The Metropolitan Opera commissioned composer Nico Muhly for an operatic adaptation of Winston Graham’s 1961 psychological thriller “Marnie,” which was the basis for the 1964 Alfred Hitchcock film starring Tippi Hedren and a virile Sean Connery. Though it has critical defenders, the film is considered one of the master’s late career misfires. The opera with a libretto by Nicholas Wright had its world premiere last year at the English National Opera and arrived for its US premiere at the Met on October 19. (Hedren made a special appearance at the final curtain call opening night.)

Graham’s heroine is a troubling enigma who moves from job to job and town to town, changing her identity and disappearing after she has robbed her employers. Emotionally disconnected and sexually frigid, Marnie lives on the periphery of society, avoiding personal relationships. She meets her match in the widowed businessman Mark Rutland, whom she attempts to steal from and who in turn blackmails her into marriage. His pursuit of her forces Marnie to face her demons, which include a long-buried childhood secret.

Hitchcock’s script made many changes including changing the locale from England to Baltimore and making Marnie’s childhood trauma more sexual in nature to explain her aversion to men. Wright’s libretto faithfully follows Graham’s original novel. Graham’s “Marnie” and his “Poldark” novels both include a scene where the “hero” rapes a female protagonist. In “Marnie,” Mark attempts to rape Marnie when she physically rejects him on their wedding night. In “Poldark,” Ross rapes Elizabeth when he discovers she plans to marry his archenemy Warleggan. Last year, there was considerable hue and cry of “rape fantasy” when this scene aired in the BBC’s latest “Poldark” miniseries. It is also problematic in “Marnie” (both the film and the opera) since both our hero and heroine commit actions that alienate our sympathies. Wright makes other characters openly scold Mark for his manipulation and abuse of his wife but it remains distasteful.

Wright’s libretto is full of short, matter-of-fact phrases, blatant plot exposition, and prosaic language that limit lyrical expansion or extended musical concepts. In the program notes, Muhly explains how his compositional process was “inspired” (and limited) by Wright’s libretto: “Nick then went off and started sending me individual bits of the first draft of a libretto, and I realized that we had these wonderful opportunities for moments that aren’t quite arias that we decided to call ‘links.’ The premise was that Marnie doesn’t necessarily have stand-alone arias but instead these transitional musical moments where she concludes one scene with one thought and begins the next scene with another. These links function like arias would in a more traditional operatic structure…”

As a result, all we ever hear are short arioso-like solos and conversational speech-song “links” that are all on the same musical level and devoid of melodic development. They don’t “link” us to the inner lives of the characters.

Muhly’s music all sounds the same — meandering, restless, and busy in bleak minor keys. There are interesting orchestral textures that suggest Britten and Janácek with a sprinkling of Philip Glass and Stravinsky. Like Emilia Marty in Janácek’s “The Makropulos Affair,”, Marnie is a shape shifter who always keeps the initials “MH” just as Elina Makropoulos keeps the initials “EM” in her various incarnations.

The score functions like a movie soundtrack in providing a general atmosphere and punctuating a dramatic action or utterance, but it does not provide a voice for the characters. Muhly’s music fails to adapt in color or rhythm even when the emotions of the drama drastically change. The fox hunting scene where Marnie is forced to shoot her beloved horse Forio is a case in point: the music fails to create tension or pathos as needed. The choral writing is masterful and the orchestration is accomplished. But you don’t care because the monochromatic music doesn’t create characters or drama. Ultimately, it is boring.

The Met has lavished this misfire with a top-notch physical production and design. The kaleidoscopic sets in film noir monochrome with projections designed by Julian Crouch and 59 Productions are contrasted with colorful, eye-catching period-specific costumes by Arianne Phillips. However, Michael Mayer’s direction is less focused, overusing onstage doppelgängers who mainly move props.

When Marnie and Mark face each other alone in a cruise ship cabin on their wedding night, the moment is vitiated by a background panoramic projection of a ship at sea and the conjugal bed filled with male supers in suits and fedoras. Here we need to see these two tortured souls trapped alone together in intimate contact. As staged here, all sexual and dramatic tension was lost. In fact, sexual repression, frustrated desire, and tender romantic feelings are all absent from the characters and music, rendering the central relationship in the story pointless and empty. Why do they stay together and why should they (or we) care? Whatever suspense or dramatic conflict the first act creates is dissipated by the second act.

The cast is fantastic from top to bottom. In the title role, Isabel Leonard is fantastic and would be a perfect Marnie if one existed in the music. Her multifaceted mezzo-soprano has tones that suggest lyric soprano fragility, cool seduction, and dark anguish. Her mask-like beauty both entices and tells us to keep our distance — we can never see what is underneath. Muhly’s use of a mini-chorus of Marnie alter egos evoking her splintered identity is an intriguing concept but is used too inconsistently musically and dramatically to register.

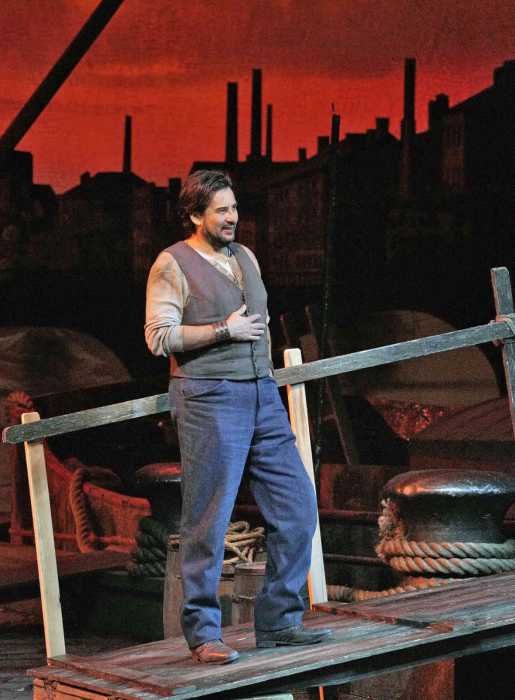

Mark’s mother tells us that his first wife told her she didn’t know who he was and she doesn’t know who he is either. Christopher Maltman as Mark remains an opaque cipher because that is what the role demands. Maltman lacks the magnetic charisma of a young Sean Connery that might make us understand why Marnie can’t run away from him.

Vivid cameos by Janis Kelly as Mark’s icy mother, countertenor Iestyn Davies as Mark’s creepy brother Terry, Denyce Graves as Marnie’s malefic mother, and Anthony Dean Griffey as the repellant hypocrite Mr. Strutt embody the hostile social forces that force Marnie to live in a perpetual state of flight and deception.

The Met Orchestra led by debutant maestro Robert Spano found all the colors in Muhly’s heavy orchestration. The Met Chorus led by Donald Palumbo distinguished themselves in the best vocal writing Muhly composed for the opera. But all it was all sound and fury signifying nothing.