Incumbent Assemblymember Deborah Glick. | DEBORAHGLICK.COM

BY PAUL SCHINDLER | Asked to describe the significance of her nearly 26-year tenure in the State Assembly, out lesbian Democrat Deborah Glick talks about the legacy issues that would define a legislator’s career.

“I am clearly one of the foremost spokespeople for women’s reproductive rights,” she said in an interview this week.

The chair of the Assembly Committee on Higher Education, Glick, unsurprisingly, added, “I am a strong and effective advocate for public higher education in New York.”

Incumbent emphasizes long hauls to move the needle; challenger says the people need an organizer

Lest anyone assume that a legislator first elected in 1990 is now simply part of the establishment, however, Glick is quick to remind listeners of the historic role she played as the first out LGBT person elected to public office in New York State.

“The only lesbian in the legislature is too much of an insider?,” she asked rhetorically in response to criticism from her September 13 Democratic primary challenger in Lower Manhattan’s Assembly District 66. “Women are outsiders. I see myself as someone who has worked effectively despite being an outsider.”

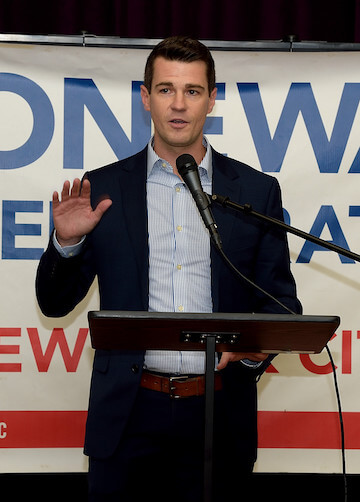

That primary challenger, Jim Fouratt, who is also gay, runs little risk of being branded as part of the establishment. In a career that has spanned Off Off Broadway, record producing, alternative radio and newspapers, and founding big name nightclubs, he built the résumé that backs up his claim to being a “cultural instigator.”

Fouratt has also been part of street activism in New York going back half a century — arrested in anti-Vietnam War protests, participating in the Stonewall Rebellion and joining the ranks of the Gay Liberation Front, marching with ACT UP, and most recently fighting to save St. Vincent’s Hospital and block a hydro-fracked natural gas pipeline from being built along Lower Manhattan’s far west side.

His recent activism informs his case against Glick. She was “silent,” Fouratt says, on St. Vincent’s closing in 2010; “silent” on the gas pipeline some environmentalists charge has created a “blast zone.” And, he asserts, “Glick’s stealth Hudson Park Trust air-rights giveaway” is enabling a major shift in the streetscape and skyline of the historically low-rise West Village.

Underlying these specifics, however, is Fouratt’s view of what role an elected official should play — that of community organizer-in-chief, keeping voters informed every step of the way in developing policy and mobilizing them to demand responsiveness from the centers of power.

The St. Vincent’s issue is a case in point. That its closing is still being discussed six years after the fact is indicative of the potency its demise had in the minds of Lower Manhattanites. Then-City Council Speaker Christine Quinn had her one-time frontrunner status in the 2013 mayoral contest tarnished and then destroyed due in no small measure to charges that she too had been “silent.” That, despite the fact that many healthcare experts chided the hospital itself for its chronic mismanagement and said its departure was a sign of the times in that sector.

Responding to suggestions that it would be possible to bring a full service hospital back into the West Village, Glick told The Villager, Gay City News’ sister publication, “I do feel that people who think that a full-scale hospital is coming back aren’t facing the reality of healthcare.”

In turn, Fouratt’s indictment of Glick on St. Vincent has less to do with that hospital’s financial management and the economics of healthcare in today’s economy and more with political style.

“Why didn’t she try to intervene?,” he said. “She had the power to rally people.”

In response to Glick’s statement that her hands were tied on the siting of the gas pipeline in the West Village because it was a federal government decision, Fouratt said, “She should have been informing the public.”

That kind of rallying is a legislator’s job, Fouratt asserted, and he pointed to several Manhattan colleagues of Glick’s — Brian Kavanagh and Linda Rosenthal — as examples of that style of leadership and community engagement. Neither Democrat has returned the compliment, though.

Challenger Jim Fouratt. | FACEBOOK.COM/JIMFOURATT

Fouratt is clearly sensitive to charges that in rallying crowds, in being an “instigator,” he runs the risk of being simply a gadfly. He was stung by criticism reported in The Villager from Allen Roskoff — president of the LGBT-focused Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club and himself a maverick unafraid to make noise (and like Fouratt, an erstwhile Bernie Sanders supporter) — who was scornfully dismissive of Fouratt’s chances with “anyone of any credibility.”

Fouratt insisted he is not running to be another Charles Barron, a fiery African-American assemblymember from Brooklyn who earned a reputation as a disrupter from his days on the City Council — though Fouratt was also quick to voice respect for the role Barron plays in politics.

Anyone who doubts Fouratt’s ability to work to forge solutions out of difficult circumstances, he said, should learn about the role he played in helping push then-Mayor Ed Koch from his intransigent position that he would never sell an old schoolhouse on West 13th Street to LGBT advocates hoping to build a community center.

