Ed White novel follows friendship from “Mad Men” to “A Normal Heart”

BY MICHAEL EHRHARDT | Edmund White — our own professor of desire and the queer equivalent of Irish-American writer Frank Harris from a century ago — has written a fine, wise, and necessary new novel about the relationship between gay “libertine” Jack Holmes and a preppy, liberal-minded straight guy, Will Wright, that develops into a conflicted friendship enduring across three decades.

White has managed to whip up a bittersweet Nabokovian capriccio — in three parts, with an epilogue — and, as opposed to his more confessional forays, it is a genuine page-turner that is not likely to frighten any of the heterosexual horses.

“Jack Holmes and His Friend” demonstrates a similarity with his earlier work — think “Forgetting Elena” and “Nocturnes for the King of Naples” — which also involved protagonists gradually coming to terms with unfamiliar milieus and tentative identities. White is the writer who has observed, “I, a self-invented Midwestern public-library intellectual who ate books and records and art reproductions the way other people ate meat and potatoes,” and his body of work is full of unexpected observations that thicken the literary stew.

“I think it’s really interesting to talk about Foucault in one chapter and smelling poop in the basement in the next,” he has also written. “It seems to me that life is just that complicated.”

The saga of Jack and Will begins in the heady “Mad Men” era — of Jack and Jackie, just prior to the brutal implosion of Camelot — which in these grim days of economic recession, fosters a sense of nostalgia for a time of lavish expense accounts and three-martini lunches. White’s long-time fans will quickly recognize a resemblance between Jack Holmes and the author’s own semi-autobiographical middle-class Midwestern rube, adrift in an alien society — New York City — gradually learning the necessary tactics of survival in the swarming urban beehive.

Through a college connection, Jack lands a job as a staff writer for a posh, conservative culture magazine, the Northern Review, which favors employing “Ivy League snobs.” Although a fish out of water, Jack adapts handily to his position and to his female employees, but becomes slowly unglued by a new staffer and hail-fellow-well-met, Will, a gangly blueblood and would-be novelist, who serves as the unwitting catalyst for Jack to confront his own conflicted sexual identity. Although he has had sexual dalliances with women as well as anonymous male pick-ups, Jack is caught off-guard by his jonesing for this acne-ridden, flat-assed square.

White’s keen insights into the dark Eros and messy psychodynamics of frustrated sexual desire, both straight and gay, are woven seamlessly into his rich, sensuously imagined narrative.

The first part of the triptych, written from the author’s perspective, sheds light on Jack’s romantic dilemma and sequestered nocturnal sex life. As a handsome, well-endowed gay man, he makes easy conquests involving little or zero emotional involvement on his part. Although he has a sweaty sexual fling with Peter, a dancer with the Joffrey Ballet, his affable office “bromance” develops into a swoony one-sided crush on Jack’s part, as he finds himself unaccountably “mooning over a secretive straight man who wasn’t even all that attractive.”

As a friendly gesture, Will invites Jack to his parental home in Virginia, an incident that provides a good opportunity for White, a master quick sketch artist, to demonstrate his talent for conjuring up an environment in just a few telling phrases. He describes Will’s family — down-at-the-heels old rural gentry — with its faithful black retainers, fading wallpaper, and cheapskate meals (“‘sloppy joes’ and Rice-A-Roni pilaf served on a large silver bowl on which cherubs chased each other around the lip”) with an informed cinematic economy. Jack beats off thinking about Will’s naked body, “careful not to get any come on his mother’s sheets.”

He continues to desire Will compulsively, but finds him cagey and has a hard time cracking his code — until Will finally confides that he’s writing a novel, which he promises to show Jack when it’s ready for publication. This sends Jack off on an emotional tangent, imagining “that he and Will should live together, that he, Jack, should make Will dinner and suck his cock every night, that he should listen to Will’s novel once a week and praise him every time, that he should keep a low profile at work and push Will ahead. And that he should recognize that at most he’d get two good years out of Will before the young author met the right girl: witty, nearly virginal, rich, fragile, feisty on the surface but essentially yielding.

“Yes, just two years with Will, that’s all he’d ever ask for from the gods. He knew he’d never be able to mention their affair to anyone, not even to Will. But if he could nurture Will’s self- confidence, his talent, bring him pleasure, build him up, worship him! Yes, he’d worship Will’s body, never expect anything more than an occasional hand tousling his hair… Just to know that Will would come bounding in the door, whistling, and sit down to dinner and eat with all the unquestioning sense of privilege of a real man, just as he’d stretch out on his bed and pretend to be asleep and let Jack measure all known distances from the milliarium aureum: that was Jack’s dream. It wasn’t that he was queer; he just loved Will.”

Jack’s love-sick “malady” was treated by White in his fanciful 1985 roman à clef, “Caracole,” in which the protagonist finds himself in a similar dilemma, but over a woman: “Love is a progressive illness, one that starts as self-hallucination, an act of parody, and ends as a wholly real, involuntary malady that kills us or something vital in us. Mateo could never quite understand when or why he’d fallen so terminally in love with Edwige, but he suspected that whereas when could be answered, as least theoretically, why could not.”

