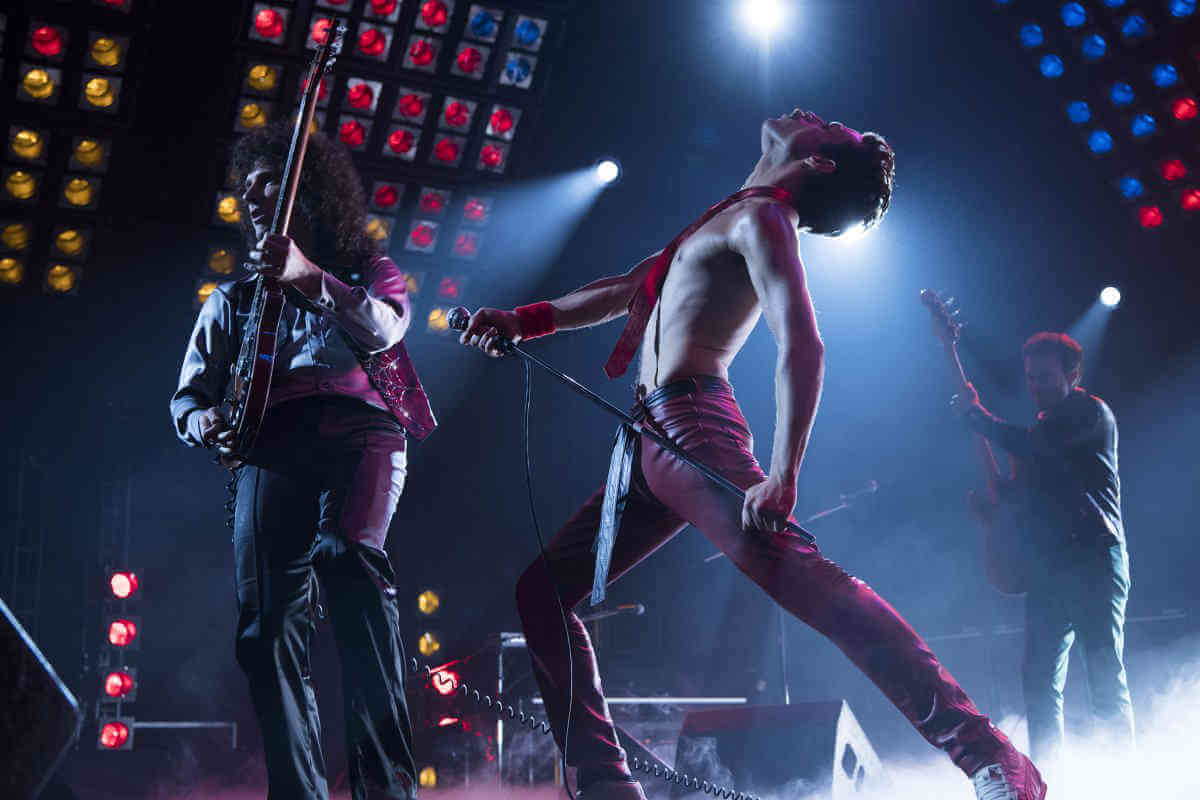

The official credits of the Freddie Mercury biopic “Bohemian Rhapsody” are deceptive. Due to Director’s Guild of America regulations that only one director can be credited, Bryan Singer receives that billing. However, he stopped showing up to its set three months into its shoot, was fired by 20th Century Fox, and replaced by British director Dexter Fletcher. While Fletcher completed the film, it’s anyone’s guess who shot exactly what footage in the version of “Bohemian Rhapsody” now in release. If the film has a consistent look, it may be due to the assistant director or editor rather than either Singer or Fletcher. Key emotional scenes between Mercury (Rami Malek) and his lovers and managers are consistently shot in near-darkness with spare, stylized lighting throughout.

Still, “Bohemian Rhapsody” feels inadvertently elliptical. At 135 minutes, it didn’t need to be any longer — its pacing probably would have suffered. But the film would have benefited from devoting more than five minutes of screen time to Jim Hutton (Aaron McCusker), whom it presents as Mercury’s savior from a life of drugged-out decadence (depicted in a PG-13 manner) and bad decisions. The script shortchanges every character except Mercury, making them play second fiddle to his needs and desires. Even if it sometimes makes him look like a jerk, it never lets us forget that his star shone brighter than everyone around him (including the surviving members of Queen, who came up with the idea to produce this film in 2010).

