The organization that produces New York City’s annual Pride Parade and related events said that its contracts with parade sponsors allow those companies to purchase a place in the parade, but do not guarantee that their contingents would be included in the three-hour live broadcast of the parade on local broadcast TV.

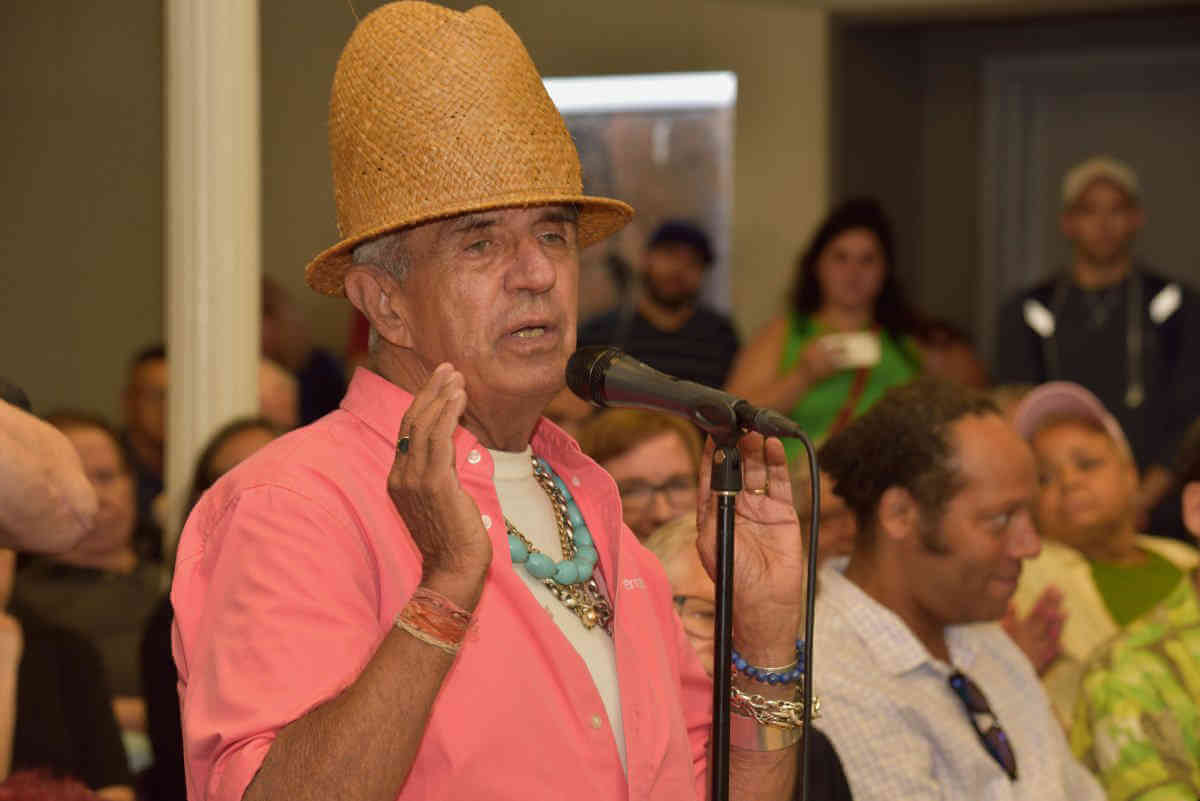

“I can tell you that there are some multiple-year agreements that include float participation or vehicle participation,” said Maryanne Roberto Fine, a co-chair of Heritage of Pride (HOP), during an August 13 town meeting held at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center. “There have been contracts that will give a range, but nothing that would specifically say you will be on the broadcast… There are contractual obligations to placement.”

