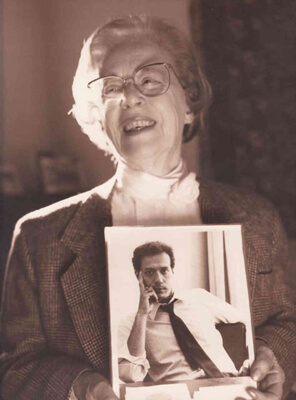

Jeanne Manford holds a photo of her son Morty, shortly after his 1992 death from AIDS.

Jeanne Manford, who died January 8 at the age of 92, is being hailed around the world for the simple but radical concept she put into action in the early 1970s — parents of LGBT people helping each other to accept their children and get over their own upset about their kids’ sexual orientation.

Her co-founding of what was then called Parents of Gays grew out of her fierce devotion to her gay activist son, Morty Manford. And the intensity of that devotion — it has now come to light — was likely due to the fate of her other son, Charles, who died before she and Morty became activists.

What has also been missing from most of the tributes to Jeanne Manford is the key role her son’s pioneering group, the Gay Activists Alliance, played in the founding of Parents of Gays (POG, but now the Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays or PFLAG).

Ethan Geto, 69, himself a legendary gay activist and one of the city’s leading political consultants, was very close to the Manfords, and Morty came to live with him in Manhattan after he left the family’s home in Queens in the early 1970s .

In 1966, Morty’s older brother Charles “committed suicide,” Geto said, “and it was pretty apparent from my closeness to Morty and Jeanne that he did it because he couldn’t cope with his increasing recognition that he was gay. It is an important factor that is never mentioned. When Morty came out to his parents, Jules and Jeanne, their reaction was, ‘I am not going to lose another son because this society is so prejudiced against gay people. I want my son to thrive.’ She was instantly supportive. Jules came around — and quickly.”

Shortly after Charles’ suicide, Morty — himself depressed at 15 — asked his parents if he could see a therapist. The second therapist he saw told the Manfords, to Morty’s dismay, that their son was homosexual.

Geto said, “Her first reaction was to get him the help that he needed — not to change him, but to make sure he was okay. She wanted to do something. Her attitude was, ‘I cannot let happen to Morty what happened to Charles — I have to do everything I can in my own little way to change society.’ It turned out to be in a big way.”

Having lost one son, she turned love for his brother Morty into worldwide parent support group

Morty soon became a pre-Stonewall activist, involved with the formation of the gay group at Columbia University in 1968. He participated in the Stonewall Rebellion in 1969 and soon became a leader of the Gay Activists Alliance.

Steve Ashkinazy, a fellow member of GAA, remembers the Manfords as so supportive of their son that when Morty was living at home with them, “he could bring tricks home and Jeanne would serve them breakfast in the morning.”

Geto said that “Jeanne was a kind of first den mother for many of those who had been kicked out of their homes — with parents like Amy Ashworth ‘honorary moms’ for gay activists on the front lines.”

Allen Roskoff, a GAA pioneer whose own parents shut him out when he told them he was gay, said that when Jim Owles, the group’s first president, ran for City Council in 1974, “one of the things Jim had neglected due to his movement activities and finances was to provide proper care to his teeth. Jeanne Manford’s husband was a dentist and had an office in their Flushing, Queens home. At Jeanne’s insistence, Jim and I would trek out to their home on Saturdays and Jim had his teeth cared for in time for campaign photos.” Many early activists depended on Jules for no- or low-cost dental care. (Roskoff, a co-author of the nation’s first gay rights bill in New York in 1971, is now president of the Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club.)

It was Jeanne’s motherly affection for her son and Morty’s comrades that led her to go public in 1972, when Morty was physically attacked while engaged in a GAA zap aimed at the Inner Circle press dinner that attracts the city’s political establishment annually. Morty was kicked and stomped there by Michael Maye, head of the firefighter’s union and one of the leading opponents of the city’s gay rights bill. Following press coverage, Jeanne wrote a letter published in the New York Post defending her son and attacking the police for standing by and not doing anything about it.

In the 1972 Christopher Street Liberation Day march commemorating the third anniversary of Stonewall, Jeanne marched with her son and daughter, Suzanne, carrying a sign that read: “Parents of Gays Unite in Support for Our Children.” In a famous photo of that bit of history, Dr. Benjamin Spock, author of the best-selling books on caring for newborns, can be seen behind Morty, and the Manfords thought the intense cheering they heard from the sidelines was for him. But as it has been every since, it was a mother and sister stepping up to march for their son and brother who were receiving the heartfelt thanks from a community where so many have suffered family rejection.

