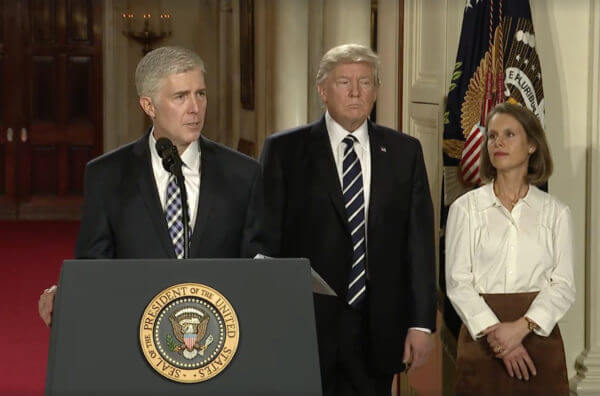

Judge Neil Gorsuch in the White House East Room on January 31 as President Donald Trump and Gorsuch's wife, Louise, look on. | WHITEHOUSE.GOV

BY ARTHUR S. LEONARD | When Justice Antonin Scalia died last February, then-candidate Donald Trump said that if he were elected he would appoint somebody in the mold of Scalia to take his place. That statement came in the context of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s statement that his Republican majority would not consider, much less confirm, anyone nominated by President Barack Obama to fill that seat. As far as the GOP was concerned, Obama had gotten his two seats on the high court, with the appointments of Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, and was entitled to no more. They wanted to preserve the chance to keep the Scalia seat as their own should their party’s candidate prevail in November.

In fact, in recent decades, two seats are what presidents have gotten –– George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George H.W. Bush. Ronald Reagan got to appoint four (though it took six tries to fill those seats, with two nominations foundering), but Reagan came to office following Jimmy Carter, who had no opportunity to name a justice –– so it’s not surprising there were more openings to fill. The four Democratic appointees on the current eight-member court were nominated two each by Clinton and Obama, and the four Republican appointees were nominated by Reagan and the two Bushes. At his death, Scalia was the senior member in terms of years of service, having taken the bench in 1985.

The initial reaction to the Gorsuch nomination by some Supreme Court observers was that it essentially restores the ideological balance that existed prior to Scalia’s death. Many cases each term are decided by unanimous or near-unanimous votes, but ideological balance comes into play on issues where there is a sharp divide between progressives and liberals, generally Democrats, and conservatives, usually Republicans. In recent years, those cases have been decided 5-4 or 6-3, and since Scalia’s death the court has deadlocked 4-4 on some significant cases, resulting in lower court decisions staying in place but with no new national precedent established.

Nominee’s tight embrace of Free Exercise Clause poses risk for LGBTQ anti-discrimination gains

Had the Senate given Obama’s pick, Court of Appeals Judge Merrick Garland, its typical consideration, the opening left by Scalia’s death could have been of monumental significance. A Garland confirmation would have reduced the deeply conservative contingent of the court to three members, as against a Democratic majority plus Anthony Kennedy, a Reagan appointee who sits at the ideological center of the justices, tipping the balance one way or the other on a case by case basis.

Although Garland’s record on the DC Circuit suggests a centrist judge without strong ideological leanings, that would place him somewhere between Kennedy and the incumbent Democratic appointees on the ideological scale. Most significantly, Garland’s confirmation would have given the Supreme Court a Democratic majority for the first time since the Lyndon Johnson administration.

A group of academics from the University of California at Berkeley –– Professors Lee Epstein, Andrew D. Martin, and Kevin Quinn –– released a study in December analyzing how the court’s ideological disposition would be affected by the appointment of any of the candidates Trump had previously announced as being in the running, a list based on suggestions he received from conservative think tanks. They concluded that most of the sitting judges on that list, based on close scrutiny of their records, would have voting patterns similar to Scalia and Samuel Alito, who was appointed by George W. Bush to the seat vacated by Sandra Day O’Connor, and whose appointment was then seen to have moved the Court rightward. They placed Alito and Scalia close together on the ideological scale, with Scalia slightly more conservative than Alito.

The Berkeley group rated Gorsuch as among the more conservative judges on Trump’s list, and situated him on the ideological voting scale between Scalia and Clarence Thomas, but somewhat closer to Scalia. Thus, on balance, Gorsuch’s addition to the court would move it to a more conservative disposition than it had before Scalia died, but probably without affecting how cases would have been decided had Gorsuch been sitting in Scalia’s chair during recent court terms.

