Two shows set in the first decade of the 20th century are delighting and illuminating audiences. At the Donmar (to Feb. 7) is “When We are Married” by J.B. Priestley (1894-1984), a precursor to sitcoms if there ever was one. Written in 1938 but set in 1908, three upstanding couples are celebrating their mutual 25th wedding anniversaries, only to learn that the priest who performed their ceremonies was not certified to do so — giving them all pause about whether they really want to be married to their spouses. Tim Sheader, fresh from running the big Open Air Theatre in Regents Park, directs this company of comic pros to fire on all cylinders in the intimate Donmar. All are fine, but special kudos to Sophie Thompson as a wife who has really had it with the strictures of her role; Janice Connolly as Mrs Noirthrop, the sassy but upright maid; and Ron Cook as the inebriated photographer.

For all the mirth and mayhem, there is a lot to chew on here about marriage, especially as it constrained women at the time it is set in when to actually be divorced was to be cast from polite society. Priestley was writing just after King Edward VIII had to give up his throne in 1936 to marry the thrice-divorced Wallis Simpson.

“Playboy of the Western World,” John Millington Synge’s 1907 comic masterpiece directed by Caitriona McLaughlin, is on the big Lyttleton stage at the National until Feb. 28. It stars Éanna Hardwicke as Christy Mahon in the title role; Nicola Coughlon as the no-nonsense Pegeen Mike, the barkeep who nevertheless falls for him; and Siobhan McSweeney as the formidable Widow Quinn, who also has her eye on Christy — with a great cast of Irish actors in supporting roles who take us into the constrained world of impoverished, occupied Ireland. Christy comes not with some political vision but with a tale of having killed his own oppressive father — told in such a way that makes him glow with celebrity and make women fight over him.

While challenging, there is no compromise with the lyrical Irish dialect in which Synge wrote “Playboy.” This is a darker take on the play. Past productions that I’ve seen feature the slapstick and low humor in it. That comedy is certainly not missing here (putting me in mind of Samuel Beckett’s tragicomedies), but let’s just say Pegeen Mike’s lament for Christy at the end is not played for laughs.

“Ballet Shoes,” the holiday spectacular based on a 1936 novel by Noel Streatfeild, was adapted by Kendall Feaver and is the kind of sprawling show only the National Theatre can pull off, using all of their big Olivier stage (to Feb. 21). It has been brought back as part of the inaugural season of the National’s new artistic director and co-CEO, Indhu Rubasingham, who has come to the National from the Kiln Theatre. (And it is the kind of multicultural celebration of life that you’ll never see at the now Trumpian Kennedy Center.)

At its heart, this is the story of three unrelated orphan girls being brought up as sisters by an absent stepfather (Justin Salinger, who also ably covers multiple other roles, male and female) and his housekeeper (Lesley Nicol, who famously played the cook on “Downton Abbey” and shines here). The girls — played by Sienna Arid-Knight, Stephanie Eistob, and Scarlett Monahan — wear their hearts on their sleeves as they grow and mature in life and the arts.

This is a cast of 26 playing many more roles than that, but in a play directed by Katy Rudd, we never get lost but instead get caught up in the saga. Yes, it’s based on a children’s book, but there’s something to appeal to all ages. (At the performance I attended, The Queen seemed to be having a good time.)

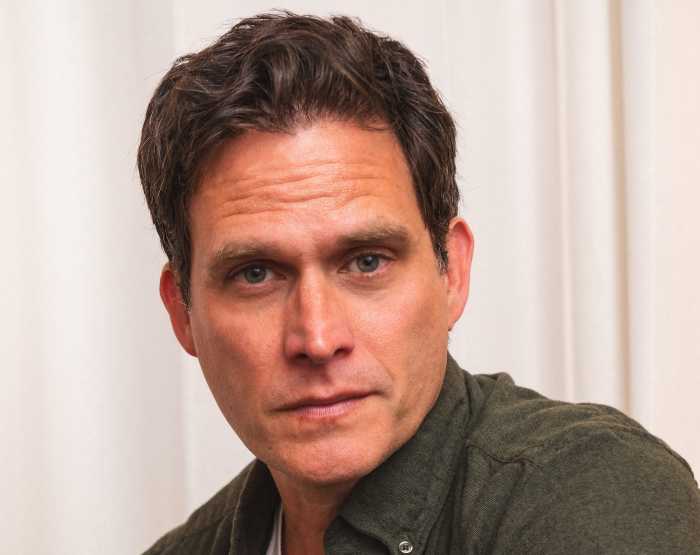

At the National’s Dorfman house (to Jan, 17), Clive Owen and Saskia Reeves are commanding the stage in “End,” by David Eldridge about Alfie, a prominent DJ, and his partner Julie, an accomplished novelist and teacher — both in their 50s. From the get-go in this two-hander, this is about DJ’s terminal cancer, how he wants to die, and whether Julie can let go of him. Conversations that are uncomfortable to have — and watch — ensue. How does their long-term love inform these discussions? There are no “right” answers about when to end treatment and how. Is it selfish of Alfie to want to withdraw and wind down? Is it loving for Julie to urge him to keep fighting against the odds? A thoughtful, timely play with two great actors.

