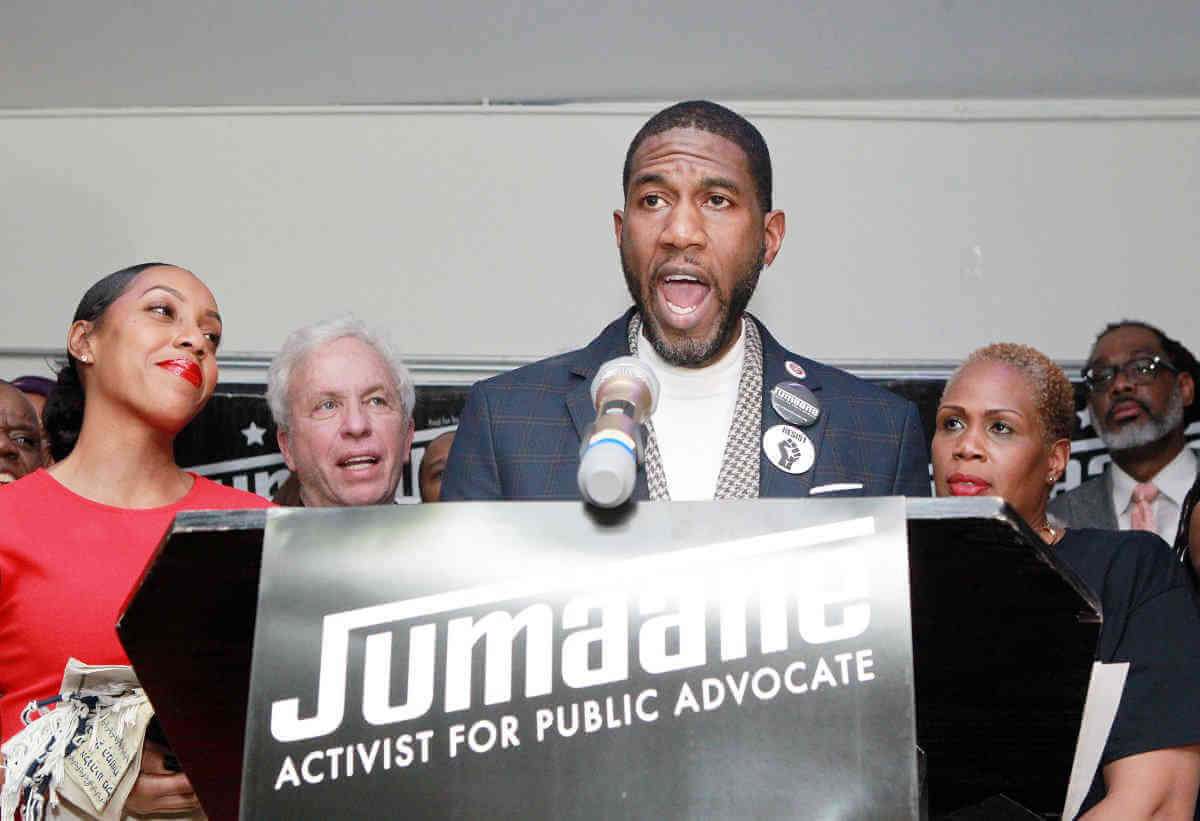

Brooklyn City Councilmember Jumaane Williams emerged from a crowded field in the special election race for New York City public advocate and won handily on Tuesday evening, capping off a contentious months-long race to fill the vacancy left by State Attorney General Letitia James.

With roughly 98 percent of precincts reporting, Williams had almost exactly one-third of the vote, with Queens Councilmember Eric Ulrich, the only Republican in the contest, garnering about 19 percent of the vote, and former Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito winning roughly 11 percent of the vote.

Just over 400,000 New Yorkers turned out for the special election, a low but not unexpected figure.

Williams, who was first elected to the Council in 2009 and has become a major voice on key progressive issues ranging from police reform to housing rights, painted himself as an activist who fits the role of public advocate because of his extensive history of standing up for marginalized groups. He has often pointed to his body of work in the Council, where, among many other laws, he led on legislation protecting people from discrimination against the NYPD and banning employers from asking about the criminal record of applicants before offering a job. He also has been arrested on numerous occasions for civil disobedience when protesting cases of social injustice.

In deeply personal and emotional remarks claiming victory, Williams said, “We have to keep going up the hill for equity, we have to keep going up the hill for justice, we have to keep going up the hill for all of us.”