Based on his writings on and off the bench, it is clear that Gorsuch is a committed “originalist” more in the mold of Thomas than of Scalia, who in recent years had taken to describing himself as a “faint-hearted originalist” because of his gradual acceptance of some constitutional interpretations that depart from what America’s founding generation might have embraced. Thomas, as shown in his dissenting opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 marriage equality case, clings to archaic constructions of constitutional language –– such as the use of “liberty” in the Due Process Clause –– because they are the meanings that American and English lawyers would have attached to the term in 1791 when the Bill of Rights was adopted.

Gorsuch has not written any opinions on LGBT issues for the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, where he has sat since 2006, though he has joined two unpublished opinions written by other judges in cases filed by transgender plaintiffs.

In one, Druley v. Patton (2015), an Oklahoma state prisoner was incarcerated in 1986, by which time she had already gone through gender transition, but she has been housed in a men’s prison. She complained there had been frequent interruptions in hormone treatments and the adequacy of the dosages provided by the prison, and that her request to be allowed to wear feminine underwear had been denied. The case came before a 10th Circuit panel after the district court denied Druley’s request for a preliminary injunction. Druley, representing herself, had obvious flaws in her complaint making it unlikely to succeed, but the biggest problem she faced was that a 1986 10th Circuit panel had ruled that transgender inmates have no constitutional right to receive hormone therapy.

Although 1986 is practically the Dark Ages regarding gender identity law, that panel decision has never been overruled and so only the Supreme Court or the full 10th Circuit, sitting en banc, can reverse it –– not a single three-judge panel.

On the question of whether the prison’s actions regarding hormone dosages amounted to cruel and unusual punishment forbidden under the Eighth Amendment –– because officials were “deliberately indifferent” to Druley’s serious medical condition –– Circuit Judge Jerome Holmes, writing for the panel that included Gorsuch, noted the plaintiff’s suggestion the prison should follow treatment levels suggested by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health but pointed out that those standards “are intended to provide flexible directions” and leave it up to individual professionals and organized programs to modify as particular cases require.

Druley asserted she had received no hormone therapy at all from 1988 until 2011, but she was not seeking damages for that deprivation, but instead an order that her dosage be increased.

On Druley’s effort to win the right to wear feminine underwear or be moved to a different building to alleviate an asthma condition, neither issue would typically raise Eighth Amendment concerns, and her 14th Amendment equal protection claims were defeated by existing 10th Circuit precedent that complaints of discrimination based on gender identity are not subject to heightened scrutiny. As long as the prison could demonstrate a rational purpose in its policy toward her, its actions would withstand her suit.

“Ms. Druley did not allege any facts suggesting the [prison’s] decision concerning her clothing or housing do not bear a rational relation to a legitimate state purpose,” Judge Holmes wrote.

Given the precedents binding on this panel in the Druley case, it is difficult to read much into this opinion, which Gorsuch signed but did not write, regarding his underlying view on transgender rights.

In another gender identity case, where Gorsuch was sitting as a guest judge in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, a transgender woman who was an instructor at Maricopa County Community College in Arizona was banned from using the women’s restroom after other females complained about a “man” in their restroom. Rebecca Kastl, who was presenting as female but had not undergone sex reassignment surgery, was denied renewal of her teaching contract after the complaints from the women. She filed sex discrimination claims under Title IX of the 1972 federal education statute and Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, but the district court dismissed the case on summary judgment in 2006.

In 2009, an unpublished “Memorandum” not attributed to any of the judges on the panel where Gorsuch sat acknowledged that a transgender person could pursue a discrimination claim under both Title VII and Title IX using a sex-stereotyping theory to bring it within the scope of sex discrimination protections. The panel concluded, however, that the college had “satisfied its burden” of justifying its actions by presenting evidence that “it banned Kastl from using the women’s restroom for safety reasons.”

At that point, she would have to show that this reason was merely a pretext for the college’s discriminatory intent, but the court found that she “did not put forward sufficient evidence demonstrating that MCCCD was motivated by Kastl’s gender.”

A footnote to the opinion, however, seemed to undermine the reasonableness of the panel’s conclusion: “We note that the parties do not appear to have considered any type of accommodation that would have permitted Kastl to use a restroom other than those dedicated to men. After all, Kastl identified and presented full-time as female, and she argued to [the college] that the men’s restroom was not only inappropriate for but also potentially dangerous to her.”

That language suggests some sensitivity to Kastl’s concerns, but not enough to cause the panel to reverse the district court.

This opinion, more than the prison ruling, might say something about Gorsuch’s opinions about discrimination claims by transgender plaintiffs.

