Who will there be to be angry at Larry Kramer’s memorial service (if and when we are able to have memorial services again)?

When his gay and AIDS activist comrade Vito Russo died of AIDS in 1990, Kramer got up in front of a packed service at the Great Hall of the Cooper Union — then home to ACT UP meetings that attracted 500 people every Monday night — and spat, “You killed Vito! Every one of you!,” chiding us all for not doing enough amidst the plague that defined our gay lives and his own activism and art.

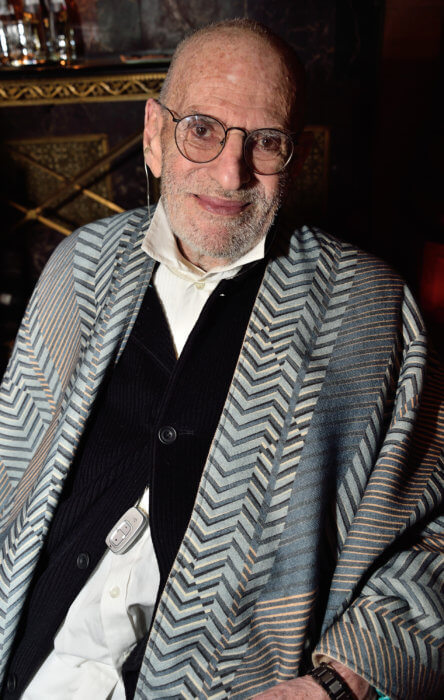

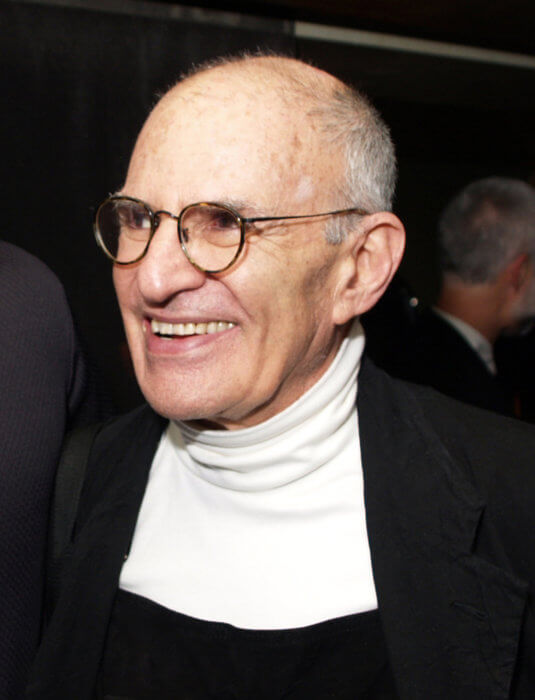

Kramer’s work arguably saved millions of lives around the globe. His own life ended May 27, 2020 after a long illness and a bout with pneumonia. He was 84 and is survived by his husband, David Webster, and those countless millions.

A screenwriter, playwright, author, his passion infused his impatient challenges to the nation and the LGBTQ community

Kramer will be most remembered as a catalyst. When mysterious maladies were killing off young gay men in 1981, he crowded scores of us into his 2 Fifth Avenue apartment on Washington Square to listen in terror to Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien’s description of what was happening — the beginnings of an epidemic that would turn into a pandemic and what Kramer always called “a plague.”

Kramer then gathered some friends in his kitchen to found the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in a community not practiced in philanthropy for itself. He took a tin can out to Fire Island to collect money for the new group, stood on the pier himself, and took in a grand total of $60. He demanded government and press attention but could get neither from New York’s closeted homosexual Mayor Ed Koch nor the city’s then anti-gay leading newspaper, The New York Times. And when GMHC did get a meeting with Koch, the group excluded its angriest board member: Kramer.

Much of this is dramatized in Kramer’s own “The Normal Heart” from 1985 at the Public Theater, a searing and topical play that nevertheless spoke to a new generation in 2011 and won Best Revival of a Play for him. In 2014, the American Theatre Wing awarded Kramer a special Tony for his humanitarian work.

