BY PAUL SCHINDLER | Yarden Noy, a 26-year-old finishing up his law studies at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University while he works at Israel’s Ministry of Justice, didn’t join that city’s LGBT Pride Parade because he is gay. Nor was he there to join an LGBT family member or friend. Instead he met up with several friends who are also straight to show support for a community that many in Jerusalem still consider “taboo.”

What happened to Noy that day has made him into an LGBT ally advocate.

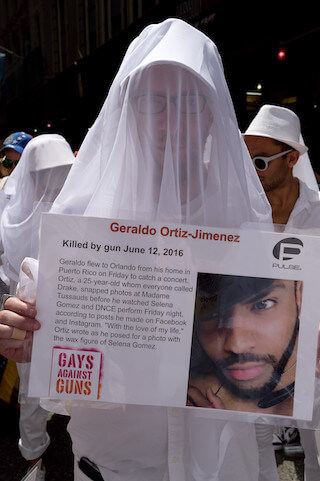

Noy was one of six people stabbed during the July 30 parade, allegedly by an ultra-Orthodox Jewish man released from prison just three weeks before, after a 10-year sentence for a similar crime in 2005. Yishai Schlissel, 39, has now been charged with murder because one of the stabbing victims, 16-year-old Shira Banki, died from her wounds.

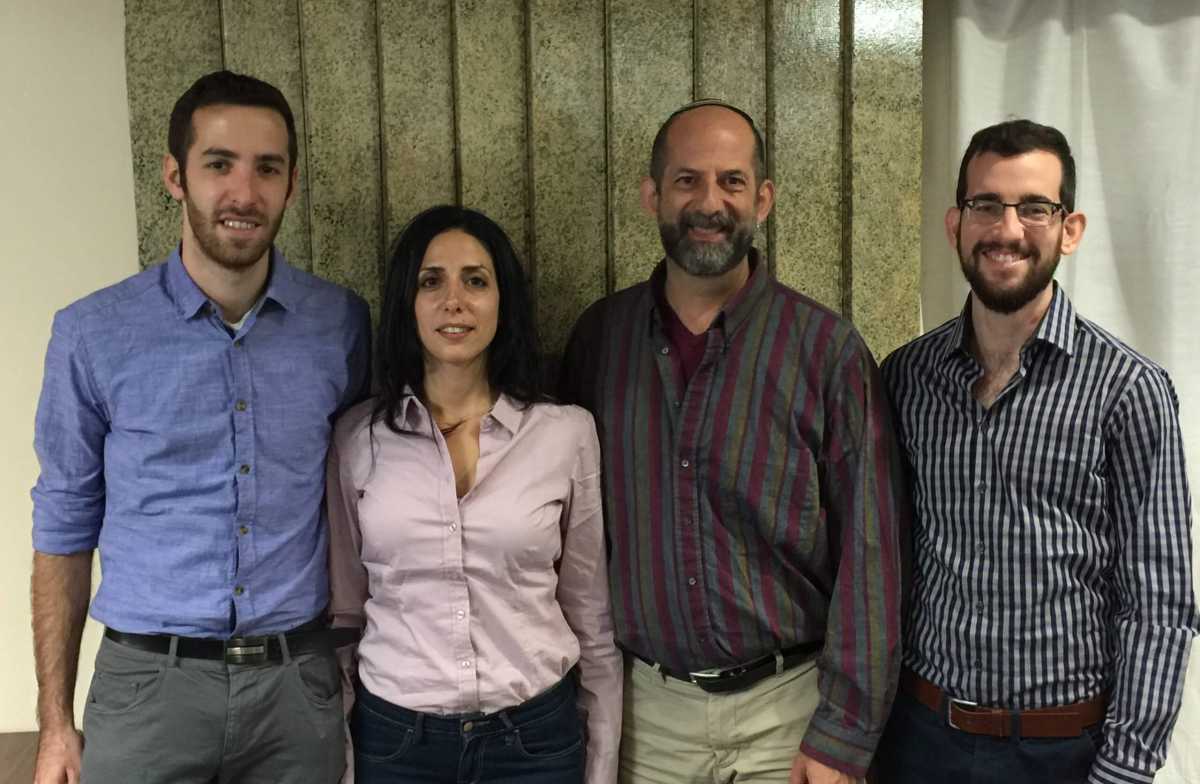

