Fiona McCabe, the Irish vice consul general to New York, with playwright Brian Merriman. | VERA HOAR

BY KATHLEEN WARNOCK | As the US Supreme Court prepares to take on the question of marriage equality for the final — perhaps — time, the worldwide push for LGBT rights continues on many other fronts. Marriage equality is also the topic this spring in Ireland, where it will be the subject of a national referendum.

Brian Merriman, an Irish playwright, producer, and egalitarian was in New York to attend the reading of his play “Eirebrushed” at the Irish Arts Center on January 21. The reading was a benefit for TOSOS, New York’s oldest LGBT theater company, and St. Pat’s for All, the inclusive St. Patrick’s Day Parade held in Sunnyside, Queens each year.

The reading drew a sold-out audience ranging from Irish citizens, including a representative from the consulate, to Irish-Americans and LGBT activists and allies. They saw a cast of Irish and American actors portray four of the heroes and heroines of the Irish Rebellion of 1916 and how their exploits were scrubbed from the official histories of the Easter Rising. As the centennial of the Rebellion approaches, Merriman’s play depicts the dreams of these freedom fighters, and how, a century later, so much that they had hoped for has not yet been achieved.

Dublin playwright Brian Merriman recalls the LGBT heroes of 1916, pushes for the new Ireland of 2015

Merriman’s has a long connection to the New York indie theater community as the founder and artistic director of the International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival, which will present its 12th edition this May. Merriman’s festival has brought groups from all over the world to Ireland for more than a decade, putting LGBT theater onstage in a country that only decriminalized homosexuality in 1993.

He sat down with Gay City News on his way to the Queens Pride Winter Gala and talked about how his art and passion for equality are impossible to separate, and how both drive him to keep writing his own plays, presenting international gay theater, and working as an activist for LGBT causes in Ireland and worldwide.

KATHLEEN WARNOCK: First of all, can you give us a brief recap of the marriage equality situation in Ireland as it stands now?

BRIAN MERRIMAN: What your Supreme Court is doing for you, ours has found itself unable to do for us. So there’s a referendum. The courts have maintained that the Irish Constitution defines marriage as between a man and a woman and various court challenges have failed to change their view. So this referendum would gender-neutralize the provision in the constitution, which will then allow for lawful marriage of people regardless of gender. The referendum will take place at the end of April or early May.

But even though the opinion polls are strongly in our favor, it’s easy for people to fear the invisible — and much more difficult when you’re looking at them in the eye. Gay people are out in Ireland; they are on the streets, in the media, and in the workplaces, where they are protected from discrimination. I think that open engagement and confidence in the LGBT people is probably ultimately going to be the bedrock on which this is going to be won. It’s very hard to hate someone you know.

KW: What kind of response is the anti-equality campaign putting up?

BM: We are going to have everything dragged up against us, and that includes obviously, all the religious stuff, which has been funded by evangelical churches from abroad. And as a gay man I’m going to have to sit back, see drag performance artists presented as the norm of gay life by the anti-equality supporters. Drag artists are not the norm, they are special, a glorious part of our entertainment heritage, but if you’re a gay man, it doesn’t mean you have a desire to be female or are not secure in your gender, which is the message of what we’re seeing — gay men are lesser men.

For the next three months, we are going to have awful things said about us. But so be it. We have had so many battles, as I said to one campaigner of my own vintage — we have more left in us. We certainly have the self-esteem and self-confidence to assert ourselves constructively and positively in the face of disrespect and intolerance.

The root of that intolerance is in those who have abused their privilege for the last 100 years and created an unequal society where they were privileged and others were not. Those people have had their power base shaken by the exposure of their own hypocritical standards — the lack of child protection, the lack of respect for women in respect to the churches, and the cavalier manner in which politics wed itself to economic well-being for a few rather than the societal good of all people.

They’re not going to win this one… even if we lose, they are not going to win back that stranglehold of religion that cowed the Irish spirit as a modern nation for so long.

I think Ireland has the capacity to be the first country in the world where the people will endure by their votes: that all of its people and its LGBT people will have their equal rights vindicated. And that’s going to be huge for a country that was among the last to decriminalize it; that has been the clerical dominion and the corruption of the politically conservative. I think it’s a great opportunity for the modern Ireland, which does exist, to define itself in a very public way. And I’m delighted to see the Gender Recognition Bill is also going through the Irish Parliament as is the Children and Family Relationships Bill, which will recognize and secure diverse families. I think we’re all going to get back some power through this referendum.