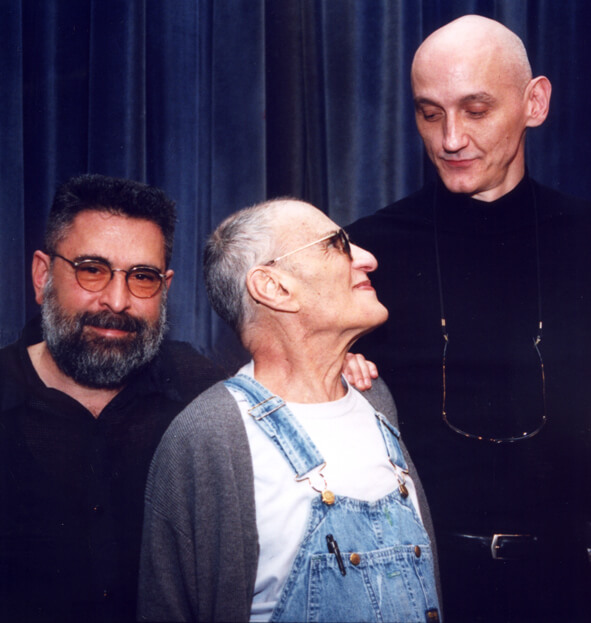

His friend Dr. Larry Mass, who wrote the first articles about the emerging epidemic in May 1981 in the New York Native (“Cancer in the Gay Community”) and was also one of the founders of GMHC, once said of him, “Larry Kramer is a colossus of courage, genius, character, drive, achievement, and providence with no counterpart. He has cut a huge swath across populations, communities, continents, time spans, literature, theater, medicine, and science. Where would we be without him? Alas, the answer to that is already nipping at our heels.”

When Kramer wrote his controversial and picaresque novel “Faggots” in 1978, he was relatively unknown in gay activist circles. It sparked a furor in the community for unapologetically portraying promiscuity among gay men. (The gay Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop on Christopher Street refused to stock it, but it sold well elsewhere.) He also wrote an op-ed piece in The Times saying gays in New York didn’t deserve our rights because we didn’t work for them like our brothers and sisters in San Francisco — ignoring the profound political differences between that small city in California and the metropolis in New York that at that time consisted of four conservative boroughs in addition to Manhattan.

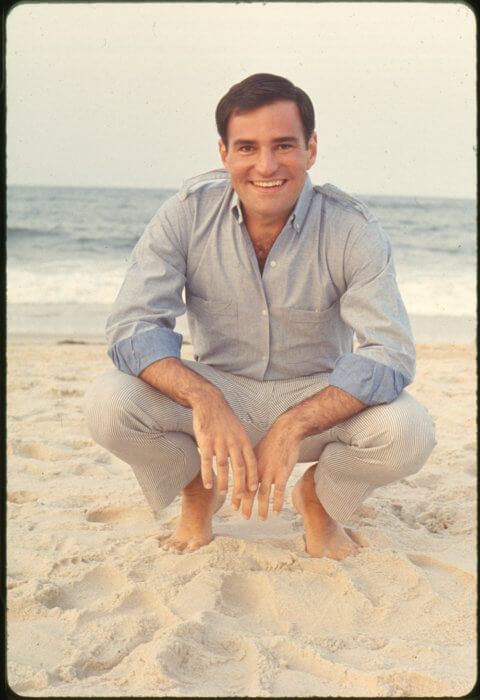

But prior to that, Kramer was an Academy Award-nominated screenwriter for the 1969 Ken Russell adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s “Women in Love” starring Alan Bates and Oliver Reed, playing friends who engaged in a famous nude wrestling scene, and Glenda Jackson, who won the Oscar for Best Actress.

Kramer went on to become a movie producer and while his production of a star-studded musical of “Lost Horizon” in 1973 was a critical and box office failure, it paid him enough money, which — invested by his brother Arthur Kramer — gave him the financial security to pursue more daring projects such as writing “Faggots” in 1978 and, when AIDS hit in 1981, taking a lead in pushing the gay community to heightened activism.

Through sheer force of will, he was able to get activists to join him at that first meeting in August 1981 that led to the founding of GMHC. Kramer was the group’s firebrand, writing front-page articles in the gay New York Native — such as “1,112 and Counting” in 1983 desperately trying to draw attention to the thousands who were sick and dying, usually within a year or two at most of diagnosis, and urging gay men basically to curb our sexual practices until we knew exactly what was causing the syndrome and how to protect ourselves from it.

“All it seems to take is the one wrong fuck. That’s not promiscuity — that’s bad luck,” he wrote.

That led some in the community to condemn him as anti-sex, but attacks never deterred him.

“If this article doesn’t scare the shit out of you,” he wrote, “we’re in real trouble. If this article doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage, and action, gay men may have no future on this earth. Our continued existence depends on just how angry you can get… Why isn’t every gay man in this city so scared shitless that he is screaming for action? Does every gay man in New York want to die?”

As so many die due to government inaction and ineptitude and malice in the current pandemic, Kramer’s 1983 piece bears re-reading.

