Joe Nicholson at the New York Post in a 1999 photo. | VERONIQUE LOUIS

BY ANDY HUMM | Joe Nicholson, who came out as a reporter at the New York Post in 1980 –– a first for anyone at a big city daily –– died October 8 after a battle with cancer. He was 71 and is survived by his beloved Sherwin T. Nicholson, whom he married in January 2013 at Holy Apostles Church in Chelsea and where his funeral was conducted on October 11. The men had been together since 1982.

Nicholson started at the Post in 1971 under the liberal ownership of Dorothy Schiff, but came out in 1980 under the conservative Rupert Murdoch regime, partly in response to the shootings at the West Village bar Ramrod by a deranged anti-gay killer who felled two gay men and wounded others. Nicholson wrote a story for the Post about how such violence is driven by homophobia and published it in the New York Native, a gay weekly, after the Post spiked it.

Nicholson wrote that Murdoch’s editors from Australia and Britain “arrived accepting stereotypes they had heard about homosexuals, and so I thought they should get to know an actual gay man who had been a standout player in high school football, a college rugby player, and a Navy officer, things I don’t think most of any of them had been. I have to say they responded magnificently and gave me some of their best assignments.”

Post veteran, first out out reporter at a city daily, made mark in AIDS, hate crime, St. Pat’s stories

“Joe was not only a tenacious tabloid reporter, he was a really sweet guy and completely adored Sherwin,” said longtime gay civil liberties activist Bill Dobbs. Indeed, the journalistic exploits of Nicholson, who spoke fluent Spanish, included jumping into the back of Fidel Castro’s car in 1973 to get an exclusive with the Cuban leader. His 1973 book, “Inside Cuba,” was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

Nicholson reprised the car tactic years later in pursuit of State Senator Roy Goodman, a mostly liberal Republican from the Upper East Side who was opposed to the state hate crimes bill. Nicholson’s impromptu back-seat questioning of Goodman eventually got him to come out in favor of the long-delayed legislation, gaining the measure a sponsor in Senate majority party. The bill finally did pass in 2000, after an 11-year battle.

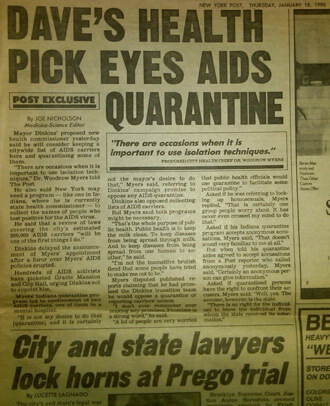

Joe Nicholson’s front-page story about the proposal of Mayor David Dinkins' health commissioner nominee, Dr. Woody Meyers, to quarantine some people with AIDS. | NEW YORK POST

As medical-science editor of the Post in January 1990 in some of the worst years of the AIDS pandemic in New York, Nicholson exposed Mayor David Dinkins’ nominee for health commissioner, Dr. Woody Myers, as someone open to quarantining gay people if necessary. Myers, an African-American Republican from Indiana who had served on the Reagan AIDS Commission that was stacked with conservatives such as Cardinal John O’Connor, told Nicholson, “There are occasions when it is important to use isolation techniques.”

“LOCK UP SOME AIDS CARRIERS,” the Post’s front-page blared with a picture of Myers, throwing a wrench into his nomination put forth by Dinkins transition team members including Gay Men’s Health Crisis’ Tim Sweeney, Dr. Mathilde Krim of the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and Tom Stoddard of Lambda Legal but militantly opposed by ACT UP.

The New York Times essentially urged Dinkins to stand up to ACT UP, writing, “It would be naive to suppose that Dr. Myers’ likely policies in New York can be inferred from his policies [in Indiana].” Myers recanted his position on quarantine, but served just a little over a year in the position.

Nicholson’s reporting on AIDS won a 1992 award from the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, the media watchdog group that ironically was formed in 1985 in response to the Post’s sensationalistic coverage of the early epidemic.

Joe Nicholson’s story about Dr. Woody Meyers. | NEW YORK POST

A series Nicholson wrote on medical do-not-resuscitate orders for the Post moved State Health Commissioner David Axelrod to put forth and get passed a law that such orders be required to be in writing. The series was nominated for a Pulitzer.

Nicholson also brought major newspaper attention to the quest of the Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization to march in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in 1991. I was a Dinkins appointee on the City Human Rights Commission at the time and Nicholson quoted me saying that if ILGO could not march, the mayor should not either. That, too, landed on page one and fueled the controversy, leading to ILGO marching without its banner but with Dinkins among its contingent, which was met by a chorus of boos and occasional beer-can missiles. ILGO was banned thereafter and Dinkins boycotted the subsequent exclusionary parades.

When President Bill Clinton’s promise to lift the ban on open gay service in the military was scuttled by adoption of the 1993 Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy, Nicholson wrote in the Post about his time as a closeted Naval officer and later talked about his experiences on Charlie Rose and Phil Donahue’s TV programs.

After 22 years at the Post, Nicholson moved over to the Daily News and later became an associate editor at Editor & Publisher.

Nicholson was a generous mentor to other journalists. Veteran out journalist David France, who directed the Academy Award-nominated documentary “How to Survive a Plague,” wrote, “Joe taught me to be a reporter” and called Nicholson, among other things, “aggressive, thorough, fair” and “wicked, fearless, generous, and full of love for truth and justice.” He also wrote that Nicholson “snuck me into a job” at the Post “where I worked with him for 89 days. He was amazing to watch up close.”

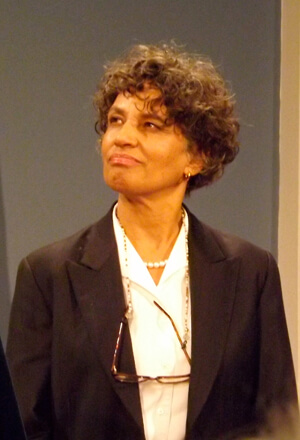

Sonia Reyes was an administrative assistant to Post editor Roger Wood. At Nicholson’s wake at Redden’s Funeral Home, she told me, “The only reason why I became a reporter was because of Joe, Joe, Joe. He had a vision for me that I didn’t have for myself,” lobbying her for two years to get into reporting. She became the first Latino reporter at the paper and said she learned her craft from Nicholson.

“I’m attuned to bigotry,” Reyes said. “Joe had to fight the editors to get his stories on AIDS in. He was so thorough that they finally broke down and published them.”

Nicholson’s cousin, Michael Lane, eulogized him, citing his many achievements as a reporter and his journalistic mantra, “Just get it right.” But Lane said, “His biggest achievement by far, though, was his 32 years with the love of his life, Sherwin.” Lane said to Sherwin, a tall, soft-spoken Trinidadian immigrant who found love with the shorter Irish American Nicholson, “You are the best thing that ever happened to our family.”

Joseph H. Nicholson, Jr. was born July 13, 1943, the son of a reporter and Associated Press executive, Joseph Nicholson, and a teacher, Virginia, who predeceased him. He was a graduate of Bronxville High School and Holy Cross College, and began studies at Fordham Law School before turning to journalism. In addition to his husband, Sherwin, he is survived by a sister, Katherine Nicholson Pendergast of Belmont, Massachusetts, niece Elizabeth Pendergast, and many cousins including Lane of Brooklyn, Timothy Muller of Manhattan, and Mary Anthea Muller of Greenport on Long Island.

Donations in Joe Nicholson’s memory can be made to Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen at 296 Ninth Avenue at 28th Street, the city’s largest voluntary meals program for the homeless.