KW: These kinds of issues go right into what your working life is about — since almost all indie theater folk have to have some kind of day job — don’t they?

BM: My career has taken me mainly into the areas of equality and human rights. I’ve just finished 21 years with the Irish Equality Authority, where I was head of legal services and communications and I ended up an acting CEO. Recently, we were merged with Irish Human Rights & Equality Commission.

KW: And that career has informed what you do as an artist, hasn’t it?

BM: I actually took both a career break for six years to work in professional theater, and then a job share, so I could continue in the theater. It was a good time for me theatrically. I was involved in about 360 productions, and had also decided I really wanted to concentrate the brain in another place. So I took my master’s degree in equality studies at University College Dublin.

When I finished the academic studies, I suppose I put what I learned about Oscar Wilde — having played him — and the theater and what I was practicing in the area of equality and human rights into a career in a country that had only decriminalized being gay for 10 years. And I felt that the visibility and identify of gay people had not been established thoroughly after 125 years of criminalization. All that went into the melting pot and out came the Dublin Gay Theatre Festival.

KW: As someone who also juggles my professional and theatrical careers, I know that’s hard to do. How do you balance them?

BM: Terribly badly I would say! I always earned an income from theater, and since the festival that’s gone because the festival takes so much time. It is the second decade now and it’s a little bit frustrating that despite our huge success, we still haven’t attracted adequate resources.

KW: From the community or the government?

BM: From both. The festival does require an enormous volunteer force to maintain its standard. I work on it maybe six hours a night, most lunchtimes, six or seven days a week. It’s now, of course, an all-year process. No sooner does the festival finish than we’ve got to do all the administration, tidying up, then I head to Edinburgh [for the Fringe.] I read about 2,000 synopses before I get to their festival. I probably see eight plays a day, five days a week. It’s grueling, but from there at least I establish and reconnect with the Irish and international LGBT theater presence.

KW: Now that you’ve had a decade of productions, can tell us what kind of impact the festival has made in Ireland?

BM: In making Dublin the international center for gay theater, which I think it is, at this stage, what is essential for us to achieve and keep doing is that the homegrown artistic expression matches what comes in, and we do that. It took a lot of confidence building, awareness raising, and talent identification. What I did was: those that came my way, if I thought they had a story in them, I encouraged them to write, and offer some mentorship, and of course, if it reached a standard, I had created a facility where it could go on the stage.

And I wanted the Irish presence to be valid and to balance with the opportunities we were establishing to invite other voices to come to Ireland. Particularly voices that couldn’t find a stage in their country due to underfunding the arts, the laws, and lack of valuing the contribution of gay citizens or the cultural policies of George W Bush.

KW: And where has everyone come from over the years?

BM: The five continents have all been represented. Obviously, because gay theater is hard to sell, I’ve got to maximize its appeal to an English-speaking audience. In that way, it does rule out certain countries, but they’ve come to us from Ukraine, Israel, Poland, Venezuela, Zimbabwe, the US, Canada, South Africa and Australia, Poland, Italy, and England of course.

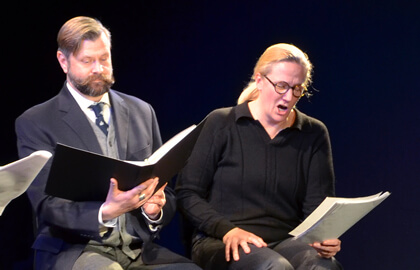

Chris Weikel, portraying Sir Roger Casement, and Honor Molloy, playing nurse Elizabeth O'Farrell in the January 21 reading of Brian Merriman's “Eirebrushed.” | VERA HOAR

KW: You could write a book. In fact, you have written a book!

BM: A lot of the great memories of the festival are sketched out in my book “Wilde Stages In Dublin,” and the title is not just referring to Oscar, for his was the only language we had to discuss LGBT stages of development in the liberation of gay people in Ireland, acceptance of the artistic and cultural contribution we’ve made. I think you might be surprised that the book is not so much about the major plays; it’s also about the personal. It’s about a man in his late 60s who approached me one night and said to me, “I’m gay. You’re the first person I’ve ever told.” When you create a safe space in a theater and give them a story that people can relate to, it can relieve them of the constructed oppression.

