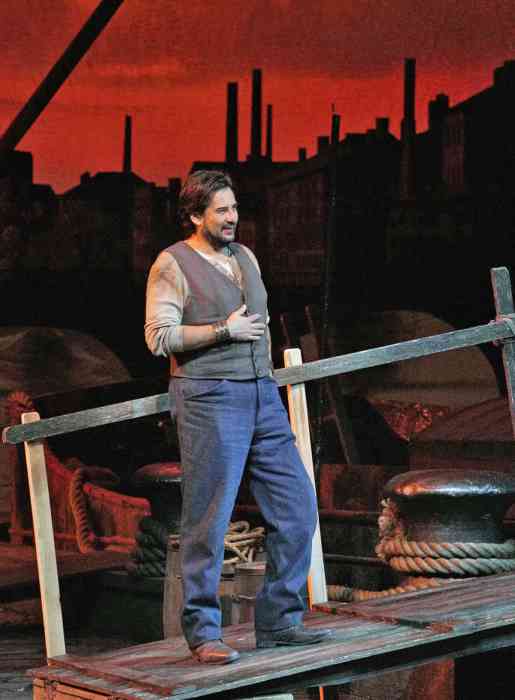

Piotr Beczala and Anna Netrebko in Tchaikovsky’s “Iolanta.” | MARTY SOHL/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Washout though it was, at least in New York City, winter storm Juno claimed at least one victim with the cancellation of the January 26 Metropolitan Opera double bill of Tchaikovsky’s “Iolanta” (1892) and Béla Bartók’s “Bluebeard’s Castle” (1918). The postponed premiere took place on January 29 with drama onstage and off. During the curtain calls for “Iolanta,” starring soprano Anna Netrebko and conductor Valery Gergiev, a protester calmly climbed on to the stage from the auditorium left. Standing downstage center in front of the assembled cast, he unfurled a banner denouncing Russian President Vladimir Putin for his country’s recent military aggression in Ukraine. The banner had an image of Putin pictured as Hitler, along with photos of Gergiev and Netrebko, who were denounced for their political collusion with the Russian leader. The man silently displayed the banner to the audience and then the performers while the well-heeled audience, including many Russian émigrés, booed. He then calmly walked offstage right, where he was promptly detained by security and later arrested. Similar demonstrations faced Gergiev earlier in January when anti-Putin/ pro-Ukrainian protesters gathered outside BAM during the Maryinsky Ballet’s residency there. Netrebko has deleted her Facebook page due to personal attacks from disillusioned fans.

The two works that comprised the double bill have very little in common except a heroine’s desire to emerge from darkness into light. Tchaikovsky’s blind princess Iolanta is rewarded for her faith and love with the gift of sight, both spiritual and physical. But in Mariusz TreliÅ„ski’s production of “Bluebeard,” Judith’s curiosity brings her eternal imprisonment in darkness. “Iolanta” was a Met premiere, while the Bartók has been performed in two previous productions, but in English translation. January 29 marked the first performance in its original Hungarian.

TreliÅ„ski updated both works to the mid-20th century, citing 1940s film noir and Hitchcock as influences. “Iolanta” took place not in a medieval castle garden but in an isolated mountain hunting lodge where Princess Iolanta is kept in seclusion so she can never know she is unlike others. Netrebko created a moving heroine who knows her life is missing something essential but doesn’t know what it is. Vocally, she was careful not to oversing but the girlish brightness and liquid ease were gone. It was a darker, thicker sound that favored louder dynamics and could sag below pitch. This new mature voice was effective as Verdi’s Lady Macbeth but lacks the innocence and youthfulness for Tchaikovsky’s sheltered maiden.

Met’s delayed “Iolanta”/ “Bluebeard’s Castle” premiere yields drama, surprise winner

Piotr Beczala’s silvery tenor as her savior Vaudemont was like a beam of sunshine in the darkness. His smile lit up the stage and he floated a beautiful heady piano high note at the end of his entrance aria. Their love duet brought down the house. Baritone Aleksei Markov sang Robert’s big aria handsomely if too loudly, and he and Gergiev seemed slightly out of sync.

The rest of the cast was less gala. Cover artist Ilya Bannik stepped in as King René, and he looked too young and his voice proved too slender and short at the bottom for a classic booming Russian bass role. Debutant Elchin Azizov as the Moorish physician Ibn-Hakia revealed a firm but dry-sounding bass-baritone that lacked authority and mystery. Matt Boehler as Bertrand fielded the most impressive deep voice onstage.

Gergiev, outside of “Queen of Spades,” has never impressed me as a natural Tchaikovsky interpreter — the ravishing score lacked lyric impulse and warmth. TreliÅ„ski’s update seemed self-conscious and rather jejune at times — especially during the finale. The entire cast assembled in a line downstage dressed in white wedding outfits and posed as if for a wedding portrait while a phony looking sunburst was projected in the background. Tchaikovsky’s music for this happy ending is sincere and uplifting, but the director seemed to be ironically smirking at all the naïveté.

USE JACOBSON bluebeard – Michael & Petrenko IS.jpg Nadja Michael and Mikhail Petrenko in Bartók’s “Bluebeard’s Castle.” | MARTY SOHL/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Both director and conductor were more in their element in “Bluebeard’s Castle.” Gergiev summoned brooding, dark, creepy power from the Met orchestra. TreliÅ„ski’s direction and Boris KudliÄka’s shifting sets evoked not so much Hitchcock as Kubrick’s “The Shining” and Resnais’ “Last Year at Marienbad.” The images were disturbing not for what they showed but for what they didn’t show — until Judith opens the final door. The last scene was so haunting, harrowing, and unforgettable it blew away any previous reservations I had about the production.

No great or even good voices were to be heard here — but both Mikhail Petrenko and Nadja Michael inhabit the production fully. Petrenko has chilling blue eyes and uses stillness effectively while Michael, with her platinum blonde hair and lithe frame (briefly seen topless), writhes about the stage with uninhibited abandon. Petrenko’s bass is an empty-toned, small instrument — even when miked offstage. Michael only managed to summon consistent tone, line, and pitch at the very bottom of the contralto range — anything higher was pitchy, patchy, and ugly. Her acting tends to be externalized, all kinetic energy and generalized intensity. Judith’s vulnerability and defiance didn’t reveal themselves from within — until the final scene. It is impossible, however, to take your eyes off of her. Despite the less stellar cast, “Bluebeard’s Castle” was the real triumph of the evening.

“Iolanta” and “Bluebeard’s Castle” will be transmitted in HD on February 14 at 12:30 p.m.