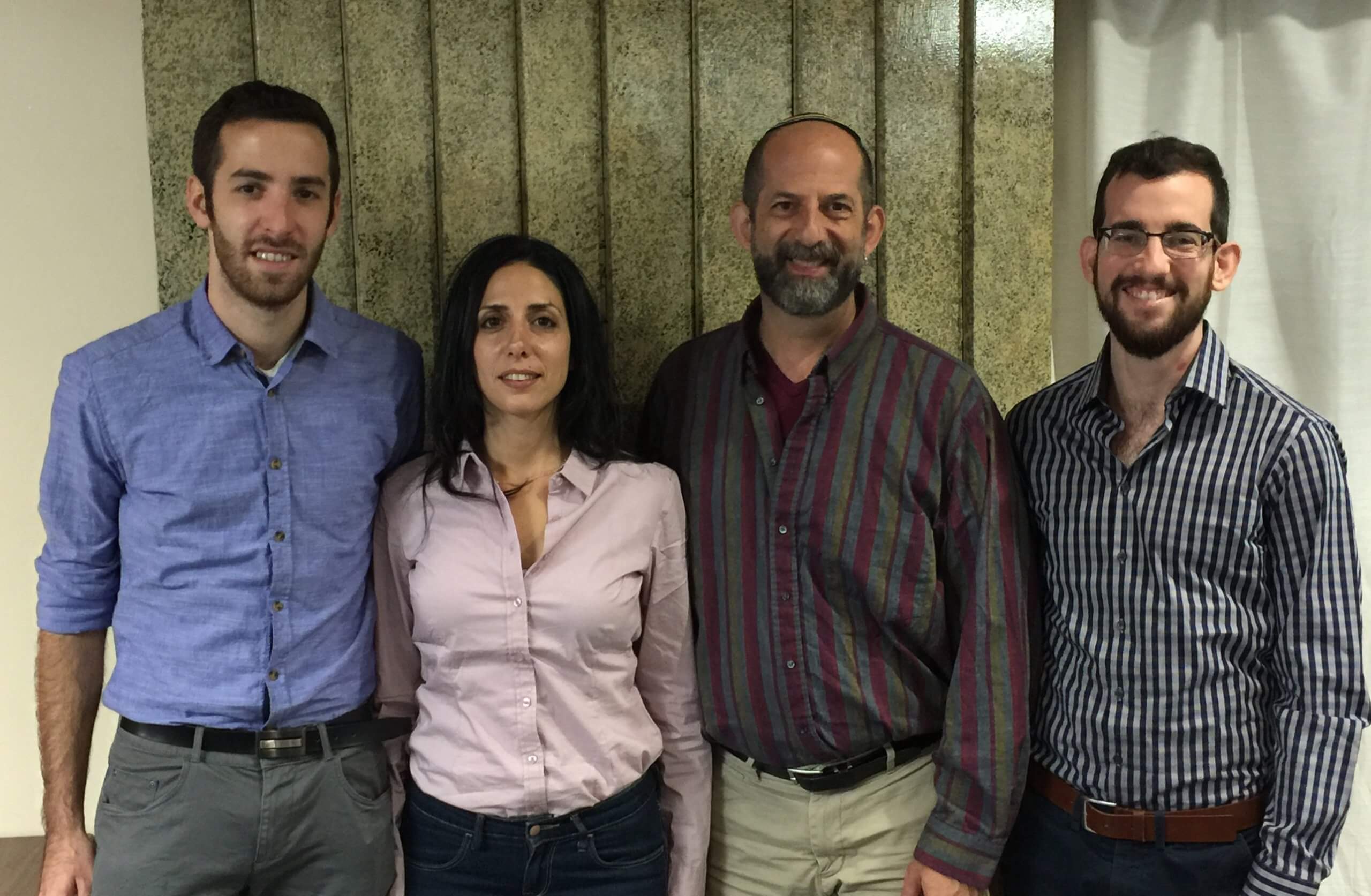

Noy, stabbed in the back, suffered damage to his ribs and lungs and spent five days in the hospital. During a September 21 interview at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, New York’s LGBT synagogue on Bethune Street, where he was visiting along with two leaders from the LGBT-focused Jerusalem Open House for Pride and Tolerance, Noy reported that he was “almost back to normal.” For several hours after the attack, however, his “life was at risk.”

During his hospital stay, Noy was visited by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, by Orthodox Jews who apologized for what Schlissel is said to have done in the name of religion, and by members of the Open House.

Visits from Open House members, including its executive director Sarah Kala and its development director Tom Canning, both of who joined him on his New York visit, had a profound impact on Noy’s life.