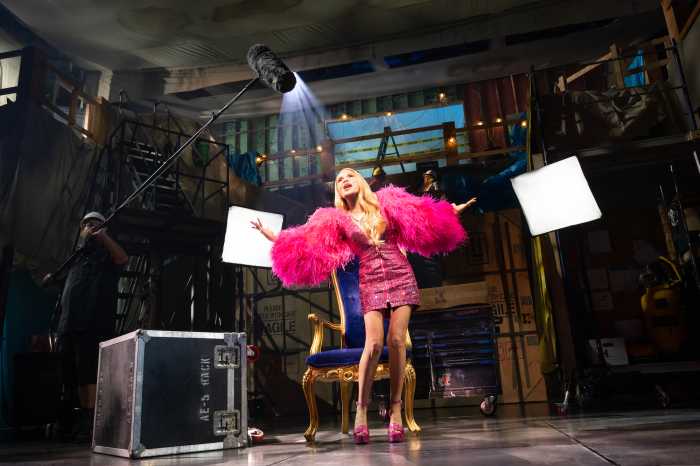

Cole Escola’s smash hit “Oh, Mary!” is on at the Trafalgar Theatre here (to April 26), where you can see it for a fraction of what you’d pay on Broadway. My gay friend in from Paris who’d never seen it loved it.

The new hit in the West End is an improbable musical of “Paddington” that has gotten raves at the Savoy Theatre and is booking through Feb. 14, 2027. Sarah Crompton of WhatsOnStage wrote “This is a show about welcoming foreigners, about asserting the values of kindness and tolerance that used to be Britain’s hallmarks.”

COMING UP

The late Tom Stoppard’s play “Arcadia,” directed by Carrie Cracknell, is at The Old Vic (Jan 24-Mar. 21).

Rosamund Pike is starring in the transfer of “Inter Alia” to Wyndham’s (Mar. 19-Jun. 20), a play I loved at the National this past summer. She balances her role as a leading judge and mother of a troubled son in Suzie Miller’s searing play.

“Please Please Me,” by Tom Wright about Brian Epstein, the gay man who discovered and managed The Beatles, is at the Kiln Theatre, April 16-May 23.

At the National Theatre, the gay playwright Terrence Rattigan’s 1963 “Man and Boy” is at the Dorfman (Jan. 30-Mar. 14) starring Ben Daniels and Laurie Kynaston as father and son. Maxim Gorky’s “Summerfolk” is at the Olivier (Mar. 6-Apr. 29). “Les Liaison Dangereuses” is being revived by Marianne Elliott at the Lyttleton (Mar, 21-Jun. 6) starring Lesley Manville.

And at the Theatre Royal Haymarket, legendary actors playing legendary actors: Ralph Fiennes is Sir Henry Irving and Miranda Richardson is Ellen Terry in David Hare’s new “About Grace Pervades” (Apr. 24-July 11).

Cynthia Erivo is Dracula from Feb. 4-May 30 at the Noël Coward Theatre.

MUSEUM EXHIBITIONS

There are two at the Tate Britain that are not to be missed. “Turner & Constable: Rivals & Originals,” about contemporary masters J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837), is on through April 12. They made landscapes a fit subject for art, no longer just the background for portraits and historic scenes. Their innovations in art are on full display until we get to the end of their lives and they are presaging Impressionism, which doesn’t formally arrive until the 1870s with Monet.

The “Lee Miller” photography exhibit at the Tate Britain (to Feb. 15) is a comprehensive survey of the work of Miller (1907-’77), who started out in Paris at 18 studying costume, lighting, and design, returning to New York in 1926 to become a high fashion model in New York. Miller was featured in Vogue magazine in shoots by all the top photographers, including Edward Steichen. In 1929 she returned to Paris, lobbying successfully to be a protege to Man Ray, and together they gave life to the technique of “solarisartion” and creating surreal photos. Moving to New York, Cairo, and back to Paris, she never stops innovating. In London, at the outbreak of World War II, she became a war photographer for Vogue across the European Theater on the front lines, ending up there for the liberation of concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau and capturing some of the most indelible images of the horrors there.

We owe much of this exhibit to Miller’s son, Antony Penrose, who discovered 60,000 of her photos and negatives after she died in the attic of their house in Sussex. (Kate Winslet produced and starred in “Lee,” a feature film based on Penrose’s book about his mother.) More info at tate.org.uk.

At the National Portrait Gallery until Jan. 11 is “Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World,” with an emphasis on the fashion photography of Beaton (1904-’80), but we get lots of glimpses into his gay world amidst the Bright Young Things post World War I, his celebrity and royal family photography, and on to his work as a war photographer in World War II. It is a sumptuous display of his photography capped by his design work for the stage and screen productions of “My Fair Lady,” winning two Oscars for the latter.