, if not on the stage of the Comédie Française, then as actors on the stages of court life. The historically accurate sets designed by Charles Edwards are lavish and faithful in period detail as are Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s costumes. I liked the revolving theater set in Act I. But setting Adriana’s Act IV boudoir in front of the same huge theater set made it look like Adriana was reduced to living in the orchestra pit of the Comédie Française. It ruined the intimacy of the final scene.

Otherwise, McVicar’s blocking of the soloists and chorus was deft. Andrew George’s Act III “Judgment of Paris” ballet was a witty baroque homage. The whole evening was characterized by precise yet loving attention to detail and respect for this (much maligned) opera. The stars were aligned properly — and this opera needs stars.