Kramer called for “a pool of 3,000 activists prepared to engage in civil disobedience,” but that did not materialize until his co-founding of ACT UP four years later.

He once threw a drink in the face of closeted conservative activist Terry Dolan when he encountered him at a Washington party.

Kramer also yelled at The New York Times, whose executive editor Abe Rosenthal, killed coverage of AIDS in its early years, and television producers. Joe Lovett, an out producer who did the first big national piece on AIDS on “20/20” at ABC in 1983, said that Kramer’s yelling at him gave him the courage to keep going back to the executives at ABC to push for the kind of coverage it needed and deserved.

Kramer got Joe Papp to produce his searing play “The Normal Heart” in 1985, during the darkest times of the AIDS plague. It was the highest use of theater — telling an urgent story to people living through it. At a preview, I saw several of the people portrayed in the play — Rodger McFarlane, Larry Mass, and Kramer himself — sitting in the audience for the alley staging. Kramer famously went up to Times critic Frank Rich at a preview he was reviewing and said, “I have never wanted someone to like something so much.” The play starred Brad Davis who soon had to be replaced for health reasons by Joel Grey. (Davis eventually died of AIDS complications himself.)

As GMHC became much more focused on services instead of advocacy, Kramer used a March 1987 “Second Tuesday” speech at the LGBT Community Center to demand more militant action of us. Indeed, it was a command performance — Kramer calling everyone he knew and demanding we show up to hear what he had to say. (“Just fucking be there,” he told me and hung up. So I went along with 300 others.) That led to the founding of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP — gathering scores and then hundreds of activists together for weekly meetings (and countless subcommittee meetings) to fight for government action after years of neglect by Koch, New York Governor Mario Cuomo, and, most notably, President Ronald Reagan who at that point — six years into the plague — had yet to publicly address the crisis.

When Reagan did finally speak on AIDS at an AmfAR event in June 1987, Kramer was there in the tent — grateful that we might finally see a step-up in federal commitment. But when Reagan, flanked by Dr. Mathilde Krim of AmfAR and AIDS activist Elizabeth Taylor, drifted into some right-wing rhetoric about forced testing, Kramer joined in the chorus of boos from many in the audience.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with whom he often tangled (Kramer once comparing him to Adolf Eichmann), famously said, “In American medicine there are two eras. Before Larry and after Larry.”

ACT UP led the fight to speed up government approval of drugs to treat HIV. But it wasn’t until 1995-6 that an effective combination of drugs began to allow people with HIV — including Kramer himself — to survive to relatively normal lifespans.

Bill Dobbs, longtime activist and member of ACT UP in the early years, said, “Larry was a critical catalyst in the fight against AIDS. He was a scold, an artist, not much of an organizer, but a powerful force in pushing back against a deadly pandemic.”

Kramer was particularly furious with Koch, the closeted mayor. When Koch spoke at a GMHC AIDS Walk, Kramer alone stood at the front of the opening ceremony outside Lincoln Center with a sign saying, “Ed Koch: The Worst!” The GMHC organizers did not dare have the police remove him. When Koch once told an interviewer he “happened to be a heterosexual,” Kramer and others carried signs at an ACT UP demonstration at City Hall reading, “Koch: ‘I’m heterosexual.’ And I’m Marilyn Monroe!”

Kramer moved into Two Fifth Avenue in the early 1970s, renting there when such places were affordable. When Koch moved into the building after his mayoralty ended in 1989, Kramer would insult Koch when he saw him. When the building’s board ordered Kramer to stop speaking to Koch, the next time Kramer saw the former mayor he said to his dog, “Molly, that’s the man who killed daddy’s friends.”

Kramer also took on anti-gay religious leaders, especially New York Cardinal John O’Connor, who led the opposition to the city gay rights bill in 1986 and who was infamously appointed by Reagan to his AIDS Commission in 1987. In the book “Gay Pride” by Fred W. McDarrah and Timothy S. McDarragh, Kramer wrote, “The new Catholic archbishop, John O’Connor, upheld his group’s tradition of bigoted opposition, but he was more than counterbalanced by the common decency of religious leaders such as Episcopal Bishop Paul Moore, Rabbi Balfour Brickner, and, in his own church, Sister Jeannine Gramick, Reverend Bernard Lynch, and the members of Dignity.”

Kramer was a staunch supporter of ACT UP’s 1989 “Stop the Church” action inside St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

“It made everyone afraid of us,” he said. “They did not know what we might do next.”

Kramer followed “Normal Heart” with “Just Say No” (1988), a short-lived polemic against the Reagan family, and the Off-Broadway critical hit, “The Destiny of Me” in 1992, charting Kramer’s early life and struggle with AIDS and as an AIDS activist. His books also included “Reports from the Holocaust: The Making of An AIDS Activist” (1989), a collection of his essays and polemics.

