Minnelli takes the stage at Carnegie Hall for a Kander and Ebb tribute

It was, I thought—my stomach turning over—like watching a train wreck.

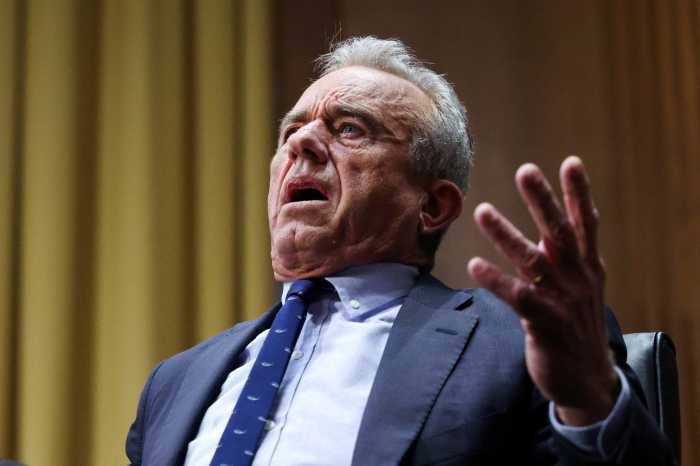

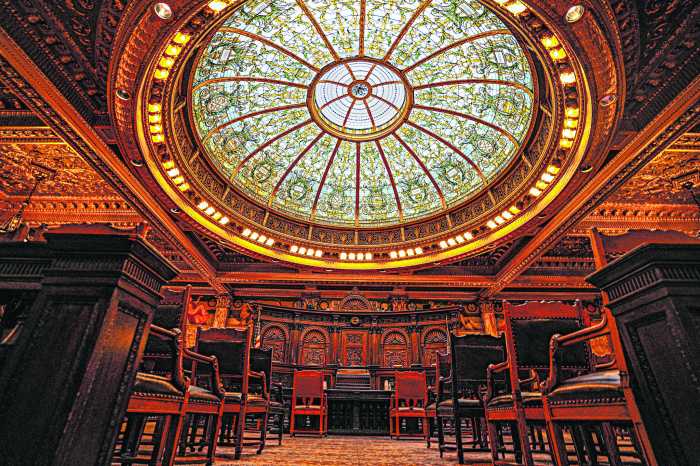

Next to me, my wife was crying, shivering, shielding her eyes. This was Monday night in Carnegie Hall, and Liza Minnelli had taken to the stage in a grotesque simulation of Liza Minnelli singing the title song from “Cabaret.”

The event was the Lauri Strauss Leukemia Foundation’s salute to those premier songwriters of our lifetimes, John Kander and Fred Ebb. In the first half of the evening, everyone had done very well, in particular Lainie Kazan, who’d started things off brilliantly with her powerhouse of broken-love medleys. The performers were all good—each of these celebratory talents, a dozen or more headliners, from Maureen McGovern and Ty Stephens all the way down to Freddy Roman, who substituted laughter (ours) for song, and Skitch Henderson, who amiably mushed his way through the proceedings as conductor of the New York Pops.

And now it was the end of the evening, and the prize, that the whole now-shrieking house had waited for as a sort of glorious dessert capping a three-hour meal, had emerged from the wings to pay her own tribute to the two men—two great artists—who had indeed been her two best friends ever since they had all three conjoined for “Flora, The Red Menace,” in 1965.

She was here to once again sing their songs, but as the several thousand onlooking listeners saw and heard in an instant, she could not, properly speaking, sing. To all appearances, she could but barely move—thanks to two hip replacements—she was successful only at calculated angles. Her mother always had a well-advertised weight problem, and so has Liza, but this was beyond advertisement: it was right there, like a large square abandoned house.

The costuming—somebody should go to jail for this—emphasized the boxlike grotesquerie. It was like watching a character out of “The Simpsons” pushed willy-nilly out on stage. And the singing—well, she broke off to make a rather winning joke at her own expense.

“I have this communication,” she said. “I rewrote it in large letters so I can read it to you. It’s from my two best friends. It says they’ll bail me out of jail if I promise not to beat them up.”

But she still had to sing, or try to sing, and we had to listen, and soon wished we were elsewhere. And I thought of Judy at the Palace, on her last and final comeback, 1967, and how badly she had been costumed, though not as badly as this, and how Garland’s voice by then was really gone, or so everyone said and thought, and how we wondered would she try for the high note, or would she crack long before she made it. And then, there in the large looming Palace, where she’d had her big Broadway triumph 15 years earlier, she dragged her kids up on stage. Then a while later she got to where she had to, wanted to, tackle the song “Chicago” (Mack Gordon and Harry Revel, not Kander and Ebb), one of her much-loved standbys, which has that high note right in the middle, “Chi-caaaaaa!-go”—and by Jesus she hit it, Judy did, pure and straight and strong and thrilling, and then of course she’d sat down, curled up, at the footlights, and lulled us all home with “Over the Rainbow.”

Less than two years later, Judy Garland was dead in some sordid room in London’s Chelsea… “I always thought she’d outlive all of us,” Liza said.

And now, here in Carnegie Hall, Liza Minnelli, two bad hips and all, was being helped to get herself seated at the apron of the stage, and from there she’s embraced Fred Ebb and John Kander, getting them to arise from their front row, center seats and join with her, lovingly, in singing what has become this city’s, and in many ways this nation’s, signature song.

“Start spreading the news!” They sang—the three of them hugging each other—“New York, New York,” and we rocked, we clapped, we were born again, a thousand or more of us in Carnegie Hall. Like mother like daughter, déjà vu all over again. It’s never over till it’s over.