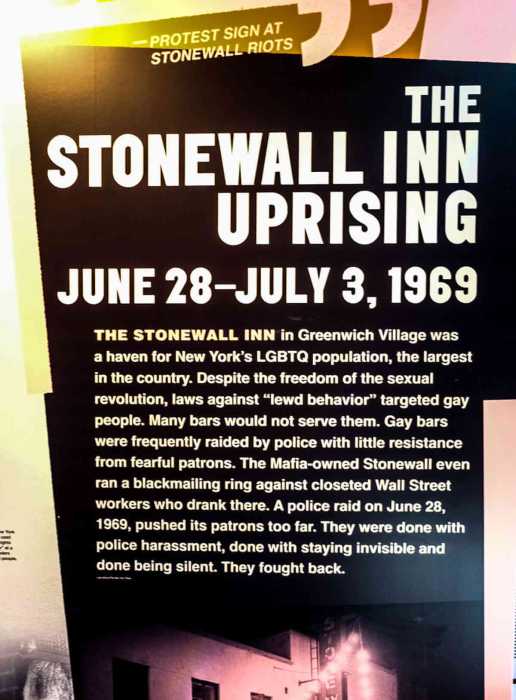

While community groups and non-profits comprise most of the contingents in the Pride Parade, which commemorates the 1969 Stonewall riots that mark the start of the modern LGBTQ rights movement, for-profit companies dominate the event because they use large floats and can field more marchers. Complaints about those companies are longstanding, but in 2017 and particularly in 2018 activists with deep roots in the LGBTQ and other movements began to more aggressively press HOP to limit the corporate presence in the march among other demands.

While activists have long suspected that sponsors can purchase a spot in the parade, inevitably toward the front, this was the first confirmation of that from HOP. It offends activists because the companies are effectively buying a status that they never worked for and have not earned. That the companies are privileged misrepresents the broader community, activists said.

“The issues that our community is working on are not being represented in the best way in this march,” said Cathy Marino-Thomas, a longtime LGBTQ activist, at the town hall. “We have a media opportunity for three hours every year now, thank you very much, but nothing that this community is working on is represented in those three hours.”

While some in the community see the corporate floats as evidence of the community’s success and improved status in the US, Eugene Fedorko, who was in the 1970 and 1971 marches, objected to the current nature of the parade and how it misrepresents of the community’s history.

“I cannot believe the focus of the parade has been taken from the heroism of the early activists and their political points,” he said. “Corporations were nowhere to be found in 1970 and ‘71… Now they are acting as though they threw the first brick on Christopher Street in 1969… It’s a huge insult to the early activists and the current activists.”

In 2018, activists organized as the Reclaim Pride Coalition and, like 2017, demanded a resistance contingent in the parade, which they won. They opposed the required use of wristbands to identify marchers, a practice first employed this year that will not be repeated in 2019. They objected to the new route, which began in Chelsea, headed south on Seventh Avenue, east on Christopher and Eighth Streets, and then north on Fifth Avenue to end at 29th Street. It is unknown if that route will be used in 2019, which will mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

Chelsea residents were unhappy with the parade being staged in their neighborhood.

“This has to be done differently next year,” Paul Groncki, the chair of the 100 W. 16th St. Block Association, said at the town hall. “The impact on Chelsea residents was immense. I had complaints from almost every block in the neighborhood.”

The new route was supposed to shorten the parade’s run time. In 2017, the parade, which always begins at noon, ended at 9:38 p.m. This year it ended at 9:14 p.m. The parades in 2016 and 2015 were each about eight hours long. In 2010, the NYPD, which issues parade permits, issued an edict requiring that all parades last no more than five hours. The Pride Parade, which is among the four largest public events in the city, has not been close to five hours long in years.

While activists this year were initially focused on demands related to the 2018 parade, they were aware early on that they would also need to tackle 2019, given the significance of the Stonewall anniversary. A concern at the town hall was that HOP may have already signed agreements that require HOP to put sponsors at the front of the parade.

“Stop selling places in the parade,” Emmaia Gelman said. “That’s disgusting.”