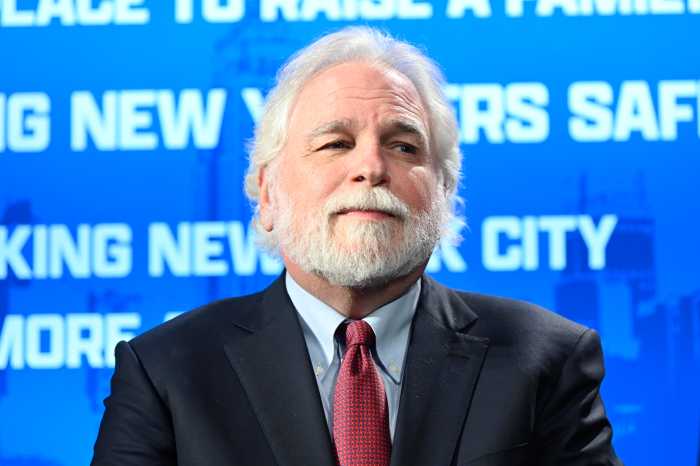

“Bohemian Rhapsody” follows “Love, Simon” as this year’s second full-fledged studio release about an LGBTQ protagonist. Singer is openly bisexual, but he’s repeatedly been accused of raping teenage boys (with a civil suit filed last December). Those stories go back more than a decade, and as a result I doubt anyone sees his direction and production of the “X-Men” series sending an allegory about the LGBTQ civil rights struggle into multiplexes as a source of pride for our community.

But “Bohemian Rhapsody” was made by more than one person, and the work of Malek, Fletcher, and Queen themselves should not become collateral damage from Singer’s behavior. Whatever the influence, the film has an odd time figuring out how to depict Mercury’s queerness. It can’t decide if he was really bi (as he tells his girlfriend Mary, played by Lucy Boynton) or gay (as she responds to him after that revelation, feeling used as a beard). That question has extended to much of the posthumous writing about the singer.

Mercury’s closet door now seems wide open during his lifetime, from Queen’s very name to the Castro Street clone image of his most famous period (which one Queen member likens to a Village People member at a 1980 party) to the lyrics of songs like “Killer Queen” and “The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke.”

Early scenes of “Bohemian Rhapsody” show Mercury happily living in what amounts to a polyamorous relationship with Mary and his manager Paul (Allen Leech) — even if that’s not what he calls it and the sexual aspects of his life with Paul go unstated — cruising a man at a gas station bathroom while on tour in America, casually calling himself a “queen” in conversation with other Queen members, and chatting on air with a DJ who is even campier than he is. He makes remarks about being outrageous and a misfit, which only make sense given his ambiguous sexuality. “Bohemian Rhapsody” also emphasizes that he came from an Indian background even if most Queen fans mistakenly thought Mercury was white.

Things only go downhill after he puts a name to his sexuality. The film has trouble envisioning early ‘80s gay life as anything other than a doomed path to contracting HIV. The scene that cross-cuts Mercury’s trip to a leather bar with the recording of “Another One Bites the Dust” (a rather pointed choice of a Queen song) could have come from William Friedkin’s “Cruising.”

Then the film seems to recognize its missteps, introducing Jim as his final lover and a positive gay influence on his life. Still, it never takes the effort to make Jim feel like a real person (although he was, his photo appearing during the end credits) rather than a narrative device.

“Bohemian Rhapsody” gives Mercury the happy ending he didn’t get in life by closing with Queen’s performance at Live Aid in 1985, six years before his death. Part of the reason this film took eight years to produce is that Sacha Baron Cohen, the original choice to play Mercury, dropped out because the band conflicted with him over the relatively light and sunny direction they wanted it to take. Closing “Bohemian Rhapsody” with an exhilarating 10 minutes of Queen hits performed at Live Aid (convincingly re-enacted by Malek) counters the common tendency to depict queer lives tragically, even if the decision to have Paul, Mary, and Jim stand together backstage happily watching the show is a step too far into corniness.

For once in a celebrity biopic, this ending puts the focus on music, something the film tries less successfully to do throughout by depicting the writing and recording of “Bohemian Rhapsody” itself as well as “We Will Rock You.” The film is a decidedly mixed bag, feeling thoroughly confused, but ultimately it manages to honor Mercury’s talent.

BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY | Directed by Bryan Singer and an uncredited Dexter Fletcher | 20th Century Fox | Opens Nov. 2 citywide