In 1945, when I was six years old, I brought two bouquets of flowers to school, one for my first-grade teacher, Miss Dickerson, the other for my desk. It was an old-fashioned desk in a two-room country school house and contained an ink-well. I inserted the paper cup containing the flowers in the inkwell and thought it was a lovely addition to our classroom. I had gathered the flowers from our backyard garden and was sure they would be a hit with my teacher and my classmates.

They were not.

Minutes after installing my floral arrangement, I was greeted by hoots of “Pretty Flowers!,” and that remained my name until I left the school three years later.

Miss Dickerson seemed confounded by both my gift and the derisive nickname bestowed on me by my fellow students. Her apparent confusion at the sight of a boy clutching a bouquet seemed a signal to the class to up the ante; their taunts turned to insults. During recess I was pounded to the ground and later sent home with a bloody nose.

By the time I was a 14-year-old freshman in high school, I had earned another nickname — Margaret Rose. This rather descriptive moniker — I had developed into an effeminate adolescent — was not shouted out by schoolyard bullies. It was handed to me by my father, who being the family jokester thought that he could tease me out of my unconventional behavior through what he deemed comedy. While I laughed outwardly at his funny label for me — in the family, we all agreed that being named after the queen of England's younger sister was a real hoot — inside, I felt great shame and sadness. My photo peering from the pages of the school yearbook in 1954 was a study in melancholic desperation. Many of my fellow students refused to sign my yearbook, saying I was a sissy; even worse, others wrote scathing comments addressed to Girlie Boy and Miss Oglesby. After tearing my photo out of the freshman class pages, I shredded and burned the yearbook.

Midway through high school, I engineered a radical self-transformation, morphing into a swaggering gym rat who pumped iron every day and had the biggest biceps in school. Suddenly, nobody bothered or belittled me anymore. Some girls even started flirting with me. By senior year, Slam Books — the 1950s notebook version of today's Facebook — that circulated in the cafeteria and the gym listed me as one of the coolest, most popular kids in school.

My game of deception had succeeded brilliantly. I had gone “underground” and nobody but me knew what really lurked inside. My father seemed pleased that his Margaret Rose tactic had worked. One day, he buddied up to me, telling me I was nearly a man now. In recognition of my impending adulthood, he reached into his shirt pocket and pulled out a pack of cigarettes, offering me a Camel.

Years passed and my sadness turned to toughness. Smugly satisfied, I had learned to play by straight society's rules. I was outstanding in college and later excelled in the professional world. Happiness came to me slowly as I built my own tiny sphere of optimism and fun with a small human network of loving support that eventually included a domestic partner. We have been a loving pair for 30 years.

When President Barack Obama recently announced his support for gay marriage, I smiled and thought to myself how different my life might have been if President Harry Truman had done the same thing in 1945.

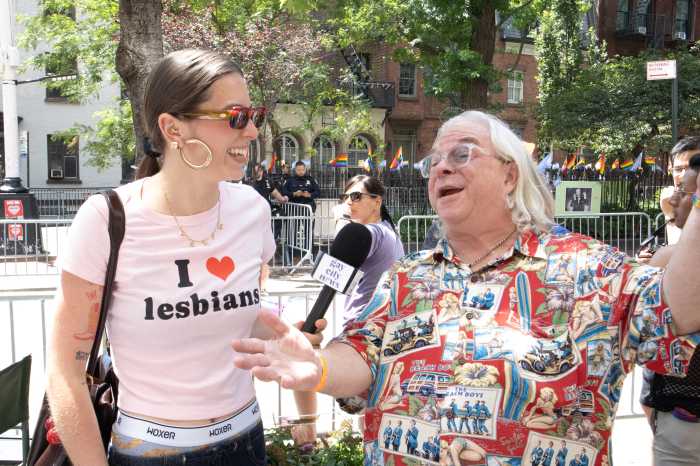

Sam Oglesby, a New York-based writer of memoirs, whose latest publication is “RAJAS BOOK — Twelve Months in a Life,” can be reached at ogl39@aol.com.