He also talked about having undergone therapy for the past three years, where he learned that he was more than just the title he holds.

Williams will soon take over for Acting Public Advocate and current City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, but he has a relatively short honeymoon to savor his victory before quickly getting to work during a short term that will expire on December 31. There will be another public advocate race — a primary competition in June and a general election in November — and the winner then will serve out the remainder of James’ original second term, which runs through 2021.

The 42-year-old entered the race after garnering more than 669,000 votes in this past September’s Democratic primary in an unsuccessful bid for lieutenant governor. He performed particularly well in Manhattan and Brooklyn, where he received more than 285,000 votes to win those boroughs in his battle against incumbent Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul.

Williams’ strength across the city in that race gave him increased name recognition heading into the public advocate competition, where he quickly picked up where he left off by piling up endorsements, far outpacing his opponents. Among the many groups to endorse Williams included the Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club, an LGBTQ political group.

He faced competition from 16 other candidates on the ballot, including out gay Manhattan Assemblymember Daniel O’Donnell, who finished well back in the pack on Tuesday, and Bronx Assemblymember Michael Blake, who is vice chair of the Democratic National Committee and finished fourth. Blake showed serious fundraising prowess by hauling in more than $359,000 in contributions before counting the $838,000 in matching taxpayer funds doled out by the city’s Campaign Finance Board.

Regardless of fundraising ability or citywide office experience, those candidates were still playing catch-up against Williams and opted to target him on issues he had trouble with in the past, most notably marriage equality and abortion rights. More recently, he was hit by attacks from an outside candidate in Nomiki Konst, an investigative journalist with The Young Turks, who stood with Mark-Viverito on Monday to demand transparency about a newly-revealed 2009 incident when Williams was arrested after an argument with his then-girlfriend. The charges were dropped and the case was sealed, which led Williams’ Brooklyn colleague Laurie Cumbo to demand answers about how those sealed law enforcement records came to light.

In the first of two televised debates, Williams failed to answer inquiries from Blake and Mark-Viverito about his history of opposing same-sex marriage — even as he emphasized his support today for a woman’s right to choose — raising more questions about his handling of issues he says have been long settled.

And earlier in the campaign, Gay City News had reported that both Williams and Mark-Viverito misled members of the Stonewall Democratic Club of New York City by falsely claiming in that group’s questionnaire they had never donated to or endorsed an anti-LGBTQ candidate. In 2017, Williams donated $1,375 apiece to the re-election campaigns of Brooklyn Councilmember Chaim Deutsch and Bronx Councilmember Fernando Cabrera, both of whom are among the most homophobic lawmakers in the city.

Williams called his answer and those donations “an oversight” and said he would make a commensurate donation to LGBTQ groups.

His tricky past on LGBTQ issues also includes his 2014 abstention from a transgender rights bill that would have eased the process for people looking to change the gender marker on their birth certificate. He said he abstained because of his concerns that the measure listed midwives among those who could sign off on the change. (The need for any health professionals’ sign-off to make such a change was subsequently removed from city law altogether.)

Amid all the controversy over those positions, Williams has never voted against LGBTQ rights legislation and has worked diligently in recent years to rebrand himself as a champion for the community. In a 2017 interview with Gay City News, Williams, then vying to become City Council speaker, voiced his support for marriage equality and said his previous positions were due to religious beliefs stemming from his childhood.

By now, he boasts a very clear pro-LGBTQ platform, as evidenced by the “LGBTQ” section on his campaign’s “On The Issues” page, as well as his strong push in video advertisements and mailings to market his queer-friendly work. His Council office has allocated tens of thousands of dollars in total to a variety of LGBTQ groups over the years, including the Brooklyn Community Pride Center, Gay Men of African Descent, SAGE, and the LGBT Community Center.

He also has been a rare voice among city lawmakers to repeatedly speak out in support of transgender women of color, who he says have been “dying with impunity” at a time when they have been disproportionately affected by violence and other forms of abuse.

How Williams plans to advance LGBTQ rights in his new position is not immediately clear, but he could run into challenges in his quest to move the needle on a number of issues. The role of public advocate is viewed as significant because the officeholder is second in line to the mayor, can propose legislation, and serves as a voice for the people against the mayor and other powerful figures in government. But it is also very limited: The office’s budget is just $3.5 million, the public advocate cannot vote on legislation, and there is little other power beyond the bully pulpit.