Reggie Wilson’s Holy Grail honors song, vocals, and movement

Reggie Wilson had us from the get go. Appealing to our penchant for the exotic, sweet, harmless folk tales to take us back to simpler times, his title “The Tale: Npinpee Nckutchie and the Tail of the Golden Dek” is a catch-all. If the name is an imaginative fabrication or has some basis in fable, it sounds sexual; Wilson says, “Its like the Holy Grail.”

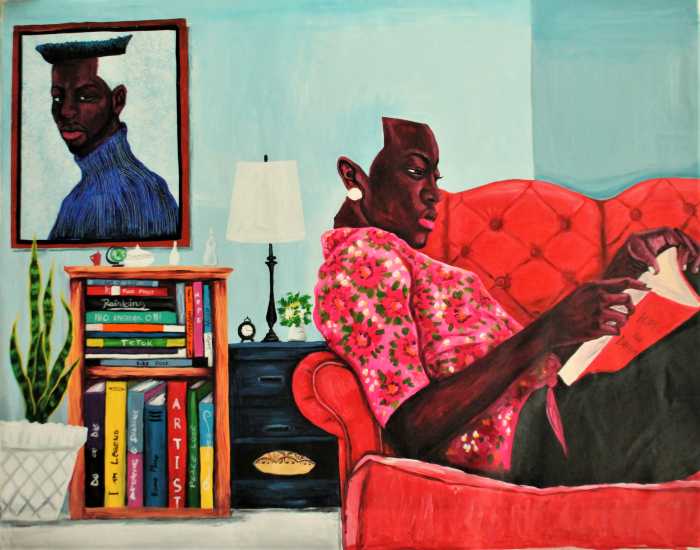

True to the name of his company, Fist & Heel Performance Group, Wilson explores traditions of black dance. The full evening piece is a seamless collage that places vocals and songs on equal footing with the movement. It’s an enjoyable lexicon sewn with threads of humanism. The performers are from Africa, Brooklyn, Trinidad , Tobago, Texas, and Jamaica.

Lawrence Harding, with F&HPG since ’94, is from Sierra Leone. He brings a popular highlife song about a chicken crowin.’ Vocalist Elaine Flowers and Harding get to keep their glasses on and “move around a bit,” is how Harding half-jokingly put it in the after-talk. Enjoying the full company dances has its rewards. The compromise necessary in creating Wilson’s inclusive group creates a refreshing dynamic—different than a Broadway chorus line where everyone can lift their leg to equal height together. Pro Paul Hamilton and Ivory Coast dancer Michel Kouakou are gorgeous movers, but we don’t see enough of their craft. In the end, we are treated to fine same-sex duets by dancers Penelope Kalloo and Pene McCourty and the admirable Hamilton and Kouakou. Kalloo and McCourty “push arms” as in gentle martial arts. The men, also in a fighting stance, push up and turn over each other with centrifugal force; the fascinating blur makes a circle of black on the floor.

Wilson once danced with Ohad Naharin but after injuring his knee he developed his music and choreography. Flowers, Harding, and Rhetta Aleong complete this group, the vocal element. There’s drama in Aleong’s joyful expression and McCourty’s ennui, even pain.

“I was always interested in movement with voice,” said McCourty afterward.” There’s a middle ground on the dance floor. On the concert stage, in common social dance moves, their deceptively easy openness releases us. As costume designer extraordinaire Naoko Nagata said with candor afterward to Wilson, “When I work with this company I sleep smiling.” Nagata began as a biochemist in Japan and now costumes the dance world.

The club set and lighting are by Jonathan Belcher; wings and backdrop are curtains of Mylar strips, accented with rows of yellow lights that flash out at us once or twice. The disco atmosphere is achieved with mood-altering colors that reflect on the curtains bathing the black clad, black and brown skinned dancers in the nightlife. On stage together, moving separately in unison, the dancers find common denominators like voluptuous pelvic rotations. They find intimate connection in spooning or in spawning formations. In a duet, Kouakou pumps Kalloo from behind like the Latin doggie.

Steppin’ is the couples’ dance from the Mississippi delta that Wilson saw in a Milwaukee nightclub on a recent visit to his hometown. That basic form, ring shout, call-and-response and hip hop in “The Tale…” evince The Great Migration. Like Ralph Lemon, Wilson traveled the world for material and inspiration and then found it in his own backyard. But while Lemon reenacts injustice in his “Geography,” Wilson recalls the experience through the mediation of vernacular dance and music, focusing now on couples.

On the right of the stage the vocalists are tight and together in fervent religious spirituals, “Where have you been when the first trumpet sounds?” and “Adam Hiding Again.” Meanwhile on the left, four dance wild and chaotic with equal passion. Both groups are spent. The wall between sacred and profane ecstasy dissolves and disappears while couples gyrate to “Get your fire’s” dancehall beat. “My soul says yes, yes, yes.”

gaycitynews.com