The other daunting challenge facing Fouratt is his decision to take on an historic figure in the LGBT community.

“It is very hard to run against someone who has served so long and someone who made history,” he conceded. “I credit her work on women’s health issues, but you don’t stand up for a hospital? Really?”

When Glick first arrived on the scene, Fouratt said, “I thought identity politics worked, all other things being equal. In 2016, it becomes very different. There has to be very different criteria.”

In his reading of her career, Glick changed fundamentally after her 1997 borough president race, when the party establishment went with C. Virginia Fields instead. Since then, in his accounting, she’s been a loyalist, which explains her staunch support for disgraced Assembly Speaker Shelly Silver to the bitter end. If she was silent about St. Vincent’s, Fouratt charged, it was because Silver decided Democrats weren’t going to stand in the way of Rudin Management’s redevelopment of the hospital into luxury condos.

There is no doubt that Glick was an ally of the speaker, and the toughest criticism on that score is her continued support for Silver after secret settlements he authorized for women who lodged sexual harassment claims against Brooklyn Assemblymember Vito Lopez came to light in 2012 — almost three years before Silver’s own legal troubles emerged. Looking back on that, Glick said she was uncertain as to whether Silver was acting on advice of counsel but that the Democratic conference demanded and received a public apology from the speaker for those payments. Reforms have since been made in Assembly handling of such complaints, and with Glick now overseeing the intern program there, she said there have been no problems.

Fouratt’s central charge against her — that she is too ingrained with Albany’s leadership structure — is something Glick said her “colleagues are quite surprised to hear.”

In terms of transparency, she noted that Fouratt is only on the ballot because he was chosen to replace Democratic district leader Arthur Schwartz, who collected the signatures needed to run and then begged off for health reasons. Glick described the switch as a “backroom deal.” In declining Fouratt’s challenge to a debate, she said he has “never demonstrated any public support” and then alluded to the gadfly rap on her opponent, saying, “This is a people business, and you have to get along with people. Do I think Jim has had measurable support in any group he’s belonged to? No.”

Glick and Fouratt may disagree on the ethics of her longstanding relationship with Silver, but there can be little doubt but that she is a fierce defender of the Assembly as an institution — and of its Democratic majority. She regularly denounces the obstructionism that the Senate Republican leadership throws in the way of progressive advances and of issues important to New York City.

But if she is rarely critical of Assembly Democrats, the same is not necessarily true of Democratic governors. In discussing her mission as chair of the Higher Education Committee to preserve “access” to the state’s two public college systems — CUNY and SUNY — Glick lamented, “Not that we have a receptive executive, but I can’t think of when we did, except for a short time with [Governor Eliot] Spitzer before all the noise began.” With New York State having reaped nearly $7 billion in legal settlements last year, Glick had pushed to set aside $1 billion — half for SUNY, half for CUNY — to buffer the systems’ endowments. Governor Andrew Cuomo showed no interest, and instead she spent the last session “fighting rearguard actions.”

For a governor who is fighting to increase the state minimum wage, she noted, support for CUNYwould benefit the very same families, who have been faced with significant increases in public college tuition in recent years, clouding the economic future for their children.

On women’s health, Glick is also often fighting off efforts to turn the clock back. Fourteen years ago, after a five-year fight, she was successful in ensuring that state insurance regulations required any employee drug reimbursement program to cover contraceptives — an issue she now sees headed south on the national stage in the wake of the Supreme Court’s controversial 2014 Hobby Lobby decision.

“I’m afraid I will have to fight that for the rest of my natural life,” she said.

A women’s health and wellness law now mandates that insurance cover the cost of mammograms for women 40 and over, reducing what had in many plans been a minimum age of 50. But Glick’s efforts to codify Roe v. Wade in state law — essentially bringing New York’s abortion rights statute enacted in 1970 up to the standards of the 1973 Supreme Court decision — continue to founder on staunch opposition in the GOP Senate.

And every session, Glick said, she fights proposed women’s health reversals one would expect to see in the Texas legislature, including repeated efforts to ban Medicaid reimbursement for abortion services.

Glick shares the view of many of her Democratic colleagues on a key issue of concern in the LGBT community — that despite Cuomo’s executive directive last year that resulted in regulations interpreting sex discrimination provisions of state law to ban discrimination based on gender identity and expression, the legislature should pass the long-stalled Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act.

“As a legislator, I am never comfortable with executive orders alone,” she said. “Whether it’s fracking or GENDA or sexual orientation conversion efforts, you need to codify all these things. It could always be overturned by a new governor.”

On that, she is in agreement with Fouratt, who said, “Personally, I think the legal protections are in place, but I have been persuaded by people who are closest to the issue that this law is needed.”

Years ago, Fouratt, who has always described himself as gender-nonconforming, got himself into some amount of trouble with the transgender community over doubts he expressed about whether gender transition was always the right course. Saying that he now sometimes helps transgender people access services at the LGBT Community Center’s Gender Identity Project, Fouratt admitted he has “tempered my statements.” But being the iconoclast he is, he also speaks his mind, saying, “I am very worried about the survival of femme boys and butch girls.”