One year, some award-winning actors flew in just to go to the plays — Juliet Mills and Maxwell Caulfield, whose daughter was in a production of “Corpus Christi.” Nobody tells me these things until after! But then, I’ll come across a young stagehand and engage with her and realize that they have a great story, they were drawn to the festival because of it. And a year or two later their play is onstage, and that’s important.

And, it’s lovely to see families come. We had our first school group in 2014 for the play “Aunty Ben,” which was a children’s play with a trans character. We’ve had children in before for productions of Wilde’s “The Happy Prince.”

We’ve also had support from interesting places like the Israeli Embassy and other embassies and consulates. Of course, we sometimes had to give them a push to acknowledge the contributions of their visiting artists.

I’m proud of the political engagement of the festival. It’s been spoken about in the Irish Parliament and Senate, positively. The lord mayors of Dublin have shown terrific eagerness to validate what we do. It’s important for us to be visible in places like that to assert our right, as every other citizen has, to be endorsed by the first citizen of the city.

KW: How does what you do with the festival and your activism compare with what you’ve seen in New York during your stay here?

BM: As a visitor, I have to say you have a terrific network. My generation is powerful as networkers and influences here, and we’re not any longer in Dublin. The club and community scene is very ageist and rather than standing on the shoulders of the ones who came before, the older people are dismissed. It doesn’t seem to be that way here.

KW: There are some who would disagree with you…

BM: I’m sure! My generation is visible but there are very few of us left. Many of them found a partner and went to live in towns and villages through Ireland. The few of us that are left are certainly manning volunteer efforts with fewer numbers.

I think we have a very accessible and visible gay center in Dublin. It’s diverse and creates a lot of potential for things to get done. We’ve got 184 different nationalities in Ireland now. Polish is the most spoken language after English. And the Brazilians are beautiful, and everyone wants a Brazilian boyfriend! We have a visa deal with some other countries, where it’s easier for them to come to Ireland, and many countries have certainly made a huge impact. Now the Filipinos are having a great impact in the health care professions.

KW: In that respect, with the melting pot climate, it seems to be very much like New York City.

BM: Well, I know it’s been wonderful to meet all these new people. I’ve heard a lot about Brendan Fay [the co-founder of St. Pat’s for All] over the years. And I really salute those who have been down the long, hard road maintaining their energy. They are continuing to work to make it better. And it’s a very positive thing for them to do to ensure the modern, diverse, inclusive Ireland is celebrated and not some romanticized notion of a miserable past.

KW: I’m a big fan of St. Pat’s for All. It seems to me a positive response to resistance from groups this late in the 21st century who would deny the equality based on someone being LGBT.

BM: There’s a lovely view of Ireland that is very heartwarming, and I hope people will come to visit the festival in May. But those who are part of the diaspora must not impose their green-tinged memories on the progress that Ireland has made as a modern European country. We have struggled to liberate ourselves. And we didn’t do that for others to try and drag us back into some kind of land of leprechauns where all the comely maidens did their duty by the drunken Irish man, and it’s not for the likes of the Ancient Order of Hibernians to dare to define us in such a fake way. It only demonstrates how far removed they are from the heritage and legacy of their ancestors. When the Irish came to America we not only built it, but we also engaged hugely in the political movements, in the Democratic Party, in the areas of social justice, and that was what the Irish did here then to pursue equality and social justice, because they were not free to do it at home.

Now we find some of their privileged, comfortable, smug descendants trying to wrap us in a rather glowing green flag, which has papal watermarks. And that’s not Ireland. And I invite them to do what everybody should do when you want to know somebody’s accurate identity: you don’t tell them, you ask them. And when they tell you, you listen and you respect, and the St. Patrick’s Day Parade without the creativity and citizenship of the LGBT community is a fake. And I say that knowing that it was the LGBT group that won the prize one year at the Dublin parade.

The St. Pat’s for All Parade steps off at 2 p.m. on March 1 from the corner of 43rd Street and Skillman Avenue in Sunnyside, Queens. More information at stpatsforall.com.