Even before they conceived of a formal group for parents, Geto said, Jeanne Manford and Amy Ashworth “were reaching out to a handful of parents on the phone at the instigation of their sons, Morty and Tucker. They would tell them, ‘We went through the same thing’ and would say, ‘You don’t have to lose your child, you can still have a relationship with them.’”

In late 1972, Geto was part of a meeting with the Manfords, Dick and Amy Ashworth, their son Tucker, and Bob and Elaine Benov at the Metropolitan Community Church, which then met at the Metropolitan-Duane Methodist Church on Seventh Avenue at 13th Street.

“They said, ‘We’ve got to form an organization. We need to reach other parents,’” Geto recalled. “They turned to me as a PR maven. Jeanne was a very, very driving force there. From her came this whole spirit of ‘we have to do more.’ There were all these people with troubled relationships with their families. Parents were suffering and the kids were. From that day forward, she worked hard and organized. Would call parents cold when she learned they had a problem. ‘We don’t want to intrude,’ she’d say, ‘but we can help.’”

Parents of Gays met in early 1973 as a self-help support group and blossomed into what it is today, an international organization with hundreds of local chapters.

Ashkinazy felt that Jeanne became the activist she did because Morty wanted her to. “POG was Morty’s idea, a new grassroots approach to activism involving allies and parents,” he said. Indeed, GAA spawned many other movement groups, including the Gay and Lesbian Independent Democrats, founded by Owles, and the Chelsea Gay Association that in turn led to the formation of the Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project.

Willy Jump, 77, active in the parents group for more than two decades, said Jeanne “was an incredible woman. She started it all.” Her son, Frank Jump, 52, said, “I remember marching every year in the parade with Morty and Jeanne and Jules and my Mom. They always got the warmest welcome from the crowd. People would run up to her and fall to their feet and cry. She was an icon for a lot of young gay people back then. Jeanne never had a problem with Morty.”

Jeanne was also the founder, in 1993, of the Queens chapter of PFLAG with gay activist Daniel Dromm, now a City Council member, “because as she grew older she wanted to be able to continue her gay activism closer to home in Flushing, New York where we both lived,” Dromm said in a release. “Her activism over the last 40 years and the founding of PFLAG have changed the way that parents and their LGBT children relate.”

The Queens chapter presents the Morty Manford Award to a worthy activist each year.

In 1991, Jeanne was grand marshal of the LGBT Pride Parade in Manhattan and, in 1993, grand marshal of the first such parade in Queens. At the 30th anniversary dinner of PFLAG in 2003, Jeanne, Amy Ashworth, Elaine Benov, and Edie Ogolsky were presented with the “Fearless Pioneers Award” by the national group.

Jeanne Manford once told gay author Eric Marcus, “I’m very shy, by the way. But I wasn’t going to let anybody walk over Morty.”

That attitude was on display shortly after Morty’s death from AIDS in 1992. I was then director of education at the Hetrick-Martin Institute for LGBT youth, and I joined her to discuss youth issues on Geraldo Rivera’s television show. Over our pre-show objections, Rivera inserted the psychologist Paul Cameron — whose theories linking homosexuality to child sex abuse had already been discredited by his professional peers — into the program. When Cameron began to attack Morty, saying his homosexuality caused his death, Jeanne rose up like a mother lioness and screamed at him, not allowing him to continue with his calumny.

Geto said that “at the end stages of Morty’s illness, he lived at home, refusing to be hospitalized. He slept on a bed downstairs in the living room — not out of the way in a bedroom upstairs — with IVs, right there when you came into house with people coming and going. His mother insisted. She wanted to take care of him personally. She really masked her grief and horror and when I would come to visit, she was so upbeat and pleasant. It was the most difficult act any performer could perform because her heart was melting away. He wanted to be at home and his mother wanted him at home. Her devotion was there to the last day.”

Jeanne Sobelson Manford was born December 4, 1920. She graduated from Queens College in 1964 and was an elementary school math teacher at PS 32 in Queens for 26 years, retiring in 1990 at age 70. Her husband, Jules, died in 1982. She is survived by her daughter, Suzanne Swan, one granddaughter, and three great granddaughters. She moved Rochester, Minnesota, in 1996 to be near her family and later to Daly City, California. That is where she died of natural causes, according to Swan.

Jody Huckaby, PFLAG’s national executive director, said in a statement, “Jeanne Manford proved the power of a single person to transform the world. She paved the way for us to speak out for what is right, uniting the unique parent, family, and ally voice with the voice of LGBT people everywhere.”