Yet, Jack can’t stop fantasizing about Will. “… when he started jerking off, all he could think about was sucking Will’s cock. He’d never sucked a cock. He wished he’d paid more attention to what that Edward guy had been doing to him. Maybe he should go back and take lessons. How sick is that, Jack said to himself over and over again. He had a fistful of come that he licked away like a cat — he was too tired to get up to find a tissue. He decided that the bizarre events of the day had pushed him too far, into this dangerous territory. He promised himself he’d never again jerk off over Will (or any other guy). New York was doing weird things to him.”

Jack, yearning for the unattainable, suddenly finds Peter a turn-off, deciding that “everything about this man-boy-girl seemed obscene… his drag queen delusions of grandeur… his unappeased narcissism — he was a walking, leaping, undulating formula for unhappiness. He preferred Will’s cold, uncaressed body, vague and pale and almost inert inside his baggy clothes… Jack preferred Will’s inaccessibility to Peter’s constant presence… preferred daydreaming about the life he might lead with Will. He liked to imagine what Will’s body would feel like and how it might respond rather than to know all too well how Peter’s functioned. Real sex was all too meaty, too medical, as if sex plunged you into all the pulsing, sweating systems, the nerves and valves and secretions, whereas imaginary sex remained speculative, spiritual, indeterminate.”

Eventually, Jack sees a shrink and makes a clean breast of his pent-up feelings to Will, who, although genuinely nonplussed, is flattered by the ardent admission, even though such ardor is alien to his straight viewpoint.

The novel’s second section is a first-person account, narrated by Will, who has given up writing after the critical fiasco of his first try and married the wealthy, patrician Alexandra, whom he’s met through Jack. The couple has moved to a house on 25 wild acres in Larchmont, New York, mostly subsidized by Alexandra’s father. Will has fathered two children and works at a soul-less job writing annual corporate stockholder reports. Jack is now a financial reporter at Newsweek.

Soon, Will, living a life of quiet desperation, devoid of erotic spark, and fed up with a sterile job, succumbs to a midlife crisis. He becomes involved in a heated affair with Pia, a younger, seductive jetsetter he also meets through Jack. Meanwhile, Jack has become a social gadfly and walker of wealthy women of a certain age, and now lives in a two-bedroom flat, which he obligingly furnishes to Will to conduct his illicit trysts. The ever-enthralled Jack can now drill Pia for information about Will’s amatory skills, while living vicariously through her.

When Will’s inbred Catholicism results in pangs of guilt over his illicit love for Pia, she leaves him. However, once again thanks to Jack’s assistance, Will takes up with Amy and joins the fellowship of libertines. If a stiff cock has no conscience, neither does a jealous heart. Forced to spiritualize his unrequited desire, Jack places Will’s marriage in jeopardy, while betraying his friendship with Alexandra. (Is this a self-justifying set-up on Jack’s part to sabotage Will’s marriage and land him back in his orbit? White leaves that pretty much up to the reader to decide.)

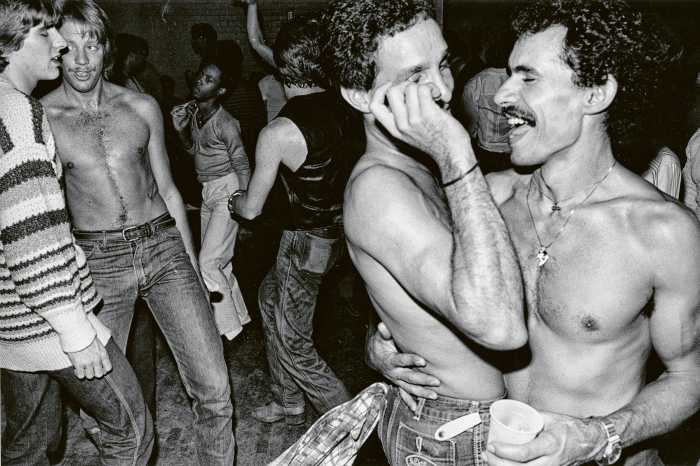

The cold-blooded Jack is not all that likeable, but he is, after all, all too human. This section ends just as the golden Aquarian Age of free love is threatened by the dawning era of AIDS.

Leave it to White — the most Gallic-influenced of American authors — to write so convincingly about the joys and douleurs of an amour fou. All this is written in a sensuous prose that extends from the intimate details of gay sex (“gazing at Peter’s ass with angelic indifference, to spreading his cheeks and grazing his hole with his thumb and bringing it up to his nose with canine rapture. He thought that the blend of patchouli and boy mud was the most intoxicating scent, the true smell of modernity… [T]he smell of the sixties, ass and incense”) to the insular bitchiness of the ballet world and the Mies-inspired glamour of the Four Seasons restaurant (“The ceilings were high, the napery dazzling, and the windows hung with long, fine gold chains echoed by the chandeliers… [Pia] shone like an ingot in the bank-like majesty of this room; the light outside just faded, and the gold bead curtains came to life, strafed by the electric lights projected up onto them”.

The novel ends with a lovely coda — a Rosenkavalier “jaja” moment — about ten years afterward. Jack has journeyed a wide arc from self-loathing to self-acceptance, while Peter has become a casualty of the plague, and Jack, in a steady relationship with an older, successful theater director, meets up with Will, along with his stage-struck teenage son, Palmer. White hints that Jack and Will are likely to remain friends well into the future.

Essentials:

JACK HOLMES AND HIS FRIEND

By Edmund White

Bloomsbury USA

$26; 400 pages