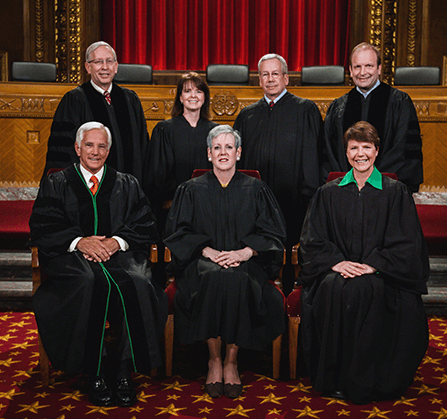

The Ohio Supreme Court, with Justice R. Patrick DeWine at right in the back and Justice Terrence O'Donnell in the front left. | OHIO SUPREME COURT

The seven-member Ohio Supreme Court unanimously rejected a free speech and equal protection challenge to the state’s law making it a felony assault for a person who knows he is HIV-positive to engage in “sexual conduct” with another person without disclosing their HIV-positive status.

The court divided 4-3, however, on the appropriate legal analysis for reaching its October 26 decision. Upholding an eight-year prison sentence for Orlando Batista, four members of the court ruled that the law regulated conduct rather than speech and the state has a rational basis for imposing the criminal disclosure requirement on people living with HIV when they have sex — but not for engaging in other types of conduct that could transmit HIV and not on those living with other comparable sexually-transmitted diseases, such as hepatitis C.

Batista learned that he was HIV-positive while serving a prison sentence, though he was apparently infected before being incarcerated. After his release, he had sex with his girlfriend without disclosing his diagnosis. The opinion for the majority by Justice Terrence O’Donnell does not indicate whether Batista’s girlfriend became or was already infected or whether Batista’s medical treatment had suppressed the virus to undetectable levels, which would make sexual transmission very unlikely.

State Supreme Court unanimously rejects free speech, equal protection challenge

Batista argued that the Ohio law unconstitutionally forced people living with HIV to disclose their status, a form of government-compelled speech. He also argued that singling out people living with HIV for this disclosure obligation in connection with sexual activity raised equal protection concerns because people with other similar infectious conditions were not burdened with this obligation and no such obligation was placed on people engaging in non-sexual activities that could transmit HIV.

In his majority opinion, Justice O’Donnell wrote, “The First Amendment does not prevent statutes regulating conduct from imposing incidental burdens on speech.” In this case, he argued, the statute was aimed directly at conduct: engaging in sex without having disclosed one’s HIV-positive status to a partner. O’Donnell pointed to support from appellate courts in Missouri and Illinois, quoting a 2016 Missouri decision stating, “While individuals may have to disclose their HIV status if they choose to engage in activities covered by the statute, any speech compelled by it is incidental to its regulation of the targeted conduct and does not constitute a freedom of speech violation.” The Illinois Supreme Court was even more direct, stating that state’s law did not have “the slightest connection with free speech.”

Three members of the court disagreed with this approach to the analysis, in a concurring opinion by Justice R. Patrick DeWine, who wrote, “When the government tells someone what he must say, it is regulating speech.” But, he added, Batista did not have a valid free speech claim because the state met the necessary strict scrutiny test to justify a content-based regulation of speech.

“Under strict scrutiny,” wrote DeWine, “a content-based regulation of speech will be upheld only if it is narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling governmental interest and it is the least restrictive means of doing so.”

The government interests, he found, were preventing the spread of HIV and “ensuring informed consent to sexual relations,” noting that society has “long criminalized nonconsensual sexual relations.” These two together, DeWine wrote, “rise to the level of a compelling government interest.”

The Illinois ruling O’Donnell pointed to came from 1994, and DeWine acknowledged expert testimony Batista presented that advances in treatment for HIV infection since then had led to normal lifespans for those infected, rendering HIV infection no longer an “invariably fatal” disease. The issue today, he asserted, isn’t whether the consequences of being infected are less serious now than they were years ago. Rather, he wrote, “the question is who gets to evaluate that risk: should the HIV-positive individual get to assess that risk for his sexual partner or should the partner get to make her own decision. Fair to say that most — if not all — people would insist on the right to make that decision for themselves.”

DeWine also concluded that the obligation imposed by the law was “narrowly tailored” to advance the government interest, by restricting the disclosure requirement to those who wish to have sex and requiring disclosure only to a sexual partner.

“I cannot fathom — and Batista has not advanced — any less restrictive or more narrowly tailored means that could have been employed by the government to achieve its interests here,” he wrote.

Regarding Batista’s equal protection challenge, Justice O’Donnell wrote for the court majority that the comparison to hepatitis C “is misplaced” since the decision of which public health issues to address is a legislative, not a judicial function. He rejected the idea of having the court “weigh the wisdom of the legislature’s policy choices,” claiming that this “beyond our authority.”

In an equal protection case, unless there is a suspect classification — like race or sex — or a fundamental right involved, all the state needs is a rational basis for its actions. Since the court majority found no First Amendment free speech issue and knowingly being HIV-positive is not a “suspect classification,” the court’s analysis is no more demanding than to ask whether the legislature had any conceivable basis for singling out HIV-positive people for this disclosure requirement. O’Donnell found that the lack of similar treatment for those knowingly infected with hepatitis C “does not eliminate the rational relationship between the classification here — individuals with knowledge of their HIV-positive status who fail to disclose that status to sexual partners — and the goal of curbing HIV transmission.”

O’Donnell made the same argument regarding Batista’s claim the state was irrational in imposing the disclosure obligation regarding sexual conduct but not in connection with other modes of HIV transmission.

In his acknowledgement of treatment advances and the reductions in the risk of transmission, O’Donnell wrote, “We cannot say that there is no plausible policy reason for the classification or that the relationship between the classification and the policy goal renders it arbitrary or irrational.”

Reading these opinions is frustrating for those who have kept up with the latest findings of public health authorities on the efficacy of state-of-the-art HIV treatments to reduce the risk of sexual transmission to a negligible level, but evidently the court was unwilling to entertain seriously the proposition that the state does not have a legitimate interest in imposing the disclosure requirement across the board on HIV-positive people, including those who do not pose a real risk of transmission. It seems very likely the court simply does not fully understand the scientific issues involved.

Batista was represented by attorneys from the Hamilton County Public Defenders Office, but also had exceptional support from amicus briefs by the American Civil Liberties Union of Ohio, the Center for Constitutional Rights, the State Public Defenders Office, and half a dozen HIV, LGBTQ, and other civil rights and criminal defense advocates, including the Treatment Action Group, GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders (GLAD), the National Center for Lesbian Rights, and the Human Rights Campaign.

Batista could seek US Supreme Court review on the federal constitutional claims he made, but that court rarely agrees to review decisions that could be premised on independent state constitutional grounds. On the other hand, an argument could be made that federal constitutional protection for speech and equality is more protective of individual rights than the relevant state guarantees.