Richard Lynn wrote, “He asked me medical and science questions when he was writing ‘The Destiny of Me’ and wanted to get everything to be precisely correct. His devotion to telling the truth, no matter how uncomfortable it was to hear, is unmatched.”

After the 2004 reelection of the anti-gay George W. Bush, Kramer gave a speech (later a book) titled, “The Tragedy of Today’s Gays,” saying, “Almost 60 million people whom we live and work with every day think we are immoral. ‘Moral values’ was top of many lists of why people supported George Bush. Not Iraq. Not the economy. Not terrorism. ‘Moral values.’ In case you need a translation that means us. It is hard to stand up to so much hate.”

Veteran gay activist Ron Madson last saw Kramer outside the revival of “Normal Heart” on Broadway where producers nixed a program insert on AIDS.

“He stood at the lobby handing out leaflets that scolded people that the epidemic has not ended,” Madson recalled. “I truly mourn his loss. He showed us how to be advocates in the face of hateful obstruction. He was a raptor when society wouldn’t even tolerate a gay gadfly. His soul lives in every one of us that he helped save. His passing is a colossal loss. I’m in tears.”

Between 2015 and 2020, Kramer published Volumes I and II of his sprawling, nearly 1,700-page “The American People,” a reimagining of US history, guided by “Fred Lemish,” his protagonist and alter-ego in “Faggots.” In his tomes, he proclaimed the homosexuality of everyone from George Washington and Abraham Lincoln to Mark Twain. When he tried to get the producers of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “Hamilton” to deal with Alexander Hamilton’s bisexuality and love for John Laurens, he was rebuffed and Laurens was portrayed as a devoted friend instead.

Laurence David Kramer was born June 25, 1935 in Bridgeport, Connecticut, but was raised in Washington, DC, from 1941 by George and Rea Kramer (nee Wishengrad). While he hated his father, his mother was an inspiration to him and he felt protected by his older brother Arthur. While he followed Arthur to Yale in 1953, Kramer — like most all but a handful of homosexually-oriented people of his generation — struggled with his sexuality, saw a psychiatrist about it 20 years before it was removed from the index of mental disorders, and tried to take his own life. But Kramer did manage to connect romantically with a gay German teacher at Yale and graduated in 1957. (He had a very complex relationship with Yale, which he desperately wanted to teach gay studies. He donated his papers to Yale and his brother Arthur donated a million dollars to the school in 2001 for a Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies after an acrimonious four-year fight about how the money would be spent. It was shut down in 2006. The university nevertheless gave him an honorary degree in 2015.)

After a brief stint in the US Army, Kramer moved to New York in 1958, eventually working for Columbia Pictures helping produce — out of London — such films as Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove” and David Lean’s epic “Lawrence of Arabia.” He optioned the rights to “Women in Love” and its success became his calling card.

Kramer learned he was HIV-positive in 1988 — seven years after having thrown himself into AIDS activism. A long-long-term survivor, he eventually needed a liver transplant and was the first person with HIV to get one in December 2001 when expectations had risen further that people with HIV could live normal life spans. The NIH’s Fauci, often his antagonist but eventually his friend, played a role in seeing to it that Kramer got the operation.

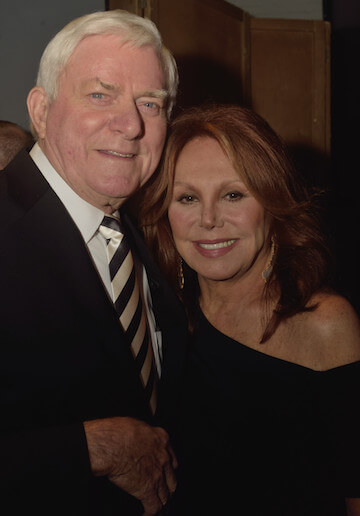

Kramer is survived by his husband, architect/ designer David Webster who he had an on-again, off-again relationship with in the mid-1970s (related fictionally in “Faggots”), but with whom he reconnected in the 1990s, bringing great calmness to Kramer’s personal life. When Kramer fell deathly ill in 2013, the men were married in Kramer’s ICU hospital room by Judge Eve Preminger surrounded by a few close friends — one of many scenes in Jean Carlomusto’s fine documentary, “Larry Kramer: In Love & Anger” (HBO, 2015).

Ann Northrop, an ACT UP stalwart and co-host of GAY USA, said, “I loved Larry. We didn’t always agree. But I appreciated his love of gay people and his imperative that we hold ourselves to a high standard.”