Curiously, Kastl was represented by a Tucson attorney, Andrew Martin Jacobs, and Lambda Legal filed an amicus brief by F. Brian Chase in support of her appeal. Yet in Lambda’s review of Gorsuch’s record, posted on its website, the Kastl decision is not mentioned while the Druley one is.

The most important LGBT rights decisions by the 10th Circuit in recent years, its two rulings striking down bans on same-sex marriage in Utah and Oklahoma, were decided by three-judge panels that did not include Gorsuch. Nor was Gorsuch on the panel that decided Etsitty v. Utah Transit Authority, a 2007 decision that rejected the argument that gender identity was a “suspect classification” that would have qualified a transgender public employee’s equal protection claim for heightened judicial scrutiny.

Gorsuch, then, is not “on the record” directly on LGBTQ issues, but his overall record suggests that there are good grounds for the community to oppose his confirmation. He was part of the 10th Circuit en banc panel in the infamous Hobby Lobby case –– where the Supreme Court ultimately granted a privately-held company a religious exemption from complying with the Affordable Care Act’s contraception coverage requirement –– and signed on to a concurring opinion, containing language suggesting he would support broad religious exemptions from antidiscrimination laws.

Now pending before the Supreme Court is a petition to review a case from Gorsuch’s home state, Colorado, in which the state courts held that a baker violated the state’s public accommodations law by refusing on religious grounds to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. If that petition is granted (the court recently requested records from the Colorado courts for discussion at one of its remaining conferences, signaling interest in the case) and Gorsuch is quickly confirmed, it could be among the first cases argued after he takes his seat. (The court has scheduled arguments through the end of February, and it plans to conclude hearing arguments for this term in April.)

In an essay he published in 2005, Gorsuch expressed opposition to civil rights impact litigation, characterizing it as an attempt by liberal groups to advance their agenda through the courts rather than through the democratic process in legislatures. He left no doubt he would have rejected an attempt to get a court where he sat to order states to allow same-sex marriages, based on his view that such policy issues should not be decided in the courts. His views on this are consistent with those of the four Obergefell dissenting justices, Chief Justice John Roberts famously ending his dissent by writing that the majority’s decision had “nothing to do with the Constitution.”

Gorsuch has also never ruled in an abortion case, though he dissented from the 10th Circuit’s refusal to reconsider a panel ruling that a religiously-affiliated organization with religious objections to contraception methods it deemed a form of abortion could be required under the Affordable Care Act to notify the government of its objections so an alternative means for contraceptive coverage could be arranged. Gorsuch specifically endorsed the argument that the organization’s refusal to be complicit in any way with providing coverage –– even through such a minimal requirement as notifying the government that the organization itself would not provide it –– placed a substantial burden on the organization in violation of the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Gorsuch appears to place such heavy weight on an expansive reading of the Free Exercise Clause that it would not be much of a stretch to suggest he might be willing to overrule the Supreme Court’s decision in Employment Division v. Smith, an important 1990 case, in which Scalia wrote for the majority, holding that the First Amendment does not privilege people to violate neutral state laws of general application based on their religious beliefs. This ruling led to the enactment of the federal RFRA and subsequent state RFRA statutes, which are now at the heart of the contention that people with religious objections to same-sex marriage or gender transition should be excused from complying with anti-discrimination laws.

There is widespread speculation that the Trump administration may release an executive order allowing federal contractors and federal employees to discriminate in providing services and making employment decisions based on religious beliefs. Such an order would undoubtedly be challenged in litigation that could end up in the Supreme Court.

Gorsuch was unanimously confirmed by the Senate on a voice vote after his nomination to the 10th Circuit by President George W. Bush. He has all the credentials that suggest an easy confirmation: elite education (Columbia, Oxford, Harvard Law), federal clerkships (including the Supreme Court), practice in a big firm, service as a federal appeals judge, no scandal attached to his name, and a reputation as a collegial judge who writes in a clear, conversational style without the kind of hyperbole, venom, and sarcasm that Scalia employed in his dissenting opinions.

Gorsuch has been a frequent dissenter on the 10th Circuit, but his dissents are temperate and dispassionate in tone and closely reasoned, although they frequently rest on conservative premises that most progressives would instinctively reject.

He can’t be opposed as technically unqualified, but he can be characterized as far to the right of the judicial “mainstream,” justifying firm opposition by those concerned with LGBTQ rights, reproductive rights, and the ability to live in a civil society that does not countenance disadvantaging people because of the religious beliefs held by their employers or by legislators.