“Before the parade, I was not connected to the community,” he explained. “After the parade, I began to know the LGBT youth who meet at the Open House.”

The Open House’s work with youth is one of its principal missions.

“We are saving lives every day,” Canning said, explaining that there is no such thing as sex education in Jerusalem. Referring to the predominance of Orthodox Jews in that city, he added, “These questions cannot be raised in many families.”

The Open House has the only anonymous HIV testing clinic in the city, and it serves not only gay and bisexual men, but also sex workers and others.

Canning said it is important to understand that Tel Aviv — the Mediterranean coastal city known for its nightlife and warm embrace of gay and lesbian tourists — is “not the real Israel.” In Jerusalem, he said, the LGBT community faces rejection from not only Orthodox Jews, but also the Palestinian community as well as culturally conservative but more secular Jewish residents.

“The idea of the LGBT community in Jerusalem is still taboo,” Canning said.

In fact, the risk of boycotts from the Orthodox community prevents corporations from giving financial support to the Open House. The group’s fundraising, Canning explained, is focused primarily on Jewish LGBT communities in North America.

In Noy’s view, the antipathy toward LGBT Israelis in Jerusalem contributed to the climate in which the stabbing took place. Referring to Schlissel, the alleged stabber, he said, “He is the head of the pyramid. He wouldn’t do it if he didn’t feel support. It is the environment, the opposition to the parade and to the gay community that are responsible.”

Despite the tough climate in which the Open House does its work, Canning explained, “Jerusalem has changed.”

“If you think about Pride a decade ago, people were throwing dirty diapers and urine at us,” he said. “Since the stabbing we have tried to engage with ultra-Orthodox leaders at the highest levels and have asked them to condemn violence.”

In what Canning and Kala described as an unprecedented development, Israeli’s chief Ashkenazi rabbi, David Lau, spoke at a rally organized to condemn the stabbings. Though he made clear he opposed the Pride Parade, the rabbi, Canning said, “took a big risk… and that’s important.”

Out of the July 30 tragedy, the Open House is identifying inroads for dialogue with people the group was never before able to engage. As Kala sat with Gay City News, she received an email saying that for the first time, the Open House was invited to meet with students at an Orthodox school — this one for girls — to discuss an LGBT educational program developed by Orthodox LGBT activists.

“The Orthodox community took the stabbings very hard,” Canning said. “They are very conflicted. They don't support Pride, but are horrified at the thought of someone doing this in the name of God.”

In the days after the stabbings, Noy was vocally critical of the police.

“It is clear the police were negligent,” he said, and pointed to an official law enforcement report that came to the same conclusion. Authorities were aware that Schlissel was out of prison and was speaking out in inflammatory language about the parade, but they acknowledged he was not placed under surveillance during the weekend it took place.

Canning said the Open House had worked closely with police authorities in the months leading up to the Pride Parade. The problem was not antagonism toward the LGBT community — though in years past the Open House had an adversarial relationship with police — instead Canning explained it was a problem of “implementation.”

In a climate where showing support for the LGBT community can result in ostracism from Orthodox quarters, Canning said, “For us, it’s a very strong message to have Yarden with us and have straight allies march with us. People will think, ‘Why don’t they come out? Is the problem with me? Why don’t I come out?’”

As the LGBT community learns all over the world, visibility is key to progress.

Asked whether there was particular significance in Noy, Canning, and Kala visiting Beit Simchat Torah during Yom Kippur, Canning responded, “On a personal level, we've have had a difficult two months. We hope this will mark an end to that, a change of pace, to start the new year on a positive step. Yom Kippur involves a big element of self-reflection that’s appropriate regarding our work and our society.

Rabbi David Dunn Bauer, who is the director of social justice programming at Beit Simchat Torah, amplified on that thought. Noting that the congregation’s Yom Kippur services draw a huge crowd to the Javits Center every year — a crowd that the Israeli visitors would speak to on September 23 — he said, “At CBST, we have an experience that can’t be had anywhere else. To feel the love of 4,000 LGBT people and our allies. You won’t have that experience anywhere else in the world. We wanted to offer healing. It is something quite remarkable. The sense of community is so strong, and the commitment for a better year is so strong.”

Recalling the visits he received in the hospital from Orthodox Jews voicing their distress about the stabbings, Noy, whose body is healing, reflected on the care of his soul. The arrival of strangers offering their sympathy for the pain he endured, he said, was “heartwarming and encouraging.”