AIDS activist Peter Staley, who joined ACT UP weeks after it launched in 1987, paid a complex tribute to Kramer on Facebook, talking about how happy Kramer was “finally witnessing the community he dreamed of.”

He wrote, “Larry told us to fight back. In short order, we guilt-tripped an entire nation of people and two Republican presidents to react. By 1990, the AIDS research budget at the NIH hit one billion dollars a year.”

While praising the activist Kramer, Staley also said, “The second Larry was the moralist whose finger-wagging, like all finger-wagging, brought adulation from other moralists, but had no effect on the rest of us” but added to the shame that some gay people feel.

Author David Strah, who as a student at NYU in 1986 took care of Kramer’s dog Molly and became his friend, said, “He inspired me to be an empowered proud gay man like no one else. He invited me to the first ACT UP meeting. But his example of fighting for our lives also pushed me to make key decisions like having children and now, as a therapist with LGBT people, to instill a sense of pride in my clients.”

ACT UP veteran Mark Milano wrote, “Larry is the reason I’m an activist. He helped me change from a timid, disinterested bystander to someone who has found the courage to confront two presidents, one vice president, and countless bureaucrats and drug company profiteers to their faces.”

Gay activist Louis Flores, whose latest cause is saving NYCHA, wrote, “The only way to challenge power is to be outspoken. You have to speak out of turn. Larry did that, and he set an example for us, for me, in particular. Social movements cannot compromise until you win.”

Gay playwright Bill Crouch wrote, “He saved me a thousand times over, as well as many, many of my friends and peers. How? By screaming ‘Plague!’ over and over to anyone within earshot. He was a genius and he saved us.”

Gay and AIDS activist John Voelker wrote, “For the 1989 Pride Parade, he was on his balcony at 2 Fifth with Vito Russo, who was then ill, and a huge ACT UP contingent marched past and did a die-in or big cheer or something for Vito. Larry turned to him and said fondly, ‘These are our children.’ We are all orphaned now.”

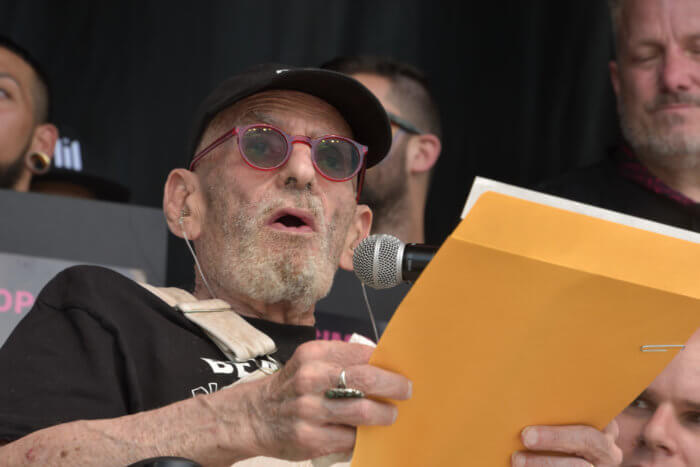

Late in life, Kramer kept returning to his theme that we as a community had failed. With 35 million dead of AIDS and 35 million more infected with HIV, it was hard for him to focus on the major advances in treatment through activism that he was such a critical part of and that kept him and countless millions alive. Failure was the theme of his last major public address at the Central Park rally after the Queer Liberation March on Pride Day 2019 that can be viewed here: youtu.be/3GZV3aU8WV0.

“I love being gay, I love my people,” he said that day. “I think in many ways we’re better than other people. Most gay people I see appear to have too much time on their hands. If you have time to get hooked on drugs and do your endless rounds of sex-seeking cyber-surfing until dawn, you do have too much time on your hands… If we do not fight back against our enemies, we will continue to be murdered. But we have a population that is inept at organizing ourselves… We are not very good at fighting back.”

As fierce as Kramer could be in public, he was a warm, gentle man with his friends and loved ones. He would sometimes wonder why people were afraid of him. He did not suffer fools gladly. When he would speak to audiences of college students and they would ask his advice on what to do, he would often say, “You figure it out.” As he himself did.

“Larry’s timing couldn’t be worse,” Staley wrote. “The community he loved can’t come together — as only we can — in a jam-packed room, to remember him. We can’t cry as one and hear our community’s most soaring words, with arms draped on shoulders in loving support. Broadway has no lights to dim, which it surely would have. Can we please do this next year?”

At his death, Kramer was at work on a new play in response to the current pandemic, “An Army of Lovers Must Not Die.”

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.